Abstract

Our research frames the worlds of popular videogames in a new light by looking at them in relation to buildings, places and cities from the real world. Inspired by the way architects make surveys and mappings to analyse cities and understand how their form and function came to be, we combine both drawings and writing together to examine what makes these virtual worlds so unique. In doing so, we demonstrate that many of the principles key to the design and experience of these modern game worlds connect to architectural ideas and concepts that are often hundreds of years old. In turn this reinforces the value of game worlds as architectural sites in their own right, with their own spatial innovations and design histories, that challenge what it means to realise, or construct, a piece of architecture today.

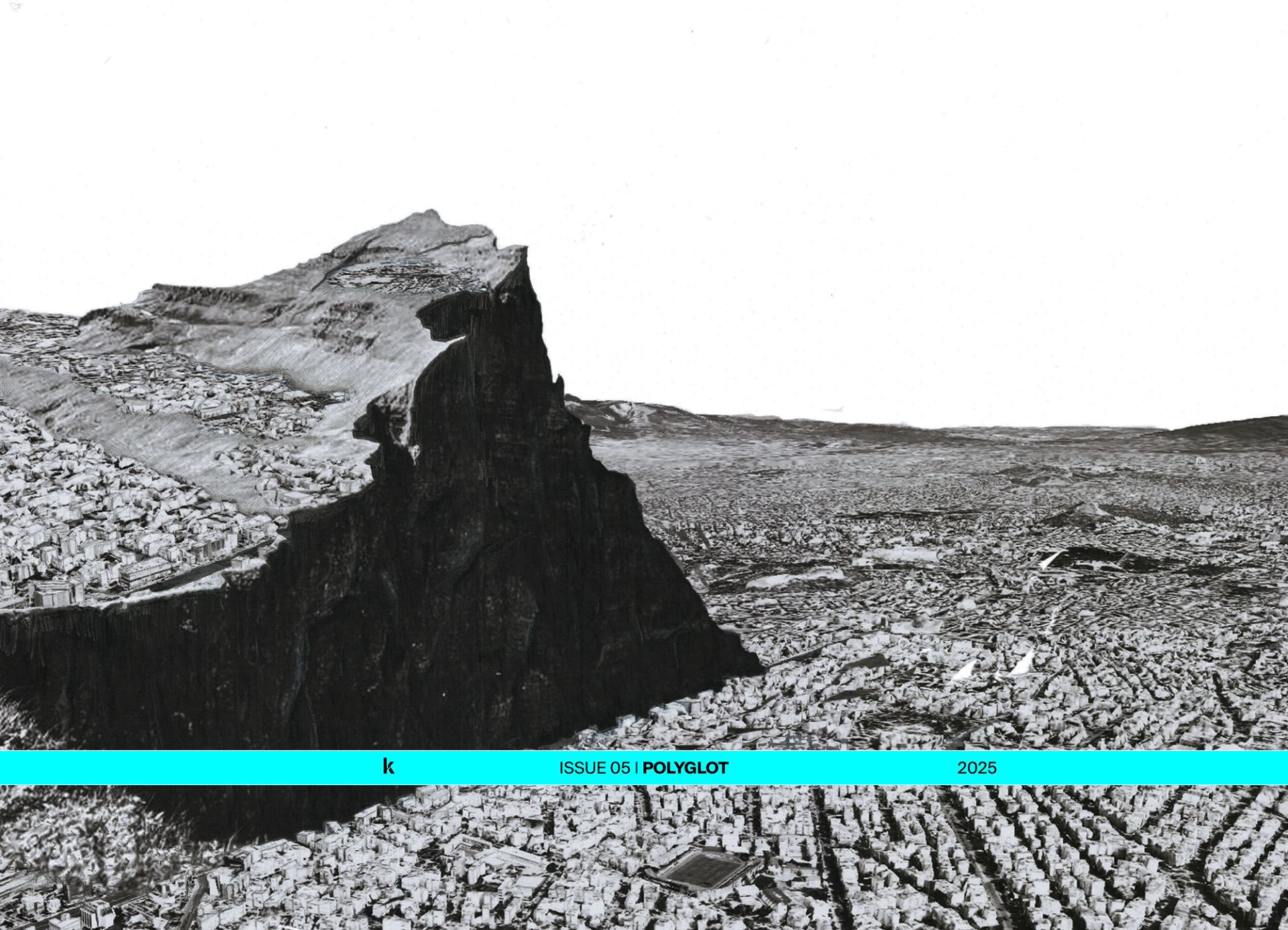

Every day millions of people travel to strange and wonderful worlds full of puzzles and adventure – where they can undertake grand battles and assume new identities to experience stories that unfold around them. They participate in simulated societies while also belonging to collective spaces that create new social structures. These are the worlds of videogames, synthetic environments that challenge our conception of space and how we interact with it. The aesthetic experience of videogames is immersive yet fragmentary, often seemingly illogical. We might die thousands of times but also feel at home there. This is precisely what attracts players to these virtual places and gives videogame worlds their power to move people. Jesper Juul calls these worlds “half-real”,1 where fictional stories meet stringent rules. While 2D games closely connect to techniques of architectural drawing, like the carved cross-sections of Lemmings (1991) or Shigeru Miyamoto’s Super Mario (1985) level designs, the advent of 3D games in the 1990s closed the distance between virtual space and real-world architecture. This was a time when Mario’s movement was liberated in Super Mario 64 (Nintendo, 1996), and the world opened to us in unforeseen new ways. We knew New York or Hong Kong by playing Deus Ex (Ion Storm, 2000), and we could experience a Mexican film noir through the vivid visuals of Grim Fandango’s Land of the Dead (LucasArts, 1998). Each of these games has its own method of evoking space for us to explore and dream within.

The aesthetic experience of videogames is immersive yet fragmentary, often seemingly illogical. We might die thousands of times but also feel at home there.

There are many possible, productive, relationships between videogame and architecture industries. With so much data organizing our contemporary lives, games offer a unique model for breaking down complex systems through storytelling. At the same time, architecture and its history enable game designers to understand how cities and spaces came to be. This can help to create more potent and credible worlds, from vernacular architecture or nifty wayfinding techniques, to accurately crafted façade details. This exchange of information is blurring the boundaries of what belongs to the physical or the virtual world. Certain aspects of architecture are challenged by the rising prevalence of videogames, making them ideal settings for the act of speculation. Architects have always imagined new worlds and societies, producing “paper architecture” projects that conjured up alternative visions for humanity. Italian architect Giovanni Battista Piranesi would create strange, paradoxical prisons with impossible geometry. The Metabolist group of architects from Japan proposed cities as giant organisms, and designed house-size robots. Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez made models of fantastical cities looking at the future of African urbanism, and Madelon Vriesendorp imagined buildings as characters, painting the Empire State and Chrysler buildings in bed together.2 Most videogames foreground fantastical environments because they are entertainment media designed to draw players into imagined and novel systems. In doing so, games re-establish the importance of utopian architecture that was used to hold a mirror up to society. Our research seeks to uncover how those fantasies are facilitated, and what games might be telling us about their architecture and society.

Most videogames foreground fantastical environments because they are designed to draw players into imagined and novel systems. In doing so, games re-establish the importance of utopian architecture that was used to hold a mirror up to society.

Through both visual and written analysis of game worlds our research explores their unique environments by developing a cartographic understanding of the spaces they allow us to play in. Game worlds are entirely synthetic – everything is made from scratch, with the developers deciding on the world’s edges and limitations and determining what aspects from reality will be simulated. This makes them extraordinary sites for evaluation, as each game holds its own idiosyncratic logic to be exposed. Our processes of mapping such worlds follows Mark Monmonier’s argument that “a map must offer a selective, incomplete view of reality”.3 In this way, we are interested in how very specific, focussed maps may illuminate different aspects of game worlds, highlighting the unique ways in which they deal with space. Even accounting for the tropes of genre, viewpoint or similarities in code (such as the use of specific game engine platforms), every game offers a divergent and synthetic viewpoint of the world, requiring different types of drawn analysis to understand it.

Alongside the “physical” qualities of the game worlds, the presence of players also defines their urbanism, creating social spaces for people to inhabit. These spaces can exist both within the game and through the communities that surround it, creating a collective intelligence that expands the game’s extent from the day it is released(and often, with particularly engaged communities, before this). As such, our research attempts to unravel these game worlds in the same way an architect or an urban designer would analyse a real site or space. The aim is to comprehend these worlds as they are presented to us by the game – as its citizens, forming our own interpretations from what is offered, and discover what capacity we have to affect the environment within its given constraints. This allows us to position game worlds not only in their relation to the architectural discipline, but also their connections out to urbanism, anthropology, politics and history.

Our research attempts to unravel these game worlds in the same way an architect or an urban designer would analyse a real site or space.

We use analytical techniques that are broad and adaptive, from retracing in-game paths already taken and creating new ones, to “noclipping”4 by applying cheat codes and making unorthodox journeys to generate information. We have counted steps and surveyed different sites, climbed up and jumped from buildings hundreds of times, and driven back and forth over hills. We employ data-mining techniques and camera tools to reveal angles and information that would not normally be presented to the player but are key to maintaining their experience of the world. Our research is different to the picture that the game’s developers could give us – instead we see this as a record of the architectural limitations and possibilities that each game world affords. If a game is harder to get a particular type of information from, then that in itself is interesting.

Beyond our own primary research through play, we work with the vast bodies of information created around each game by its player communities. Much of this information is hiding in Discord channels, Reddit boards, game wikis, forums and YouTube clips. While insights from game developers allow us to understand certain systems first-hand, much of the prevailing knowledge of these games is unofficial and developed through research made by players. This means that there are expansive “folksonomies”5 that surround most games, and our research folds this knowledge into the more “official” accounts of the game, as well as our own, to reflect that there are many, parallel, bodies of knowledge about these worlds that coexist and may even contradict one another.

While insights from game developers allow us to understand certain systems first-hand, much of the prevailing knowledge of these games is unofficial and developed through research made by players.

Our research has covered multiple games and spatial themes. We explore Assassin’s Creed Unity (2014) as a form of historical re-enactment, accessing architectural landmarks in ways that are impossible in reality. Our studies of community mods in Cities: Skylines (2015) shows how the player base has challenged the games’ Americanised urban model. By placing the world of Dark Souls (2011) into a lineage of picturesque architecture and garden design we understand how it draws people to and through an uncaring and deadly world. We analyse the desolate geography of Death Stranding (2019), revealing new ways of reading its American landscape through the blank spaces of logistics and non-human architecture. A relationship to landscape has led us to examine a world constructed entirely from scratch: the procedural environment of Dwarf Fortress (2006), analysing how players design for this most inhospitable of worlds. We can see how the architecture of game worlds physically represents the hierarchy of its society in the layered radial city built around a towering corporate headquarters in Final Fantasy VII (1997) and its Remake (2020). And we also track environments undergoing more constant updates, such as the world of Fortnite (2017) which is dictated by an ever-evolving storyline that influences its physical development as well as its overriding narrative.

Game worlds often provide bizarre mirrors to reality such as Katamari Damacy (2004) which tells a tale of consumerism within a messy, seemingly illogical world, assembled from thousands of everyday objects. Moving from the ball to the block, our analysis has peeled apart the expansive world of Minecraft (2011) by highlighting three notable servers that showcase the spatial and social desires of players. Our studies of No Man’s Sky (2016) demonstrate the social spaces and connections that players make to give themselves some form of foothold in a near-infinite universe. Through visual analysis connecting the world of Persona 5 (2016) to real-world Tokyo we can see how the shift between the everyday and supernatural is anchored through domestic and mundane spaces drawn from reality. Finally, our research on Stardew Valley (2016), shows players fleeing the city in favour of a life on the rural homestead, only to end up working the landscape square by square both by virtual hand, and by extending the game through automated farming modifications.

Our work to outline the architectural significance of each of these games, while operating as independent pieces of analysis, also adds to our understanding of the urbanism of interactive game worlds, unravelling all the many spatial messages we receive from the moment we pick up the controller and start a new journey.

Excerpted and adapted from Videogame Atlas: Mapping Interactive Worlds (Thames & Hudson, 2022)

Bio

Sandra Youkhana is a Lecturer at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL and a registered Architect. She is co-founder of You+Pea, a design research studio working between architecture and videogames. Sandra co-leads the Videogame Urbanism studio at UCL, examining how games can help shape the future of urban design. Sandra has consulted for game developers, technology companies, and city planners, and is currently undertaking a funded PhD at UCL. Her research investigates videogames as design platforms, exploring the architecture of collaborative, virtual worlds.

Luke Caspar Pearson is an Associate Professor at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL. He is co-founder of You+Pea, a design research studio working between architecture and videogames. Luke co-leads the Videogame Urbanism studio at UCL, examining how games can help shape the future of urban design. Luke has written on the relationship between architecture and games for publications such as FRAME, eflux Architecture and Disegno and was a Guest Producer for the Serpentine Galleries Future Art Ecosystems 2: Art x Metaverse strategic briefing. Luke’s previous books are Architectural Design: Re-Imagining the Avant-Garde (Wiley, 2019) and Drawing Futures (UCL Press, 2016).

Notes

1 Jesper Juul, Half-Real (Cambridge MA & London: MIT Press, 2005).

2 Madelon Vriesendorp, Flagrant délit (1975).

3 Mark Monmonier, How to Lie with Maps (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1991), 25.

4 Noclip is broadly defined as the suspension of game physics allowing “ghosting” through walls. A definition from Doom creator John Carmack was referenced by Twitter user @me_irl following an email conversation with @ID_AA_Carmack (John Carmack) posted 11:50 PM - 16 Nov 2012. “john carmack on “no clipping””. [link]

5 Oxford Languages defines a folksonomy as “a user-generated system of classifying and organizing online content into different categories by the use of metadata such as electronic tags.”