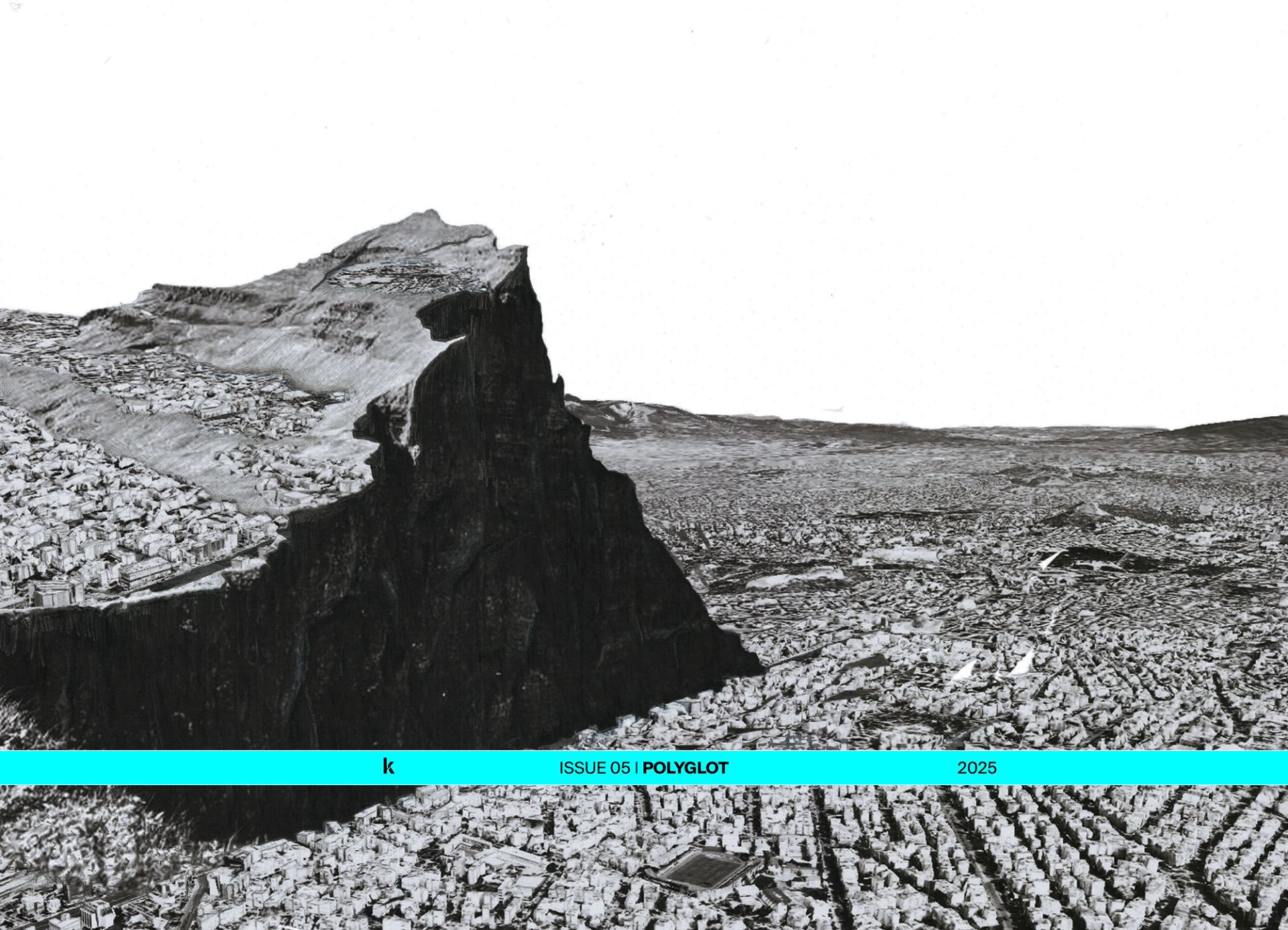

The project addresses the National Monument of Scotland, a structure that began as a popular 1822 proposal to build no less than an exact replica of the Ancient Greek Parthenon atop Calton Hill in Edinburgh to commemorate fallen soldiers of the Napoleonic Wars. Yet, when construction ended in 1828, only a fragment of the initial proposal crowned the hill. The partial Parthenon is seen as a failure so severe that the monument is still referred to as “Edinburgh’s Disgrace” and “the Pride and Poverty of Scotland” to this day. The structure’s fragmentary status as a “readymade ruin” causes it to be a projective device for shifting Scottish national identities in ways a more “complete” monument never could. The installation revived various historical initiatives to complete the seemingly unfinished monument - as catacombs for national heroes, as an extension of the National Gallery, and as a full Parthenon replica - rendering them according to “pnue” aesthetic principles as digital soft body geometries inflated under simulated pressure. A literal “blowing up” of history. The three follies initiate a process of unlearning the entrenched values of the western tradition through an irreverent digital pageant that collides the Neoclassical with the contemporary in a spectacle of mutual absurdity.

Project developed for Architecture Fringe, 2021.

KOOZ What prompted the project?

IE | RM | OM | SP The project began with an interest in how identity is negotiated and constructed through architecture, often across physical and historical distance. Monuments are potent sites of such identity formation, and we found the National Monument of Scotland to be a particularly fraught exemplar of this process. It was built in the 1820s during a wave of Neoclassical fervor in Europe when there was seemingly no better architecturalization of Scottish national identity than a faux ancient Greek temple. In the two centuries since its construction, it has served as a foil for ever-shifting national identities and public opinions that are at times sympathetic to and at times in opposition to the structure. In working on a virtual installation at the National Monument of Scotland in Edinburgh as a group of architecture students from the United States in the early 21st century, our remote work echoed the mediation of the design and construction of the original monument. The Scottish architects of the structure, Charles Robert Cockereland and William Henry Playfair, were similarly separated by time and space from the Ancient Greek Parthenon they sought to copy, designed by Ictinus and Callicrates 2,200 years prior at a site 2,300 miles away.

The project began with an interest in how identity is negotiated and constructed through architecture, often across physical and historical distance.

KOOZ What questions does the project raise, and which does it address?

IE | RM | OM | SP The primary question the project addresses is, “how does a monument in ruins affect us differently than that of its whole counterpart?” In the case of the National Monument of Scotland, the monument’s status as an incomplete “readymade ruin” has imbued it with aesthetic powers beyond that of a complete structure. Sir Nikolaus Pevsner observed the faculty of the fragment as far back as 1971, writing in The History of Building Types that the monument had “acquired a power to move which in its complete state it could not have had.” Our project draws attention to this phenomenon by “completing” the structure in ways that illustrate its incompleteness. In a way, rather than addressing the monument itself, the project addresses the conceptual and literal void adjacent to it that has served as a space for different attitudes and reimaginings of the structure over time. While our work’s attitude toward the site’s history is evident, the project is still grappling with questions the project raises about the status of virtual memorial architecture and the relationship between monuments and social media at large. To explore these broader questions further, we are investigating the digital afterlife of the Pnue History project for the forthcoming 30th issue of Princeton University’s architecture journal Pidgin.

KOOZ How does the project explore and challenge the potential of digital tools and the digitalization of architecture?

IE | RM | OM | SP The project is digital architecture made with digital tools. Yet, in many ways, the three follys follow in the conceptual footsteps of the rich tradition of radical physical architectural inflatables (Ant Farm, Haus Rucker Co) with the digital installation similarly producing space cheaply and without permission, using minimum surfaces to maximum effect in an aesthetic institutional critique. The digital platform of the AR installation allowed us to effectively sidestep strict governmental regulation of the area, the monument’s status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, pandemic-era travel restrictions, and other material and fiscal constraints. It is precisely these ways in which digital tools democratize the ability to operate upon hybrid digital-physical space that we were excited to leverage in this project.

We hope our project points towards a future where these platforms allow rich engagement between the public, architecture, and history through ubiquitous tools with massive audiences.

KOOZ How and to what extent do these digital experiences have the power of redefining our relationship to architecture?

IE | RM | OM | SP Augmented and mixed reality content is redefining our relationship to architecture and the “digital.” Currently, the most widely-used version of the public-facing digital architecture is found in AR social media filters, which span across operating systems and devices. As platforms hosting such content become more widely used, architecture will have to increasingly confront its extension/remixing/subversion in digital mixed reality space. Keiichi Matsuda explores some ways this might happen in his quasi-dystopian film Hyper-Reality. While all of this is yet to play out, we are excited about the possibilities. We hope our project points towards a future where these platforms allow rich engagement between the public, architecture, and history through ubiquitous tools with massive audiences.

KOOZ What is the power of the architectural imaginary for you?

IE | RM | OM | SP We admire how Neyran Turan’s work explores the architectural imaginary’s capacity to prompt new aesthetic and political lines of inquiry for the discipline. While her work primarily addresses environmental concerns, we direct the architectural imaginary towards issues of classicism, history, nationalism, and identity. For us, the power of the architectural imaginary is found in its capacity to probe these kinds of urgent subjects, which might seem exterior to architecture but are actually central to its makeup.