Part road-movie, part fictional distillation of a life in architecture: Rear View is a six-part experimental column by Jing Liu, architect and co-founder of the Brooklyn-based design firm SO-IL. The subjects and spaces described in these little journeys move between the poetic and banal; along the way, we are asked to consider what we find en route as well as everything we bring with us. In the second instalment of Rear View, we join her along her gently auto-ethnographic and semi-fictional journeys. In Bruges — once the epicenter of the medieval lacemaking and wool trade — the traveller notes stillness and continuity within the confines of a Belgian beguine.

Bruges has many cobbled streets, polished by centuries of caressing feet. It has quaint canals, predating those of Amsterdam and Venice, and a brick bell tower that survived — not once, but twice — German occupation.

Bruges has a beguinage1 with a pretty name – Princely Beguinage Ten Wijngaerde.

Like many other beguinages in the Low Countries, Princely Beguinage Ten Wijngaerde has a court in the middle. In early spring, it is filled with blooming daffodils, and it is the dawn that is most beautiful. As the light creeps over the tall Carolina poplars, their outlines are dyed a faint red and wisps of purplish cloud trail over them.

The court’s perimeter is lined with a continuous low wall that is just my height — the practice of discretion, not separation. This datum is interrupted rhythmically to contain a doorway to a chapel, a storehouse, or a gate to the smaller courts behind. The smaller courts are usually enclosed by row houses of two to three stories. The walls and the houses are all white-painted brick, crowned with deeply pitched roofs of clay tiles. In summer nights — not only when the moon shines, but on dark nights too — the whiteness shimmers, as the fireflies flit to and from. And how beautiful it is when it rains!

The only structure in the beguinage that is not painted white is the tall church, which protrudes from the wall. Its unfinished brick walls are weathered, and its weathered tile roof mossed. The church looks over the houses like a mother over her children. In autumn, the evenings, when the glittering sun sinks below the edge of the roof, the crows fly back to their nests in threes and fours and twos. More charming still are the white swans on the yellowing grass, like tales from distant times. When the sun has set, one’s heart is moved by the sound of the wind and the hum of the insects.

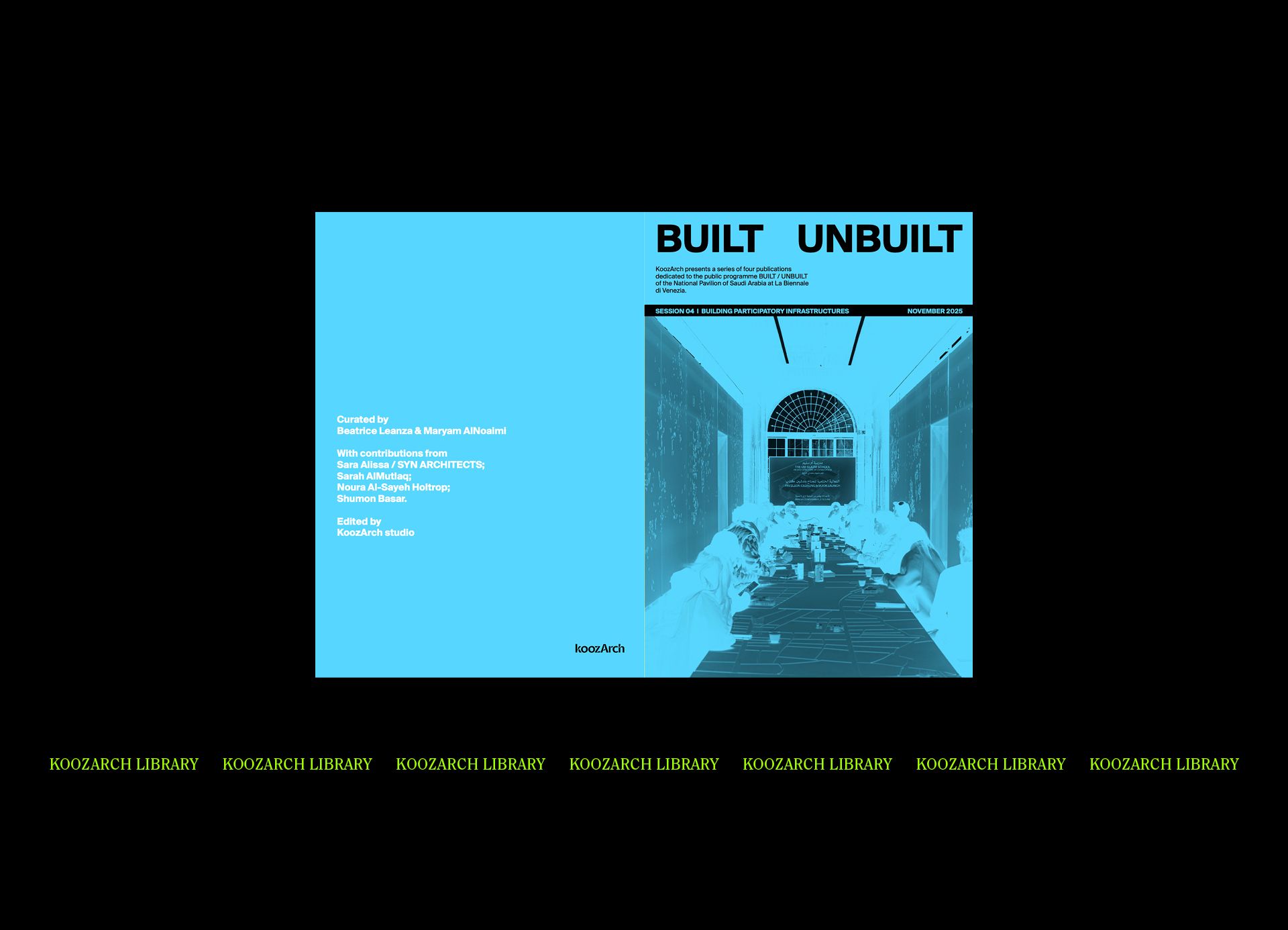

With Spaces of Possibility, the Bruges Triennial 2024’s ambition is to (re)discover un(der)used spaces in the city. SO–IL's contribution, titled “Common Thread”, is inspired by the laywomen of the medieval city, who practiced a communal and pious life outside church orders and the institution of marriage, and were responsible for the flourishing of lace-making. In collaboration with Dr. Mariana Popescu from TU Delft, “Common Thread” was knitted by a programmable 3D knitting machine from recycled ocean plastic yarns, creating a manifold, non-contiguous, tunnel-like path meandering through the cloister of the Friars Minor Capuchins, which is made open to public for the first time this year. Photo credit: Iwan Baan

In winter, the early mornings are beautiful indeed when the snow has fallen during the night, but splendid too when the ground is white with frost, or even when there is no snow or frost, but it is simply very cold: the beguines2 stir up fires, and smoke rises from the chimneys. How well this fits the season’s mood! But as noon approaches, the cold wears off, the women busying themselves with spinning and twisting and sewing, and soon nothing remains but piles of white ashes.

In the Princely Beguinage Ten Wijngaerde, the traveler encounters her kindred. Clack, clack, clack. Within its brick walls, bobbins crossed each other on the pillows laid on women’s knees.3 From behind the reedgrass screens of the Heian Palace, court lady Shonagon offered her scribbled pillow4, of undaunted praisings of the tiny beauties of the everyday. The traveler lit a lamp and ventured into these dim rooms where lives passed without words to describe them, remembrance endured without chronicles, and love permeated without tales. Lowering her eyelids, she saw that on each pillow passed down, a glistening new world.

Swoosh, swoosh, swoosh. Her Vega 3.1305 glides back and forth swiftly, knitting surfaces with threads spun from plastics drifted in oceans — the recalled waifs of our Anthropocene. xfer fNL bNL xfer bNL fNR tuck - fNL Y knit + fNR Y6… her new hiragana. Tiny threads become expansive surfaces, and expansive surfaces become manifold spaces that wrap infinite worlds within.

Come on inside. In spring, when the daffodils bloom again, in the cloister of the Friars Minor Capuchins, where the refugees from Ukraine live now. “What you are now we used to be; what we are now you will be.”7 No need to pretend to know what’s wrong and what’s right. No need to mend the dress for the zombie’s bride. Spin your wheels and tell your tales. Come inside now, and turn down the light.

Bio

Jing Liu is an architect in practice; as co-founder of the New York-based architecture firm SO-IL, she has working on a wide range of projects both in the US and abroad for more than 15 years. Liu has led SO–IL in the engagement with the socio-political issues of contemporary cities. She brings an intellectually open, globally aware, and locally sensitive perspective to architecture; projects range from artistic collaborations with contemporary choreographers to masterplan and major public realm design. Liu believes strongly that design should and can be accessible to all, and that architecture offers us an open platform to nurture new forms of interaction. To that end, Liu sees community engagement and collaboration across disciplines as central to her role as the design lead.

Notes

1 Beguinage is a residential complex where lay religious women lived in community without taking vows or retiring from the world.

2 Beguins are lay religious women who lived in Beguinages.

3 During the 13th century, textile trade flourished in the capital of the Flanders Federation – Bruges. Many lay women supported their livelihood with lace-making, which led to the development of over 1,500 kinds of exquisite patterns in the city, gaining it the nickname “The Home of Lace”.

4 The Pillow Book is a book of observations and musings written by Sei Shōnagon during her time as court lady to Empress Consort Teishi during the Heian-period (990s and early 1000s) in Japan. Sei Shōnago wrote the book in hiragana, a “plain” syllabary not used in official writings at the time, as a way for her to express her inner thoughts and feelings that she was not allowed to state publicly due to her lower standing position in the court. The book's famous opening passages, describing the beauty of the four seasons, are woven into the description of the Beguinage in the earlier part of this essay.

5 Vega 3.130 is a programmable 3D knitting machine by Steiger.

6 A string of codes written for the 3D knitting machine.

7 In the Santa Maria della Concezione crypt in Rome, some 4,000 Capuchin friars who died between 1528 and 1870 are still lying, hanging, and generally adorning the walls, reminding the monks that death could come at any time. A plaque in the crypt reads, “What you are now, we once were; what we are now, you shall be.”