And the beat goes on: the second track from guest columnist, critic and curator Ivan L. Munuera, is El Muerto Vivo (The Living Dead), a deeply ironic deep-cut recorded by Spanish-Romani rumba singer Peret. Munuera’s selection for Sonic Kinships — of music and its attendant spaces — form a critical compilation, resonant with resistance from minoritised and Queer communities.

You can listen to this and the rest of the Sonic Kinships soundtrack [here].

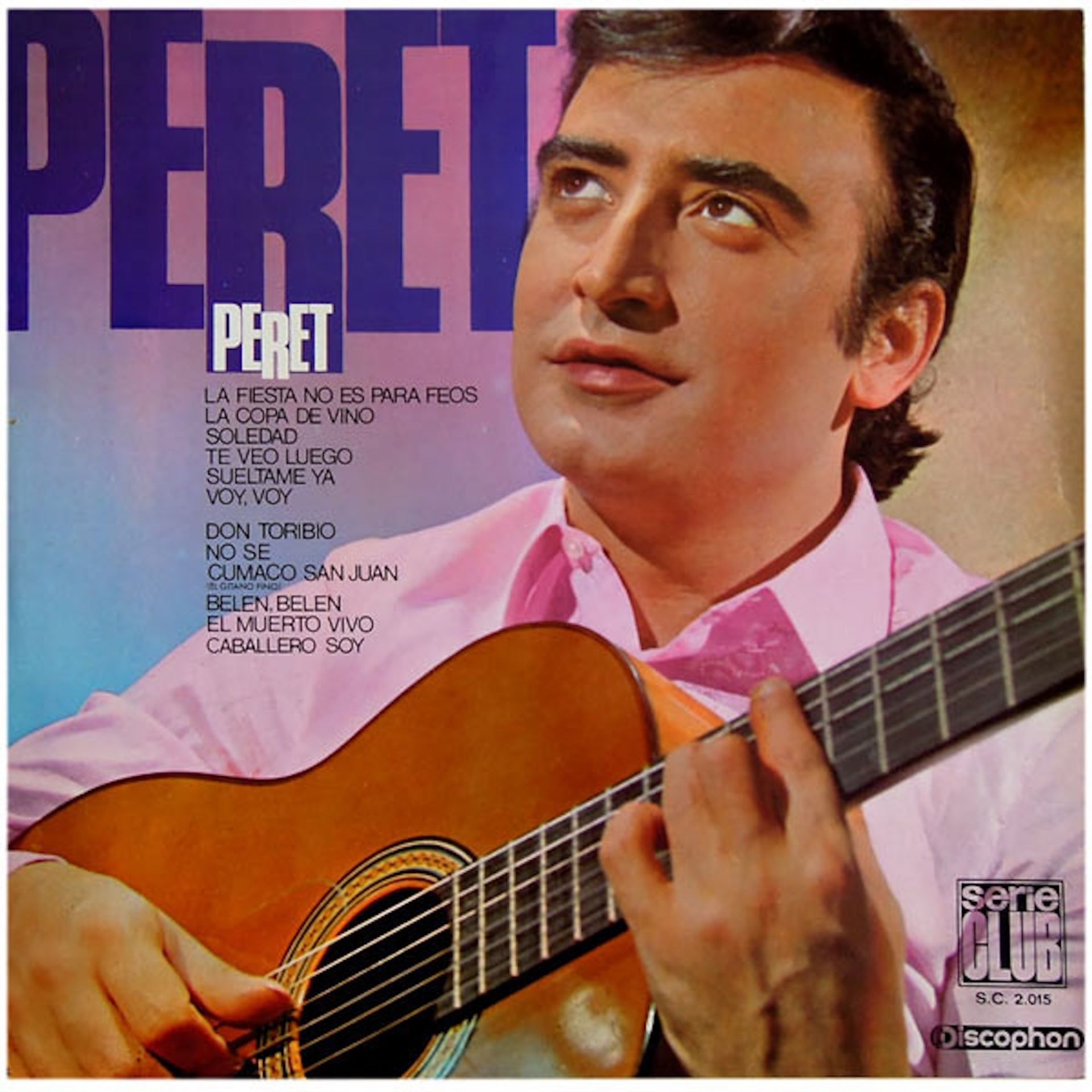

Track 02: Peret, El Muerto Vivo (1965)

“..no estaba muerto, estaba tomando cañas.”

(he was not dead, he was out drinking beers).

Peret’s El Muerto Vivo is not just a rollicking tune about confusing a drunk with the dead. It’s an index of a different kind of urbanism – patchy, fragmented, and dissonant – emerging against the totalising designs of Franco’s regime. While Francoist desarrollismo promised a modern Spain through highways, mass housing and tourist enclaves, this “economic miracle” was, as Paul Preston observes, a kleptocratic modernisation: prosperity funneled to technocrats, generals, the Church and the dictator’s inner circle. Corruption and clientelism shaped the urban landscape as much as concrete and bricks. It was also a project of erasure, of flattening informal neighborhoods, displacing Romani and working-class communities, and branding the country as a sanitised playground for foreigners.

"Peret’s music came from the very centre of dispossession the regime sought to suppress."

Peret’s music, however, came from the very centre of dispossession the regime sought to suppress. Emerging from Barcelona’s Romani community in Mataró and rooted in neighbourhoods like Gràcia and El Raval, Peret’s rumba drew life from spaces described as “problems”: self-built houses, migrant districts, derelict quarters. The origins of rumba catalana are rooted in mixture and continuous exchanges, weaving together Afro-Caribbean rhythms, North African, and Roma traditions. As Silvia Martínez García notes, Rumba Catalana is inseparable from gitanería — a Romani presence that unsettled the regime’s fantasy of a homogeneous, orderly Spain. Its rhythms carved out micro-territories. These were not masterplans but fragments of collective life, spreading unevenly across urban and rural areas. In their very patchiness, they resisted Francoist logics of eugenics and homogenisation.

"Rumba Catalana is inseparable from gitanería – a Romani presence that unsettled the regime’s fantasy of a homogeneous, orderly Spain. Its rhythms carved out micro-territories."

Law was one of the dictatorship’s most effective instruments of control. Roma communities were criminalised under the Ley de Vagos y Maleantes (Law of Vagrants and Delinquents), which Franco tightened in 1954 to expand police authority over anyone deemed “antisocial.” The Reglamento de la Guardia Civil (Regulations of the Civil Guard, 1943) explicitly instructed “scrupulous surveillance” of Roma, authorising identity checks, restrictions on movement, and arbitrary detention. In 1970, the Ley de Peligrosidad y Rehabilitación Social (Law of Social Danger and Rehabilitation) replaced Vagos y Maleantes but kept its punitive essence, rebranding criminalisation as “rehabilitation.” These frameworks — together with municipal housing schemes that relegated Roma families to shantytowns (barraquismo) — made legal equality a fiction. Only the 1978 Constitution and Catalonia’s 2007 recognition of Roma persecution began to redress this history, though its effects remain inscribed in Spain’s cities.

María González Pendás has shown that Franco’s desarrollismo was never a neutral modernisation, but an alliance of technocracy, Catholicism and authoritarian power. The highways, housing blocks, and tourist resorts that advertised progress masked repression, displacing communities while projecting an image of order. In her account, architecture became an “aesthetic of silence,” a technocratic language that concealed violence and exclusion. The Church was not an opponent but an active partner, embedding notions of Hispanidad into modernist form, sometimes using gitaneria (flamenco in particular) in a sanitised version of national folklore.

Franco’s cultural machine sought a similar standardisation. Flamenco was converted into a tourist spectacle, a folkloric Spain emptied of dissent. Alicia Navarro has shown how this process hollowed out flamenco’s embodied histories of pain. Rumba, by contrast, was too quotidian, too unruly to be monumentalised. In this sense, El Muerto Vivo stages a refusal. Its refrain — “No estaba muerto, estaba de parranda” — is a declaration of survival: those written off as socially dead by authoritarian modernism were still alive, sustaining themselves through parranda — in other words, partying through.

As Saidiya Hartman points out, archives are structured by domination, thus testimony, memory, and everyday performance become alternative records. Roma life stories, like Peret’s rumba, tell a history that official documents suppress. Pedro G. Romero similarly reminds us that flamenco and rumba are machines that generate history outside the archive, through embodied repertoires of sound. Where Francoist urbanism aimed for fascist order and uniformity, rumba created dispersed and fragmentary spaces: thresholds open to the street, rhythms drifting into everyday life. This was not a totalising urbanism but a patchwork of interruptions.

"Where Francoist urbanism aimed for fascist order and uniformity, rumba created dispersed and fragmentary spaces: thresholds open to the street, rhythms drifting into everyday life."

Peret’s song conceals a radical spatial proposition. It affirms life in the very neighborhoods marked for demolition, reminding us that statistics — GDP, tourist numbers, cubic meters of concrete — cannot measure the survival of communities. El Muerto Vivo is not only a song but an urban practice, mapping a Barcelona that refused erasure. Against Franco’s grids, it offered disorder, and counter architecture. Against silence, noise. Against necropolitics, parranda: not dead, but always out, dancing, drinking, living…

"'El Muerto Vivo' is not only a song but an urban practice, mapping a Barcelona that refused erasure."

Peret, Peret LP (1967), Discophon. Sleeve art by Fotocolor/Pérez De León.

You can listen to the featured songs and the rest of the Sonic Kinships soundtrack [here].

Bio

Ivan L. Munuera is a New York-based scholar, critic, and curator working at the intersection of culture, technology, politics, and bodily practices in the modern period and on the global stage. He is an Assistant Professor at Bard College; his research has been generously sponsored by the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies and the Canadian Centre for Architecture. In 2020, Munuera was awarded the Harold W. Dodds Fellowship at Princeton University. Munuera has presented his work at various conferences and academic forums, from the Society of Architectural Historians and the European Architectural History Network to Columbia GSAPP, Princeton University, Het Nieuwe Instituut, CIVA Brussels and ETSAM, among many others. He has also published widely, from the Journal for Architectural Education (JAE), The Architect’s Newspaper to Log and e-flux.