Consolidating a confidence in reciprocal, collective and intersectional practices: Federica Zambeletti guides a conversation featuring architect Pedro Aparicio-Llorente, founder of APLO and artist Daniel Blanco; Christina Serifi and Anthony Powis from MOULD collective, and Janna Bystrykh and Alina Palais, two of the five members of the curatorial team at the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam 2024.

The conversation has been developed within the context of a media partnership with the International Rotterdam Architecture Biennale "Nature of Home."

FEDERICA ZAMBELETTI / KOOZARCH It’s a pleasure to bring you all — Christina and Anthony from MOULD, Pedro and Daniel from APLO, Alina and Janna from IABR — together in conversation today. My first question arises from the title of this Biennale, which is Nature of Hope: how does hope guide your reciprocal practices?

ANTHONY POWIS One of the things I was going to bring up in relation to hope — and fundamental to that idea of reciprocity and hope — is this conversation between the future and the past, always. I have this poster on my wall by Autonomous Design Group, an anarchist graphic collective in London. It has a Paulo Freire quote which says, ‘Without a vision for tomorrow hope is impossible.’ It speaks to that reflexivity between hope and future thinking; one is fundamental to the other. You can't really have hope without visioning, and you can't really envision without hope — why would you? In that sense, it's fundamental.

But I like the way you describe hope as being a reciprocal practice; that's also how we conceive of it within our work as MOULD and within our installation as well. It speaks to the critique of the past as being fundamental to the projection of futures; you can't really do one without the other. I think that's where, particularly for me, our practice of hope and envisioning comes through this lens of critical analytical thinking as projecting the future.

CHRISTINA SERIFI When working with climate and the entanglements of climate breakdown with architecture, it's quite easy to fall into despair, when you realise that things are quite gloomy! In our work, Architecture is Climate, we have talked with many people from different fields, organised multiple conversational encounters and workshops, and gathered a large laboratory of practices from around the world, all pointing towards other ways and potentials for spatial practice. This part of our research brought us a lot of hope, because we realised there are many networks of solidarity, various forms of organisation, governance and collaboration and many people working towards and fighting for similar causes. These alliances are important in maintaining a feeling of hope, but also to act upon it across many different contexts. It is important to see what other people are doing and feel part of this ecosystem.

"Alliances are important in maintaining a feeling of hope, but also to act upon it across many different contexts. It is important to see what other people are doing and feel part of this ecosystem."

- Christina Serifi

KOOZ It’s inspiring to see you finding hope in others and by growing these networks of solidarity — which is what IABR has tried to do this year. This also seems pivotal to the work of APLO, in its approach towards the thresholds between architecture, natural and planetary concerns.

PEDRO APARICIO LLORENTE Yeah, I align with that sentiment a lot. There's something about this idea of reciprocity and networks which comes down to companionship, to feeling accompanied. There's a certain degree of hope in that, because everyone here — and you can see it in the exhibition — recognises that they're walking a long walk. It's that feeling of going slowly, but going far; it's going to be a long, long journey. To feel accompanied in this action feels important and it nurtures the process because ultimately, what we are doing — more than project-based work — is a long-term process, it requires patience. In the Amazon, elders say that once you pass the night talking, it's only in the early morning when the sun rises that words are born. That's when words (or worlds) actually reveal themselves. So there's something about patience and hope that I think is interesting. I remember talking with Daniel about the theme of hope too —

"When we, as a tool of the practice, need to develop conversations and participatory actions, we start to reevaluate and even replace the word hope with the notion of trust."

- Daniel Blanco

DANIEL BLANCOYes, I do remember this conversation with Pedro, on the process of designing a landscape, for example. When we, as a tool of the practice, need to develop conversations and participatory actions, we start to reevaluate and even replace the word hope with the notion of trust — because hope is somehow a projection of what you believe is going to happen. You put your hope or trust into whatever action that you are developing; we thought that trust was also a meaningful term for interlinking and acting together.

In more practical terms, my process as an artist also involvestrust, perhaps in the act of meeting or confrontingthe presence of someone else, trusting that they will be able to experience gravity and balance of installation-sculpture-space, and to trust that it is going to hold together — especially as I like to build with the minimum that is necessary. Maybe this is architectural or a reference to arte povera but in building with only what is necessary, one finds the evidence of trust between people.

KOOZ I have two questions. Firstly, I love the fact that you raised the term minga. There are certain words — and certain spatial practices — which don't exist in English and Anglophone cultures. To what extent has this constant translation caused us to forget more local approaches to architecture?

The second point circles around this idea of time: when one proposes a process rather than an outcome, ultimately that project doesn't end. On one hand, we’re thinking about design at an intergenerational scale, posing questions which really transcend a human timeframe, while MOULD’s diagram, for instance, carves out a very distinct timeline — 1850 to 2023.

PAL I’ll share some thoughts on language. The words that relate to the way that we do architecture are perhaps not part of the common architectural jargon, but they are linked to the processes that we work with. For example, Veanvé — the project where we were invited to consider the transformation of a decommissioned telecommunications station, into an artistic and cultural centre on the Pacific coast of Colombia. It's called Veanvé after a slang word from the Chocot region, which means ‘look and listen’. This regional slang combines and complicates the understanding of language and space with a type of action, introducing factors of time; it becomes quite relevant and will eventually help to shapethe building.

"The words that relate to the way that we do architecture are perhaps not part of the common architectural jargon, but they are linked to the processes that we work with."

- Pedro Aparicio-Llorente

Another example is the term “payao” that was brought in not from any local ancestral condition; rather it was imported from the Philippines to the Colombian coast. This speaks to ideas of multiple realities, globalisation and other divergent types of connections that the contemporary world is racing through. These words — like payao, which is completely abstracted and transpacific, or veanvé, which is totally situated in space and time, relate to a particular way of feeling and looking — they shape the way that we connect to these ideas and become part of the process… Which is, again, a process of mutual trust, involving a lot of people. We come in with questions of visualisations and providing technical representations, which then become part of the conversation. What's interesting is that the conversation is moving in many different directions at once. Our conversation right now will probably circulate within the architectural discourse; similar currents can be found in discussions of migration and biodiversity. I think there's something interesting about decentralising architectural building as the centre of the process. It's just one more asteroid that is looping around a certain energy or certain forms of energy.

ALINA PAIAS Perhaps there are other definitions for when you feel inspired — for instance, by a lecture or an exhibition — but at the centre of hope, there is a collective project and some notion of building through the other. It’s not simply a matter of feeling inspired or assured by that other; rather, by being in contact with so many others, you avoid this trap of reinventing the wheel by yourself. More than just words, I would say that language is a technology as well; a word can be technology in the sense of giving access to knowledge across trans-cultural communication. It goes beyond finding someone who agrees with you, but extends to exchanging techniques, technologies and strategies. That's the truly hopeful collective construction, and that’s amazing.

"At the centre of hope, there is a collective project and some notion of building through the other."

- Alina Paias

DB I am also interested in how technology becomes language, because I think by being present in this context, for example, on the Pacific Coast — and aligned with this idea of decentralising language itself — I do believe that people tend to develop more analogical ways of communicating.

Then too, I do believe that language is also image and matter. I like the way that Josefina [Klinger Zúñiga] speaks, for example, of the decorated shore as a way to talk of stationary marine cycles. Looking closely at what materials, technologies and images reside in a certain place allows an easier communication with that place.

AP-MOULD I’ll speak about time, before handing over to Christina on language. The question of the timeline and our installation is, in a way, all about languages. On one side of our installation, we have graphed the level of greenhouse gas emissions. Now, it's completely wrong to imply that conversation about climate change begins in 1850. It should start long before that, in the early colonial periods — when all the terminology, language and ways of thinking, which appear on the other side of the diagram were first created, practised and embedded. The problem is that you don’t really see it on the graph until 300 years or so later, because of the scale of what’s being emitted now. So the graphic of it actually muddles our story. It's the same issue that geologists face in trying to find the ‘golden spike’, which measures the beginning of the Anthropocene as a geological period. They actually locate it as some time in the middle of the 20th century; that tells a particular story about what the Anthropocene is, because it has to be measured in a certain way. We end up accidentally doing that with our graphic representation, but the words in it speak to a much deeper history.

"We talk about ‘violating’, ‘ignoring’ or ‘band-aiding’, exposing the ways in which architecture applies what we call ‘patches’ for planetary wounds, without dealing with their actual causes."

- Christina Serifi

CS We’ve actually talked a lot about language within MOULD, firstly as six people from different backgrounds and contexts. It gave us a sense of possibility and opportunity in terms of how to work collectively across academic contexts. We’ve also faced this challenge in collective writing, searching for languages and formats that would represent us all and exploring ways to talk about architecture and climate in a simple and understandable manner, while maintaining a sense of hope. We have deliberately challenged how written work is often produced in academia, by avoiding hierarchies and producing articles, papers and visual formats where we are equal co-authors. Through this ongoing process of co-writing, reading, editing, and sharing, we have learned a lot.

Our installation, Architecture is Climate at IABR used two languages, broadly. As a visitor, first you encounter a dark embroidered diagram of the foundations of architectural production, depicted in black and white. This cuts through a symbolic mountain, the slope of which represents centuries of CO2 emissions. Along the left side is a powerful list of verbs, describing the violent forces of architecture that have accelerated CO2 emissions in different contexts. We talk about ‘violating’, ‘ignoring’ or ‘band-aiding’, exposing the ways in which architecture applies what we call ‘patches’ for planetary wounds, without dealing with their actual causes.

One of the challenges, as Anthony said before, is to look and understand the past, the causes and how we got here, in order to act and find hope in the future. We cannot build equitable futures if we don't remember and understand the inequalities and operations of the past; that’s what the diagram brings forward. On the back, we use a lighter visual language, representing futures. We speak through the multiple projections of prompts, as we call them, to inspire further and multiple actions. These ways of acting are drawn from various current practices on our website, compiled into a playful resource that offers possibilities of how viable futures could be enacted.

KOOZ It is pertinent to note the use of drawings and graphs as language too; moreover, visual languages can often help us expand beyond architecture to a more collective, interdisciplinary kind of pool of thinkers. At IABR, much space is given to the power of visual communication. How important was it to you that the content portrayed was made accessible for the citizen?

AP-IABR Honestly, this is a constant tension, and not an easy problem to convey. You want to do justice to what these works look like for the discipline, so I do think you need to use the language that belongs to spatial practitioners to do that. But there’s a clear intention to have these works not only speak to their own audiences, but also to members of the general public. We wanted to generate a perception for all visitors of how broad architectural practice can be, and the huge range of issues that architecture is equipped to face. The intention was to provide the general audience with an impression of how architecture is materially and historically enmeshed and entangled with how we're living today — and to ask how it might respond to that.

"We wanted to generate a perception for all visitors of how broad architectural practice can be, and the huge range of issues that architecture is equipped to face."

- Alina Paias

JANNA BYSTRYKH It was our ambition to establish that the ongoing discussions and transformation of practice are not limited to the professional field, but directly engaged with many societal questions. Choosing to focus on nature was part of that. Climate is a global emergency but as a term, it can create a certain technical distance from daily realities and focus of people individually. By foregrounding nature, focusing on restoration of biodiversity and other biodiversity goals, we inherently address many of the needed climate actions. And by focusing on nature, we hope for the urgency, possible actions, and paths towards an ecological practice to become more accessible and relatable, for people within architectural practice and beyond.

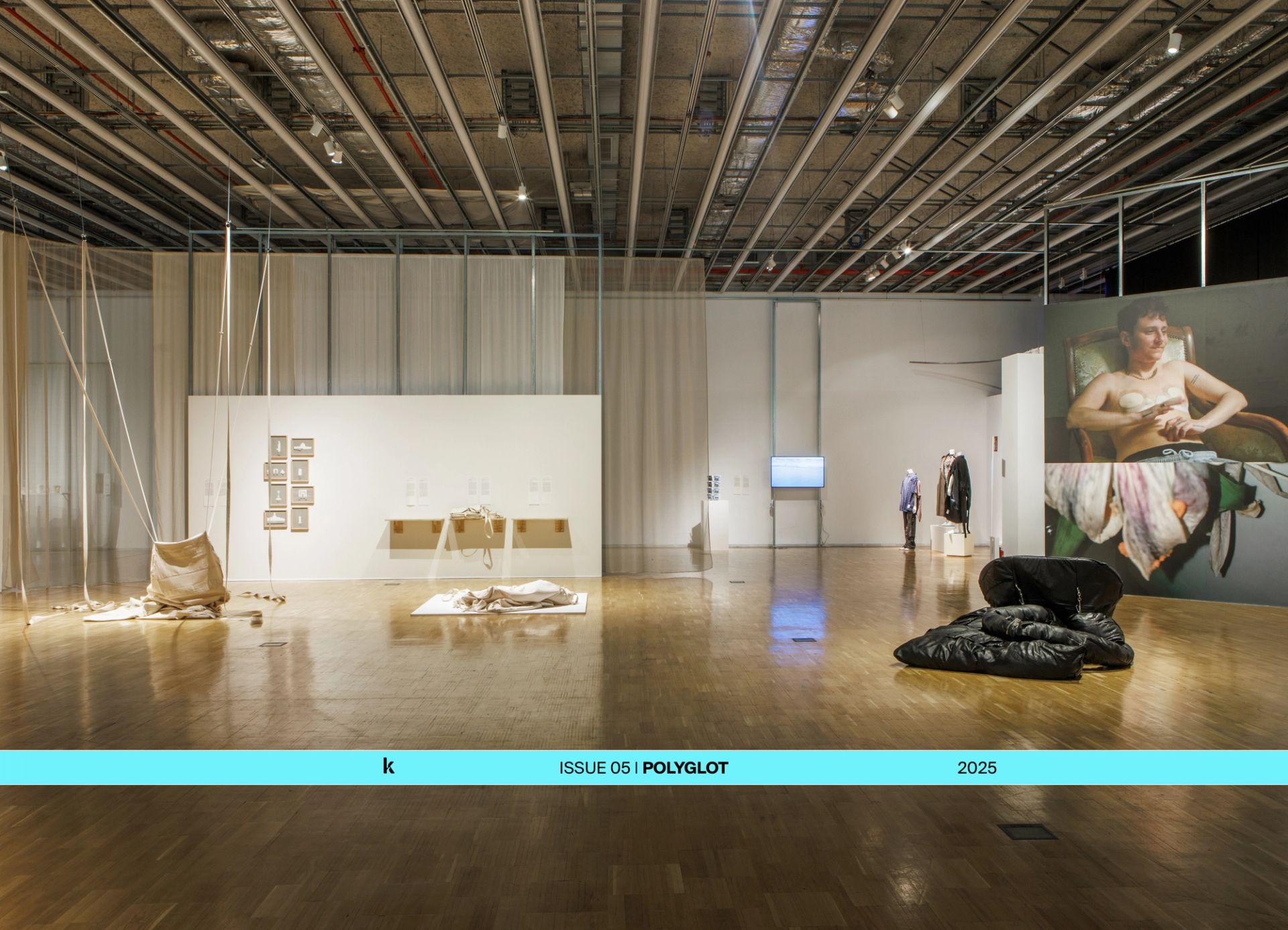

In the exhibition, the visitors are initially taken on a journey exploring various relationships with nature and their shifts over time, highlighting several moments in the understanding and interpretation of that relationship, as well as moments of coexistence and even the breakdown of that relationship. The introductory space contextualises the necessary professional shifts within a wider discussion on regeneration. Another goal was to strike a balance between experimental work, practice-oriented work and research, and between the installations.

Some works are perhaps more oriented towards capturing the imaginary, while others relay the day-to-day practices of change, where we can already see a different mode of architecture emerging. Lastly, we also tried to look along the chain of stakeholders involved in the production of architecture: that is to say, not only celebrating the final building but also the shifts in policy making or new legislation, or the celebration of soil. In so doing, we hope to find resonance with different visitors, with their worlds and their experiences.

"By focusing on nature, we hope for the urgency, possible actions, and paths towards an ecological practice to become more accessible and relatable, for people within architectural practice and beyond."

- Janna Bystrykh

KOOZ Thank you for sharing. Pedro and Daniel, how do you position your practice in terms of working upstream or downstream flows of power and change?

PAL As you might know, we've been thinking about media for some time now. Specifically, how to put the visual capacity of architecture in alignment with processes that affect the everyday life of people in regions with high biodiversity. We quickly found that we had to start creating content for youtube for example; also considering how such media moves, we had to keep it very light — so it can easily be shared through WhatsApp messages, group chains and so on.

This actually relates to the previous question about the medium of the exhibition. Very early on in our interactions with the IABR curatorial team, we felt that the conversation was quite honest. We were able to state that we’re not interested in retrospective work or in encapsulating a certain moment; rather, the work for the exhibition should generate or propel the advancement of process for the future, and the curatorial team was very supportive. We proposed live drawings and research on the ground; building, documenting this work; finally, to present and exhibit at the Biennale.

In parallel the films we created for the show1 are spilling out in other places. Josefina Klinger is sharing it with potential allies at the Festival of Migration, and in advance of the COP16 Conference on Biodiversity, which takes place in Cali, Colombia in a few weeks. The video encapsulates and conveys a certain tone for that. The Payao video was presented recently at a convention for fisheries. So, media moves in multiple directions; links are spread far and wide through WhatsApp, Telegram and so on.

It's interesting that you talk in terms of flows. What we're seeing is that the river doesn't start up high and end at a low point: the river is constantly recharging itself. The river can also be born in the delta, from rain. This is a very cyclical way of working; in our case the contemporary question of an exhibition was framed from the curatorial side, which then allowed us to realise a project which supports a specific moment in a long-term process, and then there are these spin-offs that move in different directions. Architectural representation can be very generative for visualising futures, but their potential will only be realised when we really harness media. In the end, it is through various media that we share the flows of our process.

"Architectural representation can be very generative for visualising futures, but their potential will only be realised when we really harness media."

- Pedro Aparicio-Llorente

KOOZ I think that's pivotal: maybe it's not about a particular medium, but how forms of media can nurture a collective dialogue. In architecture, it often seems imperative to plan or orchestrate — but the beauty in the connections that we’ve been describing often come from un-planning. How open are you towards embracing the generative, the spontaneous and incidental? How easy is it to change the stream of your river, so to speak?

DB I remember attending a certain programme — run by APLO and Julianna Ramirez — at the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, called Forest Classroom. The sound artist Leonel Vasquez raised a question: he asked if it was necessary to do something — perhaps it was not necessary to do anything at all. I believe that confronting this possibility of not designing anything brought power to the project. The proposal was about how to create an artificial reef on the Pacific coast; then, anticipating the ecological succession that could happen was maybe more powerful than doing anything at all. I like to think that maybe we can reposition our role as architects or creators; maybe not needing to do anything, is a way to think about this idea of flows. Maybe you just need to look closely and listen; maybe what's necessary is the least action.

"Maybe you just need to look closely and listen; maybe what's necessary is the least action."

- Daniel Blanco

CS I would echo that. I think it's really important to talk about architecture, beyond the buildings and beyond physical constructions; architecture is also social relationships, about processes and alliances. We talk a lot about that in MOULD, how to reimagine and inform new social relations. This is one of the reasons that we insist on using the term ‘architecture’ in our work, which is somehow appropriated by dominant construction practice. In many contexts, when we talk about architecture, we tend to mean buildings. What is amazing is that this Biennale is talking about policies, about other economies, about ways of collaborating together — and this is what we also try to do through our work, ‘Architecture is climate’ — bringing all these processes in order to inform other ways of being, doing and working.

KOOZ The exhibition has very generously drawn upon twenty local initiatives, as working examples of a resilient system. What prompted the IABR team to expand its programme beyond the institutional walls, leading visitors through a range of local and civic spaces?

JB The ‘Botanical Monuments’ were initiated to emphasise daily rituals with nature in an urban setting; the importance of coexistence in the urban environment. We set out to find existing initiatives, which are staging different forms of coexistence with urban nature — by doing that trying to help broaden our focus in appreciation of urban nature, beyond aesthetics and as simply effective food production sites for example. Botanical Monuments became a collection of a range of initiatives and ways in which people are relating to nature in the city by being, caring and exploring. Finding and connecting to these locations was a fantastic journey in itself. The aim of the program and format is also to share the incredible drive people have in caring, and sharing their narrative in this network of urban nature projects.

Another important aspect of the program relates to biodiversity in the Netherlands specifically, the levels are some of the lowest in Europe, but the highest marginal improvements are in cities, as well as in river and dune landscapes. So there is an important conversation in this context and action in relation to nature in cities and biodiversity restoration in general. This also includes soil; much of the open soil in Dutch cities is interrupted by infrastructures in the soil, which impact and limit soil ecosystems.

The initiatives are additionally connected through an online platform, where visitors can find stories and programs organised across different sites. We hope this network will continue to grow, and that people can continue to discover and share narratives in their neighbourhoods across the city and its surroundings, through the BM platform.

AP-IABR I’m thinking about upstreams and downstreams with regards to the Botanical Monuments. The institutional context of IABR has a long and strong history of design research. This year, we developed this position that we would talk about urban nature — about biodiversity and ecological systems in the city — not by looking at the city as a speculative design object, but from a very situated perspective. We wanted to see how conversations on strengthening and caring for urban and planetary health could start from each location, each with its own situated ecologies, before starting to associate them. In terms of moving upstream, that was very much an underlying current.

AP-MOULD I also want to say thank you to Pedro for his comment on the upstream and the downstream, that the river is not a line where the upstream is just one thing and the downstream is just one thing. I'm going to keep thinking about that. There's another beautiful metaphor that I read from a hydrology textbook which states that conventionally, we think of the river as being the veins of a leaf — but really it's the entire leaf. It's the whole landscape.

KOOZ That's such a beautiful metaphor, and a great way to end the conversation. Thank you all so much.

Bios

Pedro Aparicio-Llorente is a Colombian architect and educator who designs and researches buildings and landscapes through multispecies technologies. Aparicio leads APLO (Alineando Planetas) Oficina de Arquitectura, a Bogotá-based practice that emerges from ten years’ experience in design and construction in political and material ecologies of postcolonial tropical habitats. Thinking and doing through multispecies technologies, his questions engage volcanic, riverine, and oceanic space.

Daniel Blanco Lozano has a dual degree in architecture and fine arts, his practices flow loosely between both disciplines and pedagogy. His work explores situated material cultures and questions how the tools of making become bridges between people and ecosystems: sometimes by words, other times by encountering, and specially through the act of building itself. Currently he works as an independent designer making exhibitions, furniture, renovations and offering workshops or educational programs in both: popular or academic environments.

Janna Bystrykh is an architect and researcher. She is the head of the Master in Architecture program, at the Academy of Architecture Amsterdam, where she leads the development of a climate curriculum for architecture, and runs her design and research practice BYSTRYKH. Bystrykh has experience with complex urban projects, museum transformations, experimental education and installations. At OMA, she worked on the ‘Elements of Architecture’ exhibition for the 2014 Venice Biennale and on the research and exhibition project Countryside: The Future.

Alina Paias has a background in architecture. She works as a designer, researcher and curator. She immerses herself in feminist philosophy, new materialism, environmental humanities and the philosophy of technology, from which she explores the creation of architecture. Paias works as a spatial designer at CLOUD and as a guest lecturer at Delft University of Technology. She has also worked as assistant curator at RADDA in São Paulo.

MOULD is a research collective of Sarah Bovelett, Anthony Powis, Tatjana Schneider, Christina Serifi, Jeremy Till, and Becca Voelcker. MOULD’s latest research project, Architecture is Climate, grew out of the research grant Architecture after Architecture: Spatial Practice in the Face of the Climate Emergency, funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). The project is supported by Technische Universität Braunschweig and Central Saint Martins (UAL). More information can be found at architectureisclimate.net.

Federica Zambeletti is the founder and managing director of KoozArch. She is an architect, researcher and digital curator whose interests lie at the intersection between art, architecture and regenerative practices. In 2015 Federica founded KoozArch with the ambition of creating a space where to research, explore and discuss architecture beyond the limits of its built form. Parallel to her work at KoozArch, Federica is Architect at the architecture studio UNA and researcher at the non-profit agency for change UNLESS where she is project manager of the research "Antarctic Resolution". Federica is an Architectural Association School of Architecture in London alumni.

Notes

1 Veanve: Veanvé (English Subtitles) / Payao: Payao (English Subtitles)