What if new planetary relationships begin with a new vocabulary?

What we do as architectural workers and thinkers is not separate from the contexts in which it is done. In order to learn across contexts — to permeate barriers enclosing modes of understanding — architecture must embrace a multiplicity of words, spoken, written, existing and yet to be coined. To quote historian and theorist Samia Henni, “The processes of historicising built environments from around the world are contingent on the sources that scholars draw upon and on the languages that they speak.” From architect as ‘chief builder’ (derived from French, Latin and Greek) to the umqambi wesino1 — from the Zulu term transliterating as space magician — our roles are myriad and agencies many, reflected in a multifaceted lexicon. Now more than ever, it’s vital to bring oneself, in one’s own words, to the table. Polyglot is a quest to grow the vocabulary we need to expand the diverse potentials of spatial practice.

Now more than ever, it’s vital to bring oneself, in one’s own words, to the table. Polyglot is a quest to grow the vocabulary we need to expand the diverse potentials of spatial practice.

Ask Oscar Wilde: language is and has ever been a social barrier. The value of its agency has been demonstrated throughout history by such social pioneers as Frederick Douglass and Mahatma Gandhi. Only through the mastery of the English language were they able to make their respective case for emancipation from slavery and oppression — which reap their vicious rewards regardless of the vocabulary used to justify the extractive scars left on land and people.

Of course, the question of language is inherently spatial, political, even geographical. Such is its power to shape a societal and cultural identity, language has often been instrumental in drawing barriers between entire nation states; time and again, the shadow lines of devolution crystallise based on major languages spoken, among the many other factors which signify kinship and mutual understanding. Maps are overwritten with new, ‘revised’ place names, replacing those given by ancient, rooted myths and indigenous folklore; as a result, we lose deep-seated connections with space, landscape, climate, material and cultural realities that were embedded in local, latterly defunct languages.

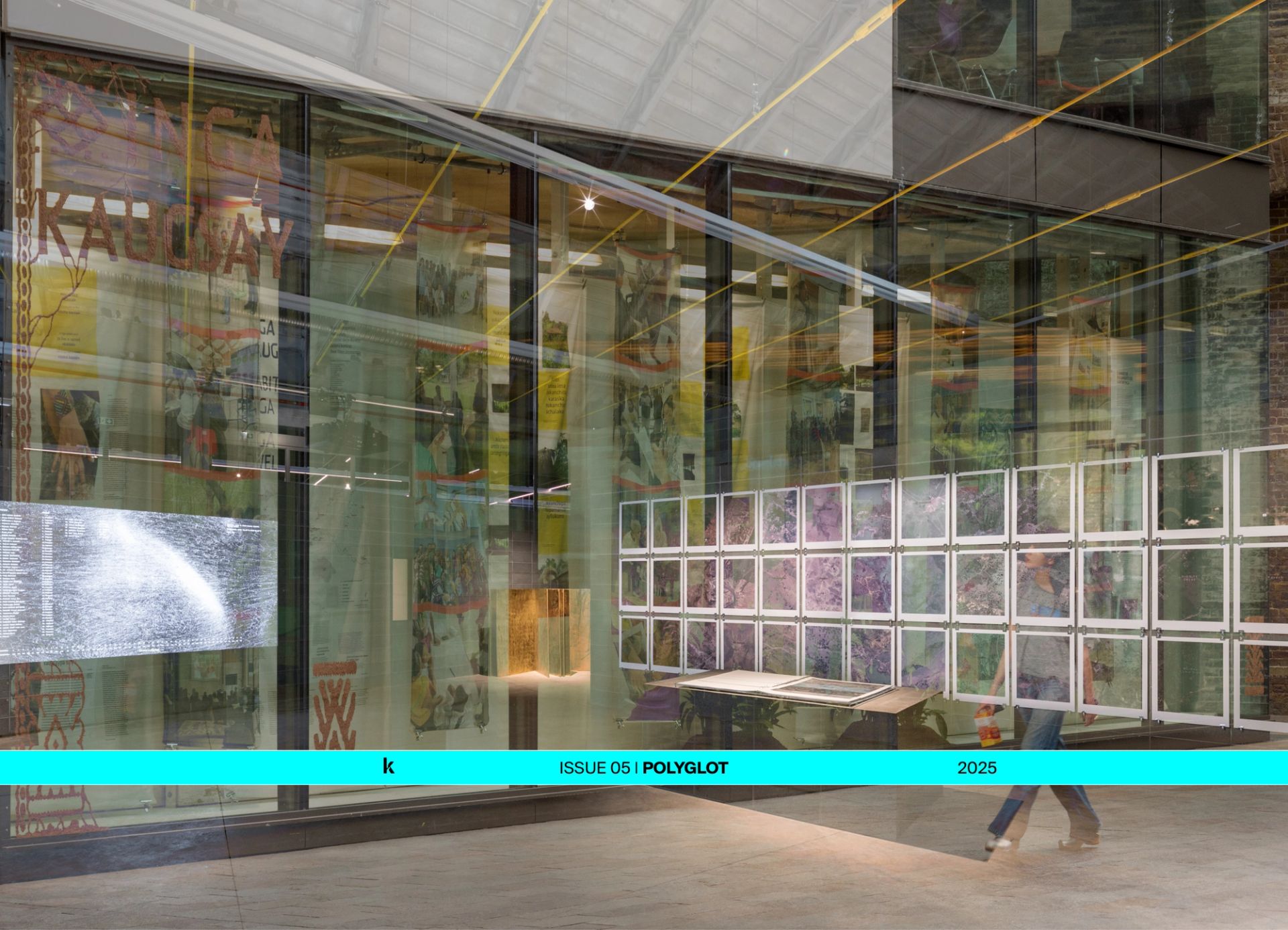

Slavs and Tatars, Mother Tongues and Father Throats, 2012, woolen yarn, ca. 500×300 cm.

The connection between language or languages, and architecture has a biblical model or precedent in the story of the Tower of Babel. Man’s attempt to reach the realm and greatness of the gods through the construction of a magnificent edifice was foiled by divine intervention of linguistic kind. According to the Good Book, people suddenly lost the ability to communicate with each other and as a common lingua franca — miraculously, if the story is to be believed — transformed into dozens upon dozens of irreconcilable dialects, thus thwarting the possibility for reaching any common goal,

Parallels between the designed ordering of space and the structural order of language have been pointed out more than once, through various theoretical lenses. Grammar, syntax — even the much-abused ‘vernacular’ — all these words are commonly used to describe styles and tectonics within architecture. Such terms feature in the study of both language and buildings, which would suggest that a variation in linguistic syntax and expression would produce a corresponding variation in architectural tectonics and style.

Unique powers are marshalled by individual vernaculars — be they ethnic, regional, technical or even martial. Dialects and argots form and define social enclaves; things get tribal. You’re either able to use the lexicon of the pack authentically — or you’re an impostor. As pointed out at the last Sharjah Architecture Triennial by Lagos-based practitioner Papa Omotayo, the obligation to not only speak but also think in English created a sense of otherness during his studies in the UK.

Dialects and argots form and define social enclaves; things get tribal. You’re either able to use the lexicon of the pack authentically — or you’re an impostor.

How, then, does one explain the universal uptick in the popularity of apps like Duolingo, Babbel, Memrise, even Google Translate? Particularly since the pandemic, there has been a pronounced rise in the desire to learn languages other than our own. Perhaps being confined to our homes exacerbated our desire to connect across space, leading us to loosen our tongues and find more ways to communicate. Through a focus on how we read, write and speak, the Polyglot issue aims to recognise embedded intelligence, even as it stokes more dialogue between a polyphony of diverse readers, both in and outside of architectural practice. Through this issue, KoozArch hopes to build a framework for greater accessibility and empathy.

Polyglot challenges the progressive colonisation of the architectural language, embracing local nuances, informal vernaculars and regional dialects to evidence alternative approaches to the making and perception of our built environment. This issue collects a series of contributions from recognised and emerging thinkers, practitioners, designers and artists who orient themselves around spatial and architectural agency. Polyglot maintains and depends on a spectrum of voices, not limited to their linguistic and ethnographic scope but also in terms of discipline, position and neurodiversity.

Such an attempt could never hope to be exhaustive or definitive, as language and its modes of operation are in states of constant flux. The full scope of Polyglot might be realised only if we could produce alternative or translated iterations, across multiple publishing formats. Yet, as a collection of published contributions, Polyglot would celebrate special attention to those forms of articulation which would seem to be unseen or under threat; languages shared by dwindling numbers of speakers, forbidden or unrecognised dialects, words and phrases which stand only in poetry, song, in the names of places or the inflections of their physical forms.

Polyglot challenges the progressive colonisation of the architectural language, embracing local nuances, informal vernaculars and regional dialects to evidence alternative approaches to the making and perception of our built environment.

The study of past attempts to define architectural glossaries reveal the fluctuation of various concerns in disciplinary discourse; words go in and out of fashion. In this issue, architectural educators Thomas Aquilina and Mpho Matsipa discuss their ongoing attempts to define a glossary for spatial justice, adding another chapter to the history of architectural glossaries that have been published for centuries.

The collective of designers, thinkers and writers that constitute Rural Futurisms tell us about their understanding of Tswana spatiality, developed through working in Makgobistad, South Africa, and their dialogue with the cosmology of its dwellers. From the curators of SALT Galata, ‘Translated into Socialism’ explores how the Turkish-speaking communities in Yugoslavia affirmed and transformed their identity under socialist ideology. Exploring the critical possibilities of translation, we share extracts from Roberta Marcaccio’s recent translation of the works of Ernesto Nathan Rogers. Rogers — who had a passing grasp of English, due in part to his British heritage — stuck expressing himself in his native Italian. When rendering one form of expression into another idiom, slippages in meaning are inevitable, sometimes transforming the impact of particular phrases and concepts irrevocably. Kiel Moe describes the slippages and modulations across disciplinary codes and jargons, testing the limits of intercommunication.

Elsewhere, Brazilian architectural scholar Paulo Tavares elects to speak with the celebrated indigenous activist, thinker and writer Ailton Krenak, on the situated perspectives and insights of indigenous peoples: which vocabularies are under threat and which ones might help us to survive the planetary polycrises? Writing from Sri Lanka, Sharmini Pereira describes the political complexity of language in a country where the sanguine struggles for sovereignty, land rights and freedom are ongoing; running a cultural institution in this context requires great sensitivity in the use of language, carefully balanced in order that all feel welcome. Maite Borjabad explores the concept of "otherness" — codified in the institutional format of the museum caption — as intertwined with systems of power and the politics of identity, while Manolis Stavrakakis unlocks insights from years of looking into the lost language known as Linear B.

These are but a few among the many articulations that make up the Polyglot issue. Of course, each reader brings their own sensibilities — their own vernaculars, inflections and accents — to the table, meaning that nobody will read these contributions in exactly the same way. We each have the capacity for individual expression, but just as architecture is the work of many hands, so too is its discourse made up of many tongues. We hope you enjoy the reflections that make up this issue, ultimately adding your own voice to the conversation wherever you are.

Notes

1 See Lesley Lokko, ‘African Space Magicians: an excerpt’, published on Reading Design https://www.readingdesign.org/african-space-magicians (accessed 14 Jan 2025) Originally published in … And Other Such Stories (Chicago Architecture Biennial in association with Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2019)