Let's imagine a stadium. In the centre, a green field, and around it, an Olympic track, four hundred metres of tartan. On it, 45 runners, each holding a baton in their hand. But beware, the baton is not a carefully designed piece of plastic or fibreglass with the event's logo on it. It is a piece of paper with a written manifesto. Quoting Beatriz Colomina, "the manifesto is media, it does not exist outside of paper."1

If the 45 participants were to start running at the same time, the International Manifesto Relay (IMR), organised by Copenhagen Architecture Festival (CAFx), would turn into a stampede rather than a relay race.

If the 45 participants were to start running at the same time, the International Manifesto Relay (IMR), organised by Copenhagen Architecture Festival (CAFx), would turn into a stampede rather than a relay race. It would be a stampede full of strength, energy, ideas to spread, experiments to propose and actions to take, yes, but a stampede nonetheless, with a lot of noise and commotion, with the risk of getting lost in the abyss of misunderstanding.

Sustainable futures - Leave no one behind is the theme of the UIA Congress 2023 that the IMR aims to respond to. Based on this theme, 45 spatial researchers and practitioners were invited to reflect on the six congress topics: Climate Adaptation, Rethinking Resources, Resilient Communities, Health, Inclusivity, and Partnerships for Change. Six research panels, which we could compare to six lanes on the track. And yet, after reading and examining the 45 manifestos, there is no doubt that the most powerful ones are those that manage to integrate, directly or tangentially, all six topics at once.

Because, let's think about it: aren't they six faces on the same dice?

The first iteration of the Manifesto Relay spoke to a national audience. Bound to the Danish context, the 2019 MR used the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus as an opportunity to reflect on the legacy of the school, particularly its transdisciplinary approach and its utopian vision. "The process of collecting manifestos in 2019 was a sort of dream machine," the curatorial team at CAFx expressed in an interview with KoozArch.

The 2023 IMR is based on the urgency to deconstruct—if not to eliminate—the blind spots with which our profession has had to struggle over the past twenty or thirty years.

Apart from its international stance, which is already an important difference from its 2019 counterpart, the 2023 IMR is based on the urgency to deconstruct—if not to eliminate—the blind spots with which our profession, perhaps influenced by those very same 20th-century utopias and modernist schools, has had to struggle over the past twenty or thirty years. And all of this, with a full awareness of the immediacy imposed by the ecological and sociopolitical crisis that we have exacerbated and have no choice but to confront.

In this way, the Manifesto for a happy and creative frugality, by Dominique Gauzin-Müller, Alain Bornarel, and Philippe Madec, takes the lead and asks, point black: To build or not to build?

The question could seem counterintuitive when asked by architects, the very same professionals who make a living by designing and erecting buildings. And yet it appears, reframed with different vocabulary and disparate intentions, throughout several of the 45 manifestos.

A direct response to the well-worn modernist motto, frugality as a manifesto is in itself a form of ecology, a way of thinking that emerges from the ground, far away from technocratic positions.

To answer it, Gauzin-Müller and co. suggest frugality as an ethical ambition to connect resources, community and place. “Form ever follows frugality”. A direct response to the well-worn modernist motto, frugality as a manifesto is in itself a form of ecology, a way of thinking that emerges from the ground, far away from technocratic positions, looking at the specificities of every environment in order to find truly inclusive avenues, daring “to act outside the law to advance the law.”

The frugal manifesto still chooses the first option, outlining vague ideas to do it in a better way.

A hundred metres later, continuing the critical offensive on the modernist foundations that still function as pillars of our profession, and playfully winking at them, Jonathan Houser proposes Towards an Oceanic Architecture. The phrase "towards a..." followed by an infinite number of possibilities has become commonplace. Nevertheless—we don’t know how, or why—it still sounds appealing for us architects. As evidence, three of the 45 manifestos are named with the prefix "Towards..."

In an undeniably powerful image, Houser takes the famous spread of Le Corbusier’s Towards an Architecture—the one where the ruins of the Parthenon are contrasted against profile pictures of newly constructed, sexy convertible automobiles—and crosses it with a big red X. Below, Hauser positions the same Parthenon pictures and compares them with a close-up image of the sea and the portrait of a butterfly—last observed in Denmark in 1976— “whose metamorphosis can be interpreted as a metaphorical promise of a future where the man-made environment can rise from the ashes of the 20th Century—a hopeful promise with architecture as the messenger!”

“What spaces would arise if it was nature’s scale and its processes, not its image, we tried to translate into architecture?” - Jonathan Houser, Towards an Oceanic Architecture

Should the agency of architecture be limited to transmit assurance of a better future?

“What spaces would arise if it was nature’s scale and its processes, not its image, we tried to translate into architecture?” Beyond its powerful visual composition, the premise of oceanic architecture lies in this central idea: architecture cannot continue to perceive itself as a human-made isolated object, but rather as a complex project in dire need of re-discovering the ties it holds with its environment—social, political and ecological.

More than a messenger, architecture needs to be the message itself.

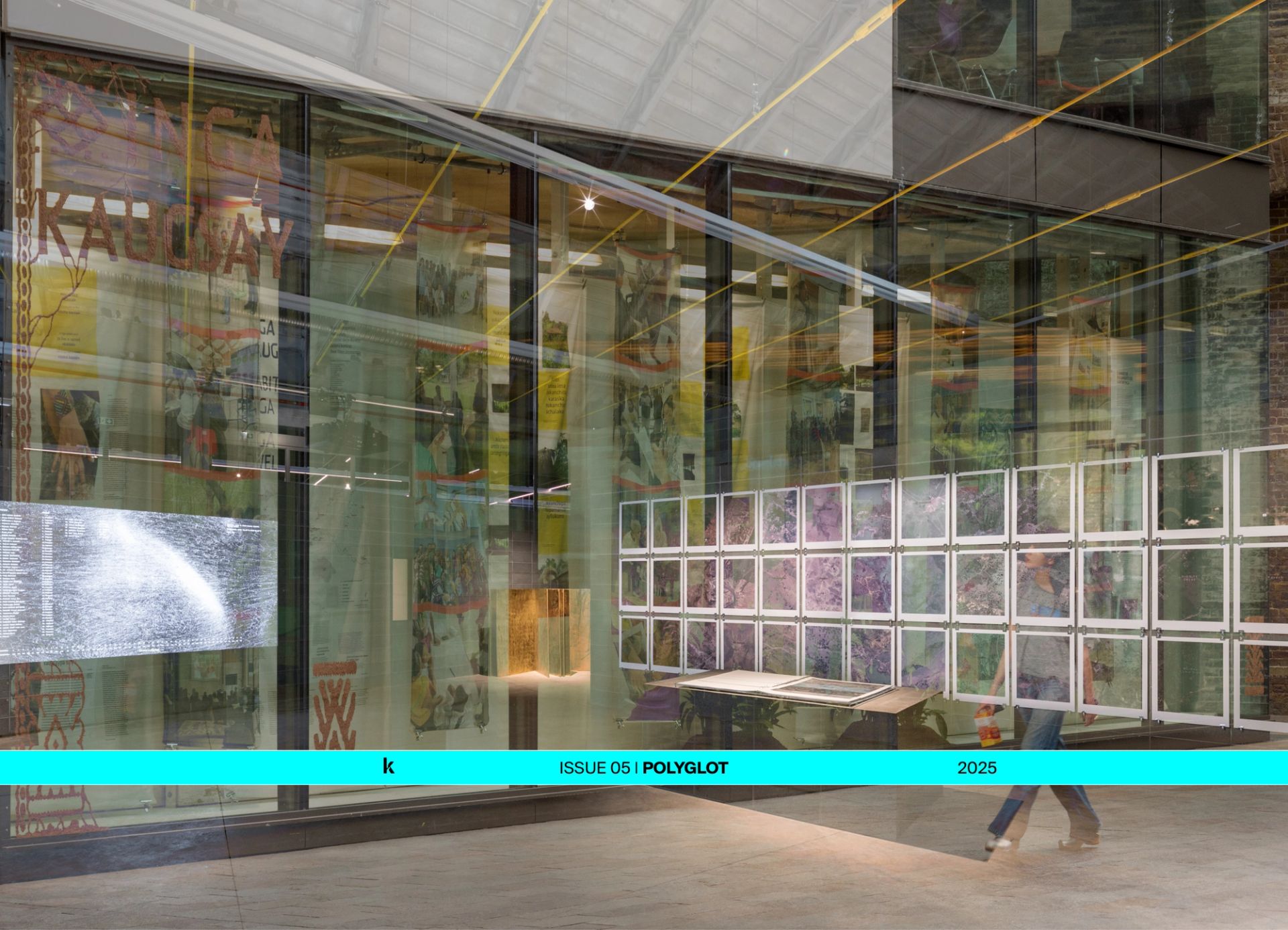

Towards Oceanic Architecture passes the baton to Towards an Indigenous Guardianship of Resources. Focusing on forests, this manifesto envisions a system to mitigate issues of deforestation by empowering local indigenous communities. Around the world, these communities possess—and have always done so—the necessary knowledge to reset the relationship between humans and land, transforming it from purely extractive to intrinsically symbiotic. After having failed (more than once), architects are finally stripping off their modern suits. They are ready to pause, look back, and listen to the long-forgotten voices that modernism silenced for decades. The only question now would be: why wait until 2050?

Architects are finally stripping off their modern suits. They are ready to pause, look back, and listen to the long-forgotten voices that modernism silenced for decades. The only question now would be: why wait until 2050?

Furthermore, the Indigenous Guardianship of Resources selects keywords—such as ancestry, coexistence, ownership, guardianship and empowerment—and renders them in a bilingual manner as part of a Glossary of Agency. A big reminder: the agency of architecture should also engage language. Architecture is not only about graphic representation and drawings. Space is also about vocabulary. Architects and their manifestos ought to pay careful attention to existing buzz words which frequently get misused, or at least misinterpreted throughout the field. Recently published, architect, verb (Verso Books, 2023) by Reiner de Graaf, approaches the topic by investigating common architecture-related terms —world class, excellence, sustainability, wellbeing, liveability, placemaking, creativity and beauty—unpacking their implications in relation to current and future architectural practice.

Could we think of the architect as a kind of visually equipped linguist? In order to change the built environment we need to change our ideas, and in order to change our ideas, we need to change the words we use to describe them.

A glossary of the 45 manifestos could include definitions for growth, bottom-up, circular, disaster, climate change, digital world, collaborative, inclusivity, transdisciplinary and a long etcétera. Words that appear over and over throughout the international relay and that can mean different things for different people. Could we think of the architect as a kind of visually equipped linguist? In order to change the built environment we need to change our ideas, and in order to change our ideas, we need to change the words we use to describe them.

The great majority of the 45 manifestos concerned themselves, in one way or another with the climate crisis, local empowerment and with strategies to address gender and race inequality in the built environment. All look unto the future. And what future is there without technology? What world is there without virtual reality and virtual world making?

the Meta-festo is a call for architects to understand digital tools not as a solution, nor as a magical panacea to confront physical challenges, but rather as anticipatory instruments to inform design and decision making processes.

More than treating the metaverse as an escape for the perils of reality, or as a purely ludic and hedonistic space where new, yet-to-be-defined policy and law may apply, Meta-festo, by Qhawarizmi Norhisham, puts forward the concept of the Digital Twin. “Powered by a gaming engine, the digital twin environment is attuned to the forces of nature and the logic that buildings and structures endure in real life [to] find the most vulnerable point of failure for maintenance work. This information is crucial to avoid any downtime and mitigate possible risks.” In this way, the Meta-festo is a call for architects to understand digital tools not as a solution, nor as a magical panacea to confront physical challenges, but rather as anticipatory instruments to inform design and decision making processes.

Beatriz Colomina, in her Manifesto Architecture, assures that “Every manifesto reworks previous manifestos”, and that “Design is part of the manifesto”. Some of the 45 contributions for this year already took a step forward and incorporated a project to ground their vision. Others stood on the shoulders of previous manifestos, either to build up on them or to deconstruct and rephrase what they perceived to be flawed.

On its first world-wide edition, the IMR has demonstrated to be a remarkable platform for architects worldwide to declare their principles, aims, and aspirations.

On its first world-wide edition, the IMR has demonstrated to be a remarkable platform for architects worldwide to declare their principles, aims, and aspirations. As Martha Thorne's preface reminds us, the power of the manifesto lies on its ability to extend beyond their predefined audience and reach the larger public realm, inviting evaluation and potential criticism of the status quo. The 45 manifestos reflect the collective awareness of the challenges we face and the urgent need for action. They serve as a dynamic exchange of ideas with transformative potential, advocating for a redefined role of architecture in society. Their bottomline could very well read: architects of the 21st century, let’s embrace new positions, challenge established norms and push the boundaries of the profession.

Finally, the 45 manifestos created for the IMR 2023 cannot get lost on the digital archive of the CAFx website. The next International Manifesto Relay cannot start from scratch. Let us take the UIA 2023 Congress as an opportunity to build up on our determination. Let us embrace this collective call and tie it to future, more concise and immediate proposals for change. Let us go beyond utopia. Let’s continue to run.

Bio

Enrique Aureng Silva is chief editor at KoozArch. He is an architect and a writer with interests in architectural history, storytelling, literature and translation. His research is focused on the critical conservation of architectural heritage, exploring the impact that historic narratives have on the present and future of our built environment. His current work intends to think about preservation theory and practice beyond material means. He received his BArch from National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), a Master of Design Studies at Harvard and a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing at NYU. He has collaborated with several architecture offices in Mexico and the United States and has been a research fellow at Harvard and New York University. Parallel to his work at KoozArch, he is founder of versiones.press, a literary translation journal.

Notes

1 Colomina, Beatriz., Nikolaus Hirsch, and Markus Miessen. 2014. Manifesto Architecture : the Ghost of Mies. Berlin: Sternberg.

Bibliography

Beatriz Colomina, Nikolaus Hirsch, and Markus Miessen, Manifesto Architecture : the Ghost of Mies. (Berlin: Sternberg, 2014).

Reinier De Graaf, architect, verb.: The New Language of Building. (London: Verso Books, 2023).