01. HouseEurope! A poetic prompt

When form endures beyond its intention, a new condition begins.

Stability frays into possibility; permanence becomes rehearsal.

Readying to chance upon a collective orientation,

subsumed through proximation,

an open invitation us to listen more closely to existence,

to all that is embedded in structure.

What it means to belong unfolds in configuration:

to adopt life is to adapt symbioses,

to inhabit includes accepting that permanence is always already reused.

Collectivity is a choreography of roots, reciprocity, relation: the contexts of matter.

Places made to

become ready

again

and again

02. KoozArch to Charlotte Malterre Barthes How do you define the ready-made?

Charlotte Maltherre Barthes “It’s already there, but not innocently so. The raw matter it is made of — oil, iron ore, timber, sand, whatever — has been ripped from the earth or chopped down, leaving a gaping hole; that matter has then been crushed, heated up to 1450°, pressed, annealed, or dipped in formaldehyde, bent, shaped, moulded or poured into that ‘usable’ form we want it to take. It has already overspent its carbon credit. And now it’s there.”

03. Charlotte Malterre Barthes to Mariam Issoufou Architects How to contend with this harm?

Mariam Issoufou Architects “While ready-made might prioritise something that is already there — which, in coming into being, unfortunately harms its environment — an additional side-effect is a commodification of objects and buildings that encourages us to discard what exists in order to perpetually make way for what is new. This is a stark departure from our building processes historically, where "what is already there" is something that is already venerated by use and can find a new life. Contending with the harm of the ready-made must also allow questioning the idea of production for relentless consumption. We must be able to re-ingest the ready-made, inherently conceptualising it for multiple lifecycles.”

The mission of Mariam Issoufou Architects, founded by Nigerien architect Mariam Issoufou (centre), is to create sustainable architecture rooted in Niger’s cultural heritage, addressing social and environmental challenges.

04.Mariam Issoufou Architects to Natura Futura Is sustainability compatible with the idea of the ready-made?

Natura Futura “From our position in the Global South, ‘sustainability’ has often been altered by market logics and aesthetics that do not respond to our local realities. The ready-made, when extracted from its original context and reinserted as a design or art object, can reproduce those same logics of commodification. In our territories, reuse has never been a trend — it has been a necessity, a form of survival, and a way to reevaluate what is ours. True sustainability lies in territorial memory and collective action, not in objects alone. Every object needs its context to be what it is.

We believe the most pressing issue is the transformation of popular and vernacular elements into luxury commodities, stripped of their communal meanings. If the ready-made is to be truly sustainable, it must abandon spectacle and become a driver of awareness: not curated, but collectively re-signified; not sold, but shared. Otherwise, it risks becoming yet another recycled symbol without context.”

Community Productive Development Center supporting female weavers by Juan Carlos Bamba, Natura Futura Arquitectura in Las Tejedoras located on the outskirts of the urban community of Chongón, Ecuador.

05. Natura Futura to TAKK In contexts where communities resist displacement and political neglect, can architecture truly act as a generator of collective awareness? If so, why does most architectural production still look outward instead of toward its own communities?

TAKK “Architectural production is deeply tied to capitalist economic imperatives. Extractivism, dependence on fossil fuels, and housing speculation have made Architecture and the market a perfect duo for driving the economic growth of a privileged few at the expense of others, deepening inequalities across geographies. Only when architectural practice frees itself from being a market-driven enterprise can it truly strengthen communities and foster political transformation. We call for an architecture that stands in defense of its commons: not only shared physical resources such as land, water and housing, but also collective knowledge, cultural heritage, and ecological systems. These resources — and access to housing itself — must be recognised as rights. It is an architecture centered on care and reciprocity, rooted in mutualism rather than competition, building resilience and solidarity instead of perpetuating extraction and inequality. It is also an architecture that defends environmental interests, engaging with the struggles of other species.”

Laboratory of Future Tarragona Multidisciplinary Session in the Framework of Water Parliaments, the Catalan Participation at the Venice Biennial 2025

TAKK to Syn The challenges posed by the multiple crises arising from climate change require a systemic rethinking of architecture and beyond. How essential is it to dismantle disciplinary boundaries and work through deeply integrated, multidisciplinary approaches?

Syn “From the perspective of collective responsibility, dismantling disciplinary boundaries is essential because climate change is not only a technical challenge but also a social and cultural one. Architecture must operate as part of a shared project where designers, practitioners, policymakers, and communities co-produce knowledge and solutions. A collective lens shifts the focus from isolated expertise to integrated practices that acknowledge the interdependence of humans, ecosystems, and infrastructures. Working in this way allows architecture to become an agent of systemic change, aligning design with justice, resilience, and planetary care. In facing climate crises, it is only through deeply collaborative and multidisciplinary approaches that we can reimagine built environments as collective, regenerative acts rather than individual statements.”

Sara Alissa and Nojoud Alsudairi, Invisible Possibilities, When the Earth Began to Look at Itself, Desert X AlUla 2024, photo by Lance Gerber, courtesy of The Royal Commission for AlUla.

07. Syn to Estúdio Flume If architecture is approached as a practice of care across disciplines, communities, and ecosystems, what methodologies would you propose to foster new forms of collective agency and resilience?

Estúdio Flume “Architecture can be a unifying agent for solutions across different disciplines, communities and ecosystems, starting with the transformation of the architect from an author into a facilitator. This transformation can be experienced through collaborative methodologies that share the lead role in projects with communities such as co-creation processes, as well as through social cartography, which maps local histories, traditions, and knowledge. The integration of different types of knowledge, technical, traditional, and local, naturally creates hybrid solutions that strengthen cooperation and autonomy, resulting in resilient and balanced socio-spatial ecosystems.”

In Sumaúma Village, 35 kilometers from the nearest urban core, the municipality of Vitória do Mearim, in the state of Maranhão, Brazil, is this workspace for babassu coconut harvesters, a project of Estudio Flume, the São Paulo practice of Noelia Monteiro and Christian Teshirogi.

Estudio Flume to Atelier Fanelsa Related to your position on working with regenerative materials, how do you balance on-site experimentation with the demands of project execution, in terms of reconnecting with traditional techniques and methods?

Atelier Fanelsa “Prototyping is an important method when working with regenerative materials. First prototypes are small-scale and created by our team in our workshop. Then we include craftsmen to construct full-scale 1:1 prototypes on site. These serve as a visual reference and form of communication with our clients. In our village, we initiate projects ourselves, where we are able to pursue the most experimentation. Private clients and cooperatives are open to integrating bioregional materials, as we always work in an existing building. Our public clients demand the highest reliability from us, during the early design phases we already need to decide on each material and prove that it is possible to execute them.”

As part of the seminar “Rural Resources” from the Technical University in Munich, participants gathered in Gerswalde, Brandenburg where the ruins of a historic half-timbered building provided the setting for practical investigations into regenerative building practices. The students received input from Professor Niklas Fanelsa, Christian Gäth and Micha Kretschmann from the Bauhaus Earth Innovation Lab, and Dr. Agnieszka Polkowska from the Arts Academy in Szczecin who led the students in ethnographic mapping and “deep mapping” of the local soils from a social, scientific, and spatial perspective.

09. Atelier Fanelsa to Wallmakers What role does craftsmanship play in your work? Do you always collaborate with the same craftsmen or do you assemble changing teams? At which point in the design process do you involve them?

Wallmakers “The answer to this question involves defining the word “craftsman”. A craftsman is someone who skilfully constructs/ builds the traditional way with great precision and intent. As traditional ways are becoming more and more irrelevant in the modern era, as an architect my thoughts include trying to learn the craft in every possible way. In this sense the craftsman often becomes the teacher and I find myself as the “student”.

As time goes on, we start to understand a bit more about this process ushering in a new way. These new “craft” methods, which deviate slightly from traditional practices, adapt to the modern requirements and environment. Therefore, design is definitely an outcome of materiality, site, requirements and traditional crafts.”

Plastic has managed to snake its way into almost every aspect of our daily lives, including 90% of the world’s toys, which is a far cry from the old Indian childhoods of outdoor play and wooden toys. When a project came up in Vadakara, North Kerala where the consumption of toys is the most in the state, the idea was to have a circular home accessible from every side with a verandah supported by toys and old Mangalore tiles.

10. Wallmakers to Ruth Lang As pollution and waste are a major concern for every sentient being, how can practitioners accommodate the present and future dilemmas into their designs?

Ruth Lang “We need to be more conscious of the entanglements with waste that processes we enact through our designs. These effects are often remote and unseen, but have tangible impact on other systems and times beyond our own. We need to stop deifying the sanitised, utopian vision of architecture, and embrace the dirty reality of its creation. It’s no longer reasonable to privilege the consumption of virgin materials, whilst seeing reuse and transformation as a lesser, constrained practice. Instead, we must reframe our relationship with what we consider to be waste, placing as much importance on the afterlives of what’s cast aside in processes of production as the end output. By situating imperfection and transformation more centrally to productive practices, we open up new opportunities for creativity, as well as minimising harm. It’s a process that values serendipity and listening over control, and leads us into unexpected territories as a result.”

11. Ruth Lang to Architects for Gaza When we consider rebuilding after conflict and disaster, what systemic processes - beyond the tangible projects and programmes that we design - might we put in place that can offer long-term and wider reaching opportunities for future resilience?

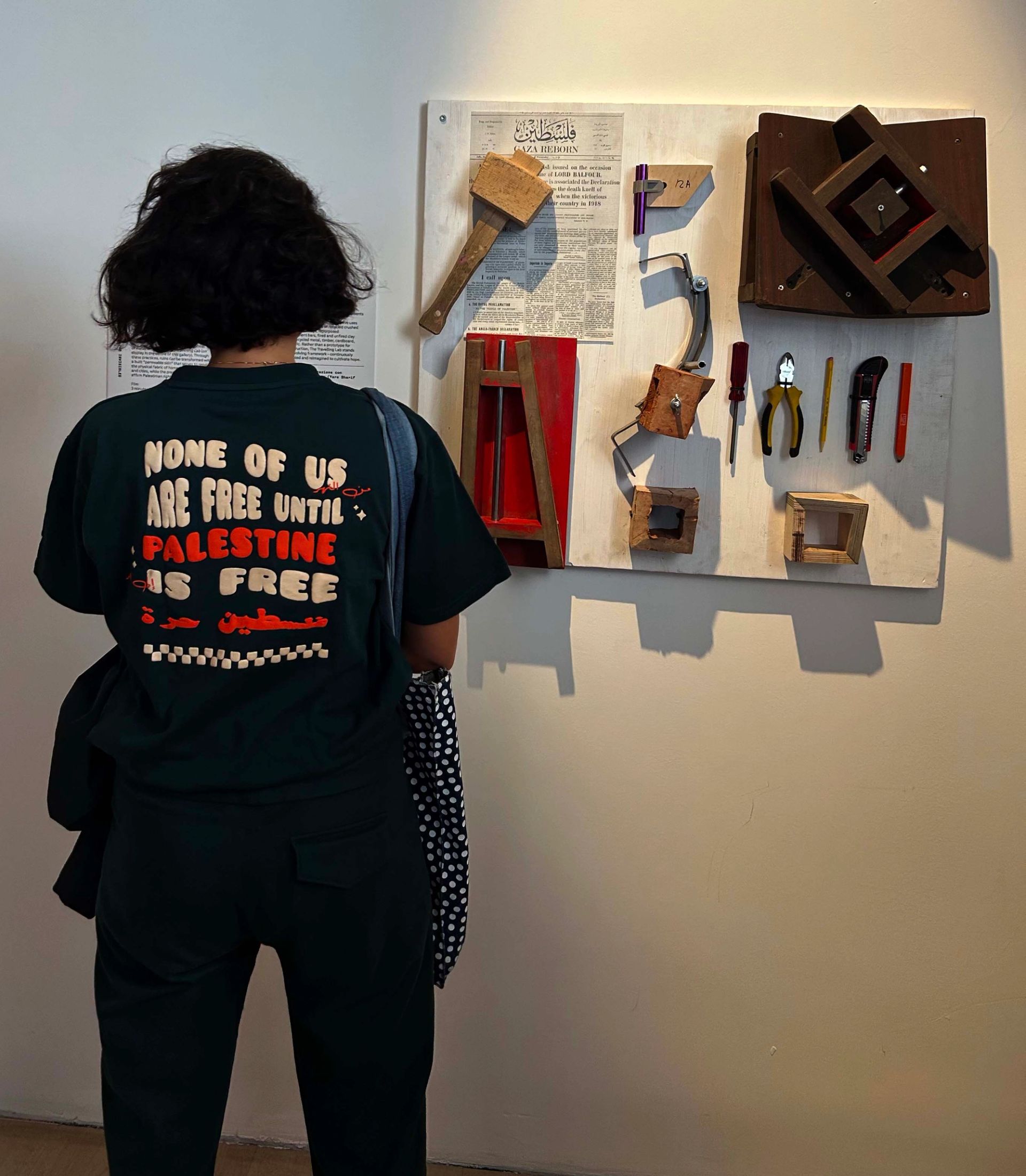

Architects for Gaza “Resilience is often described as the ability to bounce back, yet in architecture it demands more than adaptation; it requires agency. In contexts where colonisation and occupation persist, such as Palestine, resilience must empower local communities to shape their own spaces. What does healing mean in a scarred landscape? These concerns should precede programmatic or formal design, raising urgent ethical questions before architectural solutions take form.

Memory, repair, and the reconstruction of the intangible must guide the process, ensuring it is free from colonial traces. For this, architects must step back, creating conditions for local people to lead. Unlike in neoliberal contexts — where “repair” suggests resolution — here, rebuilding must remain attentive to the ongoing crisis.

Resilience, then, is a difficult notion. To approach it, architecture must take a critical stance: narrating the past, engaging with ruins, marking the present, questioning who builds, and asking whether reconstruction offers only short-term relief or can open a pathway to long-term justice and empowerment.”

As a collective of architects, designers, and professionals in the built environment from Palestine and across the globe Architects for Gaza focus our capacities and marshal our professional energies towards a bold and free future for Gaza and Palestine as a whole.

12. Architects for Gaza to Organizmo What lessons can we learn from your unique practice and work when rethinking Gaza, reconstruction and rebuilding the community? How to deal with the scarred landscape?

Organizmo “We see and practice architecture as a fabric of possibilities to re-weave with all forms of interconnectivities of care; to shelter all interactions that make visible the exciting breath of life and all possible forms to honour and recover our collective dynamics.

From our idea of Arquitectura Propia (Own Architecture), constructions are not imposed on the land: they arise from a dialogue between the territory, the community and the spirit of the place — embodying autonomy, reciprocity, and dignity. We conceive architecture as a regenerative and pedagogical process where each stage — from site selection to material selection — is an opportunity to repair links between communities, ecosystems and memories.

The process of rebuilding Gaza should not be about restoring structures as an objective, but as a result of supporting collective weaving of solidarity economies that restore sovereignty to communities. It is about cooperative planning in which decisions are made from the territory and for the territory’s reality — acknowledging that today’s notion of territory is rooted more in a culture of collective imaginaries and cosmovision than in a physical landscape.

Rebuilding Gaza should not be an exercise of replacement, but a process of listening, accompaniment and collective regeneration. The scar thus becomes a teacher, reminding us that new forms of life can also spring from the fracture.”

Pioneering educators in low-impact construction techniques, alternative technologies, and ecological restoration in Colombia, Organizmo has worked with different communities across Latin America to develop sustainable habitats and new modes of artistic and cultural expression. Pictured: the Casa de Piensamento in the rural Colombian community of Tenjo, Cundinamarca.

Bios (A-Z practice name)

Architects for Gaza is an initiative founded by Yara Sharif and Nasser Golzari, UK-based architects and academics whose work challenges dominant architectural paradigms. Sharif explores design as a tool to rethink contested landscapes, advocating for an alternative, inclusive architectural and spatial language. Golzari calls for architectural approaches that challenge Western dominance, drawing inspiration from the daily rituals, narratives, and passive environmental practices of the Global South. Together, they co-founded the Palestine Regeneration Team (PART) and more recently, the initiative AFG, bringing together architects, educators, planners, environmentalists, and designers to respond to the ongoing spaciocide in Gaza. Their work has received numerous accolades, including the RIBA President’s Award for Research and the Holcim Award for Sustainable Construction in the MENA region.

Atelier Fanelsa, founded by Niklas Fanelsa, is an international team of architects based in Berlin and Gerswalde (Brandenburg). The studio investigates contemporary forms of working, living and commoning in the countryside, the periphery, and the city. We realise private projects, public buildings, exhibitions, and workshops. Within these formats we develop innovative and qualitative answers to questions regarding the conditions of today’s society. Atelier Fanelsa was founded in 2016 by Nick Fanelsa.

Mariam Issoufou Architects, founded by Mariam Issoufou Kamara in 2014, is an architecture and research practice addressing public, cultural, residential, commercial and urban design projects from their offices in Niamey, New York and Zurich. Issoufou’s design explorations are informed by rigorous research and a process rooted in conversations with end-users and collaboration with local crafters, masons and builders. The firm’s completed projects in Niger include Dandaji Regional Market, the Hikma Community Complex — awarded two LafargeHolcim Awards for sustainable architecture — and Niamey 2000, shortlisted for 2022 Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

Charlotte Malterre-Barthes is an architect, urban designer, and Assistant Professor of Architectural and Urban Design at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), where she leads the laboratory RIOT.She was previously Assistant Professor of Urban Design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, from where she launched in 2021 the initiative 'A Global Moratorium on New Construction' (A Moratorium on New Construction, Sternberg Press/MIT Press, 2025), interrogating current protocols of development and urging for profound reform of planning disciplines to face the climate and social emergency.

Estudio Flume, founded by Noelia Monteiro and Christian Teshirogi, is an architectural office based in São Paulo, develops socio-environmental projects in remote areas of Brazil, working across diverse biomes on a country of continental scale. Each project provides an opportunity to learn about local geographies, climates, and productive activities. These projects aim to protect traditional communities that preserve the Amazon rainforest. In each case, the focus is on the learning process before and during construction, highlighting the spatialisation of community needs and the sustainable use of resources. This year, Estudio Flume won the Simon Prize, curated by the Fundació Mies van der Rohe in Barcelona.

HouseEurope! is a registered non-profit organisation conceived as a policy lab dedicated to shaping legislation and hosting the European Citizens' Initiative (ECI). The HE! team and approach originates from the architecture practice bplus.xyz, focusing on how to use legislation to adapt and reuse existing buildings, and the chair for architecture and storytelling station.plus, focusing on how to use time-based media to design the advent of an idea into culture.

Natura Futura, founded by José Fernando Gómez Marmolejo in 2015 in Babahoyo, Ecuador, explores community-based and public projects, issues and themes within a Latin American context. The studio considers it vitally important to work with contextual architecture: interpreting the site without forgetting the human context of these projects, and understanding the emotional component of its inhabitants, their traditions and customs. The studio held exhibitions at architecture festivals in Bali, Indonesia and Valparaíso. The studio has been recognised with awards at the Quito Pan-American Biennial, receiving three Quito Biennial awards in 2020, and more recently at the Brick Awards in Vienna in 2022.

Organizmo is both a regenerating forest and a training and research centre located near Bogotá, Colombia. It is dedicated to weaving intercultural processes and pedagogies to reconnect body, territory and community, based on the convergence between ancestral knowledge and contemporary practices. Organizmo's infrastructures not only house bodies, but also take care of the relationships between them and with the planet. These spaces function as architectures of care, symbolic and restorative areas where deep listening practices are exercised, interdependence is experienced and processes of collective harmonisation are generated.

Dr Ruth Lang is an architect, researcher, writer, and MArch programme director at the London School of Architecture. She has worked with the Design Museum’s Future Observatory, and is the author of Building For Change: The Architecture of Creative Reuse (Gestalten, 2022). Throughout her work lies an interest in the networks and mechanisms of architectural practice, exploring the changes through which we might achieve a more equitable profession.

StudioTAKK, led by Mireia Luzárraga and Alejandro Muiño, is an architecture and research studio based in Barcelona and New York. Their work integrates feminism and ecology to promote fairer living environments. Luzárraga is Assistant Professor at Columbia University GSAPP in New York, and both are visiting professors at the University of Tokyo. They have received awards such as "Design Vanguard 2024" and "FAD 2023" and their work is featured in collections including the FRAC Centre, Vitra Design Museum, and DHub Barcelona.

Syn is a Riyadh based practice founded by Saudi architects Sara Alissa & Nojoud Alsudairi. The practice focuses on ecologically sensitive architectural design that derives its aesthetics from a contextual awareness of nature and expresses the essence of the materials from where they are found. In addition to syn, they have established the Um Slaim collective, a critical investigation of the displacement of vernacular Najdi architecture in the area of central Riyadh. They are also the co-founders of SaudiArachitecture.org, an independent organisation that aims to research and archive modernist and post-modernist buildings in Saudi Arabia.

Wallmakers, founded by Vinu Daniels, is a practice dedicated to the cause of sustainable and cost-effective architecture. Amidst the current Global climate crisis, it becomes all the more important to substitute the question of "What should we build?" with "Should we build?". And in facing the question of where we must build, the need to use materials that have already become an environmental hazard in the place of fresh material has become the need of the hour. Wallmakers uses waste materials to research and develop new construction techniques to build sustainable spaces that are responsive to specific site contexts and conditions, while maintaining a balance between innovative, utilitarian designs and creating contextual dream-like spaces.