A pause before the music starts, while we introduce our second columnist for this year; bend your ear towards the sounds of Ivan L. Munuera, whose selection of songs and their attendant spaces form a critical soundtrack, resonant with resistance from the Queer community. From Factory records to the favelas, Sonic Kinships sways between the struggles for freedom, justice, pleasure and a place to dance. The series starts with a meditation in high drama, on the Pet Shop Boys and Derek Jarman’s garden.

Track 01: Pet Shop Boys, It’s a Sin (1987)

The first chords of It’s a Sin fall heavy, a church organ in pop drag. Derek Jarman filmed the video for the chart-topping track in 1987, already living with the knowledge of his HIV diagnosis and later, the development of AIDS. He filled the frame with ruins, candles, fragments of architecture. Not allegory, just what was left around him — broken stone, wood, flame. As Chris McCormack points out, “Jarman’s visions arrive as ballast against the punitive responses by the state and the media towards queer lives.” Thatcher’s England was legislating queerness into silence: Section 28, passed the following year, made it illegal for schools and councils to “promote homosexuality.” Teachers could not acknowledge their students’ lives; libraries were stripped of books. The song, with Jarman’s imagery, was about the material reality of living under a law that rendered existence as unspeakable:

Everything I've ever done

Everything I ever do

Every place I've ever been

Everywhere I'm going to

It's a sin.

At Dungeness, Jarman began another work, different in scale but bound to the same time. A cottage facing the sea, its garden built out of what washed ashore. He planted roses, and though he wrote in Modern Nature, “I would love to see my garden through several summers,” he probably knew that he would not. Stones gathered into circles, driftwood staked like sentinels, rusty iron rising from the ground: a fragile architecture, but no less deliberate than the set of It’s a Sin. One made for broadcast, the other for wind and salt. Both emerged in a moment when the politics of Thatcherism pushed queer life and those living with HIV/AIDS into precarious visibility.

"One made for broadcast, the other for wind and salt. Both emerged in a moment when the politics of Thatcherism pushed queer life and those living with HIV/AIDS into precarious visibility."

The garden refused monumentality. There were no walls to block the nuclear station looming nearby, no fences against the sea. Jarman embraced toxicity, letting it flow both inward and outward. He worked with what he found: sea kale pushing through gravel, weeds rearranged as ornament, the wreckage of fishermen’s tools set upright as sculpture. He used the same methodology that shaped the mise-en-scène of It’s a Sin: gather fragments, repurpose ruins, make form from what others discard. As C. Riley Snorton has written, dissident bodies confronting the econoracial heteropatriarchy — whether marked by queerness, illness, blackness, and so on — are forced into transformation, reshaped under constraint. The same principle held in Dungeness: detritus became structure, barren soil coaxed into bloom. This garden, and these bodies, were neither about curing, nor caring. The garden embodied a practice of non-curing care, one that sustains without demanding repair. Such a practice resists the logic of normalisation, often imposed through medicalised ideas of “cure,” as people like Eli Clare and Ignacio G. Galán have argued on crip politics.

"There were no walls to block the nuclear station looming nearby, no fences against the sea. Jarman embraced toxicity, letting it flow both inward and outward."

Years later, as Jarman’s sight began to fail, he made Blue (1993): nothing but a field of Yves Klein blue while voices recount illness and loss. Like the garden, like the roses he might never see open, Blue was made in the knowledge of departure. The material pared down to almost nothing yet insisting on presence, Blue transformed vision into a palimpsest to register survival. While the video for It’s a Sin condensed accusation into its very ridiculous spectacle; the garden turned driftwood into an ecosystem of non-curative care. These were not separate gestures but variations of the same practice: making life hold, however provisionally, in the midst of disappearance. It is here that Maria Puig de la Bellacasa reminds us that care is always double: it nourishes but it also drains, tying us to futures we may never see. Gardening at Prospect Cottage was [an act of] care as endurance, a projection, gifted to others. “I grow old among the roses,” Jarman wrote. Each planting was for someone else’s tomorrow.

"These were not separate gestures but variations of the same practice: making life hold, however provisionally, in the midst of disappearance."

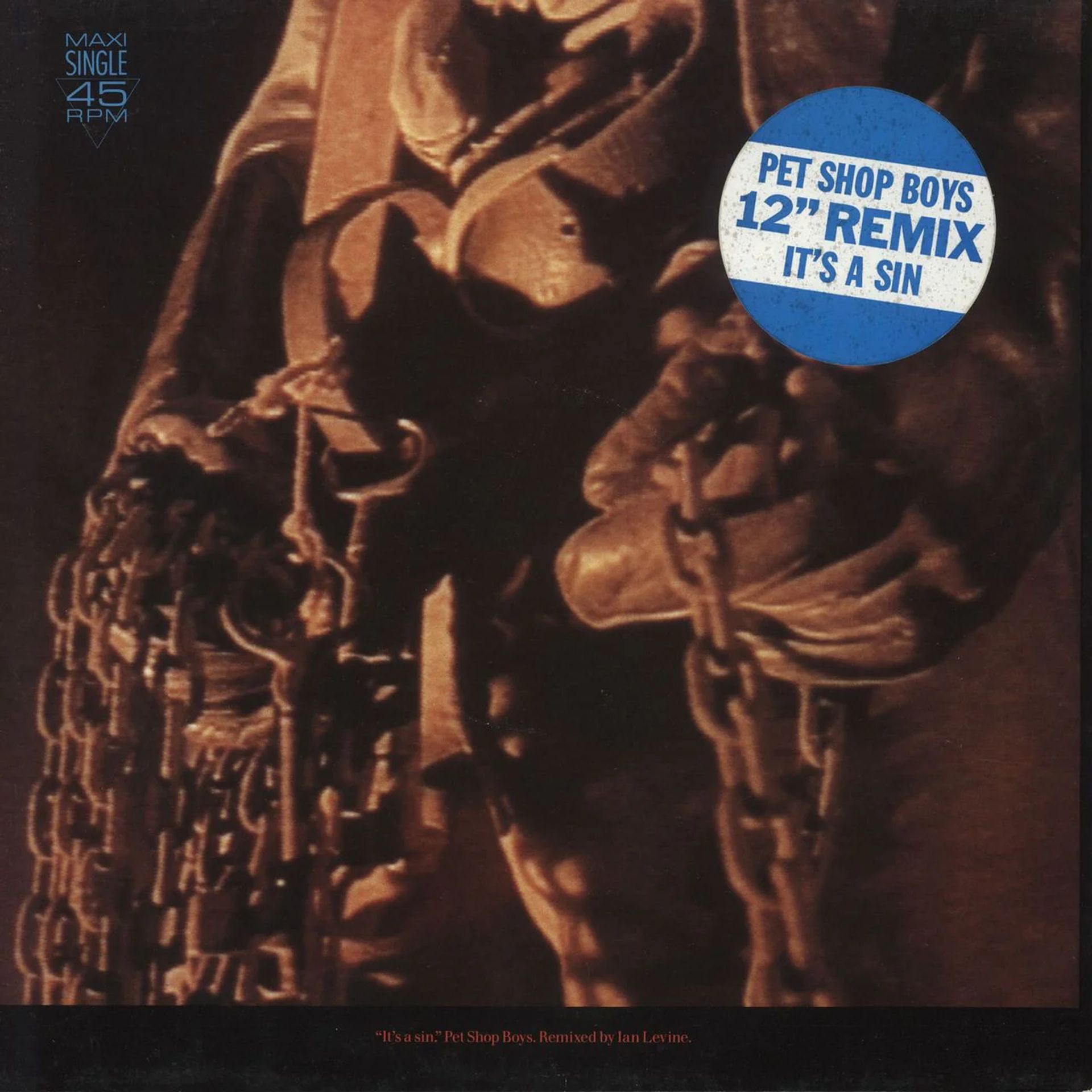

Pet Shop Boys – It's A Sin (Remix), 1987, Parlophone/EMI. Sleeve art by Mark Farrow, Pet Shop Boys.

Bio

Ivan L. Munuera is a New York-based scholar, critic, and curator working at the intersection of culture, technology, politics, and bodily practices in the modern period and on the global stage. He is an Assistant Professor at Bard College; his research has been generously sponsored by the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies and the Canadian Centre for Architecture. In 2020, Munuera was awarded the Harold W. Dodds Fellowship at Princeton University. Munuera has presented his work at various conferences and academic forums, from the Society of Architectural Historians and the European Architectural History Network to Columbia GSAPP, Princeton University, Het Nieuwe Instituut, CIVA Brussels and ETSAM, among many others. He has also published widely, from the Journal for Architectural Education (JAE), The Architect’s Newspaper to Log and e-flux.