Due to the impact of climate change, rising sea levels, increased rainfall and flooding are becoming a day to-day reality for people in Lagos. The proposal embraces this inevitable future. Envisioning a new form of urbanism that enhances a symbiotic relationship between man and water.

Adopting the monopile construction system that is utilised in offshore wind farms as a deliberate choice in stark opposition to the typically used floating technique, which has a short life span and often fails after heavy rains. The sturdy nature of the pile provides a secure and solid base for communities to flourish, free from flooding.

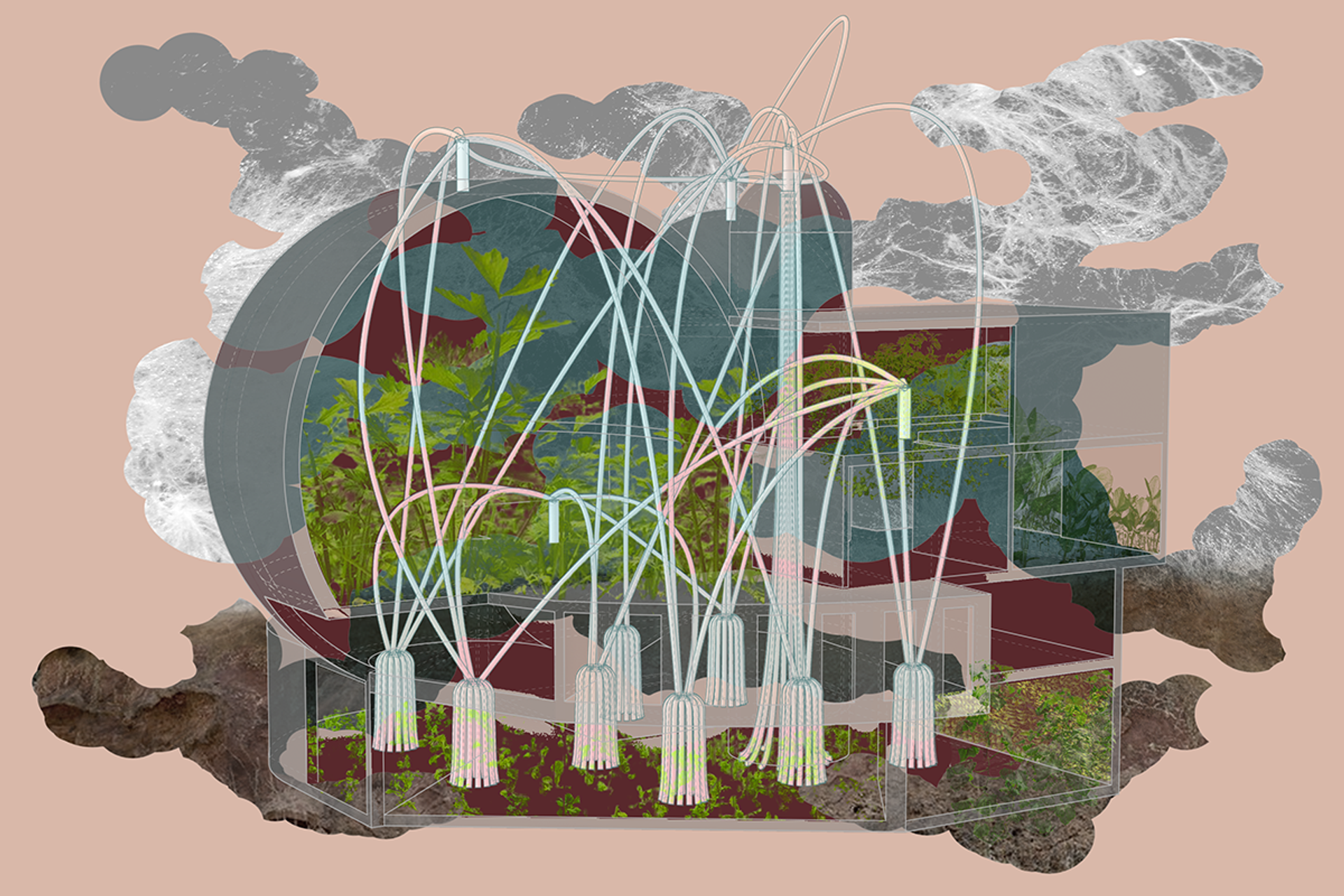

Each community cluster is supported by Service Platforms, Biorefineries and Market/Sports fields. The Clusters grow organically over time, adapting to the ever increasing demand for housing in Lagos. Each home is envisioned as an enclosed loop, in which the circular economy and metabolism of the home is of primary importance.

Water

Interspersed between the clusters are rooftop water harvesting farms. Capable of capturing enough water to supply 3 household water demands.

Food

The major source of food is the Rooftop farm, 60m2 of highly arable land with uninterrupted daylight hours. An integrated Aquaponics system built into the floating platform, produces up to 65% of the daily protein needs of the family.

Structure

The Flooring and structure are made from locally sourced and durable Eki wood (Lophira Alata) Walls and furniture are similarly made with local Akun (Uapaca Huedelotii). The modular nature of the design allows for each unit to grow and adapt as the family does.

Waste

Brown water waste is diverted to the Biodigester in the Floating Platform. This produces enough Methane to supply the family with constant cooking gas.

Energy

The main source of energy comes from the interspersed Wind-generators. Capable of supplying 5 households. The proposal is completely self sufficient will produce enough wind energy to support the majority of Lagos’s energy requirements.

"Water No Get Enemy" is the international Winner of the Lagos City of Water competition.

KOOZ What prompted you to partake within the International Lagos City of Water Competition?

LM For the past two years I have been living and working in Nigeria, where I helped set up and have been lecturing at the Architecture department in the University of Ibadan. During which I have been conducting research/working with the Great Demas Nwoko. A brilliant Architect/Artist.

The competition was a love letter to that experience and an incredible opportunity for me to explore the invaluable lessons I learnt from my time in Nigeria and lessons learnt from my mentor Demas Nwoko, whom set up spaces such as the New Culture Studio and Mbari club, both pivotal elements of the post colonial Nigerian creative movement. Giving rise to the likes of Wole Soyinka and Fela Kuti.

KOOZ What questions does the project raise and which does it address?

LM The proposal does not criticize the current political and urban planning that lead to the severe flooding in Lagos or the dire situation of the infamous Makoko floating village, it instead accepts the reality that leads to this environment and embraces the opportunities of this inevitable water based future. Challenging the way in which us as architects and urbanists tackle such an issue in a more positive and opportunistic manner.

All too often with these types of international “African” competitions, the entries come out with a myriad of stereotypes that are a copy and paste of an enforced idea of ‘African’ architecture. So in order to subvert this common trend I chose to challenge the way in which I designed the structures and urban flows, drawing heavily from the local cultural and ecological context. Revealing to my students how a different conceptual approach to a brief might manifest itself.

Each home is envisioned as an enclosed loop, in which the circular economy and metabolism of the home is of primary importance.

KOOZ What informed the approach to the design brief outlined?

LM Using the enigmatic work of the musician Fela Kuti as inspiration I named the project “Water No Get Enemy” after Felas’ classic 1975 hit which explains the salience of water. It mentions the obvious needs -washing, cooking, bathing, the raising of a child, etc. This brief summary introduces a reminiscent view on your use of water and its completely indispensable nature to our lives. In this highly politically charged song, Fela also suggests that, if the Nigerian political opposition work with nature, their ultimate victory is assured. Fela also sought to spur Africans to get back in touch with their powerful traditions and ways of being. And having seen the influences my students are drawing from, this sentiment is still desperately needed. The globalising homogeneity of the current design sphere is eliminating the uniqueness and opportunities that arise from a truly grounded cultural and ecological context. The proposal, much like the song, can be seen as an attempt to educate people on the beauty and opportunities of designing with communities and nature at its core, embracing a symbiotic relationship with the naturally occurring ecosystems. Enhancing and developing new streams of urban and ecological flows.

KOOZ What case studies and/or articles/readings informed your project?

LM The project draws heavily from my personal experiences into the field of Urban Metabolism research, conducted at the office of FABRICations in the Netherlands. Collaborative work with the brilliant Studio 8FOLD, an innovative design, strategy and research led studio based in London & Berlin. The work of the aforementioned Demas Nwoko, and time spent researching traditional Nigerian architecture. Research based thinking I picked up whilst studying at the extremely forward thinking London School of Architecture.

Obvious reference can be drawn to the works of Studio Precht in both the physical and conceptual realisation of the project. Literature such as: New Geographies 6: Grounding Metabolism, Daniel Ibañez and Nikos Katsikis; Understanding Urban Metabolism: A Tool For Urban Planning, Nektarios Chrysoulakis, Eduardo Anselmo De Castro, Eddy J Moors; Urban Metabolism Rotterdam: FABRICations 2014.

The globalising homogeneity of the current design sphere is eliminating the uniqueness and opportunities that arise from a truly grounded cultural and ecological context.

KOOZ Today the building and construction are responsible for 39% of all carbon emissions in the world, how, in your opinion, can we build better?

LM Today sustainability permeates through every aspect of the architectural profession. Yet I believe we need to go beyond the concept of sustainability, towards a form of regenerative architecture. We should seek to do more than just “sustain” our current built environment trajectory, we need to construct buildings that have a net-positive impact on the environment, economy and society.

Architecture should strive to create buildings that clean the environment, whilst embracing new streams that improve the labor, economic and social conditions, whilst catalysing lifestyle improvements such as food and water security, disaster prevention and mental health issues.

Employ local

Promote up-skilling

Use local, carbon-sequestering materials.

Engage local communities

Open source sharing of housing data and products.

KOOZ How and to what extent do you think that Architecture and Architect’s could and should play an active role within the contemporary climate crisis?

LM By thinking in terms of a regenerative architecture and applying larger conceptual ideas such as Urban Metabolism, the architect can attain a better understanding of urban casualties and metabolic flows, in order to create a truly regenerative urban realm. Which in turn will help combat the current climate crisis. However, in practice, the market driven forces that control the built environment are often beyond the control of the architect. Architects have lost so much control over the end result of a built project that we have little to no say as to how “sustainable” the project should/could be.

So I believe the best way in which we can enact actual change is through ideas and narratives. Competitions such as Voen Foundations’ “Lagos, City of Water” allows us architects to conceptualize and visualise what this alternative reality might be and through that vision and narrative we might affect actual change in the heart and minds of others.

I believe we need to go beyond the concept of sustainability, towards a form of regenerative architecture.

KOOZ What is for you the power of the Architectural imagination?

LM An Architect’s imagination helps to shape and create a physical manifestation of a culture’s societal values. This imagination introduces new aesthetic experiences to our daily activities all whilst challenging the preconceived notions of traditional forms of habitation. Architecture has an incredible power to produce collective meaning and shared memories in its complex relationship to the societal, environmental and historical contexts. It is the ultimate expression of a culture’s complex aspirations and should be seen as a valuable tool to help steer society towards a holistic future.

“Live in harmony with nature, and you will live longer and wiser. Be as inevitable and indispensable as water, because water….. WATER NO GET ENEMY” – Fela Kuti

KOOZ What is for you the architect’s most important tool?

LM Lateral thinking – The ability to challenge the way in which we have chosen to inhabit this planet, solving the problems that arise in a unique and “out of the box” manner.

A little bit of computer program skills never hurt either…

Bio

Lloyd was born in Zimbabwe, raised in Botswana, trained in South Africa and spent upwards of eight years travelling. He is driven by new experiences in his creative and social realms; feeding off the unknown and with hunger for knowledge and adventure. He is on a constant quest for new creative solutions to the complex issues of the built environment, and believes in an honest architecture that can critically engage with its environmental, political and social environment. For the past two years he helped set up and has been lecturing at the Architecture department in the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Lloyd also heads up the competition team at studio 8FOLD.