Raymond Williams described "structures of feeling": emergent moods that register before they harden into doctrine.1 Publishing, especially in fugitive forms, is such a register. A zine read aloud to a friend becomes a social event; an annotation penciled in haste may outlast the exhibition itself. On a recent afternoon, I watched a visitor linger over a slim issue of Deem Journal, scribbling in her own notebook, while another flipped quickly through pamphlets of speculative housing schemes. Their postures spoke volumes: attention stretched, curiosity alive, connections forming across titles. To witness reading here is to see Williams's concept literalized, structures of feeling made visible as collective practice.

To step into the Reading Room at the MAK Center is to enter an argument staged in space. Installed within architect R.M. Schindler's Kings Road House, the exhibition unfolds less like a gallery than a rehearsal studio. Light pools on tables scattered with journals and pamphlets, zines and artist books. Readers lean over spines and margins, their postures echoing the pitched diagonals of Schindler's planes. This is no mausoleum of publications but rather a site alive with rustling paper, penciled annotations, the half-audible murmur of someone reading aloud to a friend. Books here are not props. They are devices, each one activating another line in a distributed conversation.

"This is no mausoleum of publications but rather a site alive with rustling paper, penciled annotations, the half-audible murmur of someone reading aloud to a friend."

The curatorial team — Beth Stryker and Robert J. Kett, alongside commissioned furniture by Ryan Preciado, and Mimi Zeiger’s table residency restaging the Table for Reading — position the printed page as an architectural medium. No neat models or polished renderings, no vitrines demanding reverence. Instead, the room itself behaves as an epistemic infrastructure: a network of surfaces and gestures, a choreography of attention that makes discourse tangible. To call it an exhibition feels misleading; it is in fact closer to a switchboard.

The spatiality of Schindler's early-twentieth century private home amplifies the effect. Built as an experiment in cooperative living, Kings Road blurred thresholds between private and public, intimate and civic. Pauline Schindler cultivated the place as a salon, where conversations spilled across sliding partitions, where music, meals, and manifestos coexisted. To install a reading room here is to tap into that genealogy of the provisional community. The architecture itself models what Rosalind Krauss 2 once named the "expanded field": meaning produced not by a fixed center but through adjacency and relation, the contingent logic of "and/also" rather than "either/or."

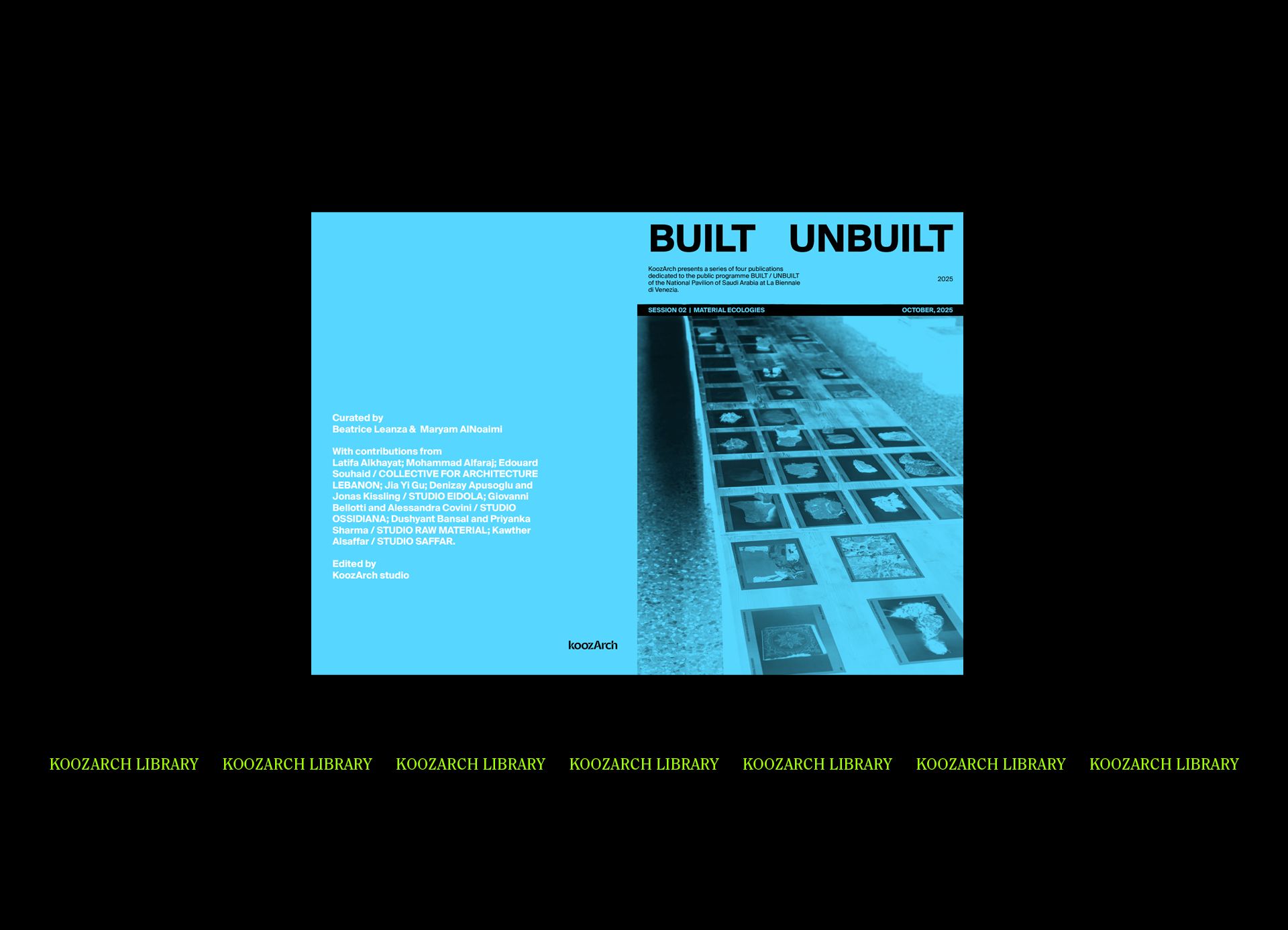

Installation view of Reading Room MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House, June 5, 2025 – September 14, 2025. Photos by Joshua Schaedel / MAK Center for Art and Architecture. Featuring Furniture for Reading by Ryan Preciado: Library Lounge Chair, Plywood, beech veneer and upholstery; 2025. Copyright © Ryan Preciado. Courtesy the artist and Karma. (Pauline Schindler Studio)

The Reading Room also belongs to the tradition Felicity Scott has called the “counter-institutional fragile” — provisional practices that unsettle hierarchies yet persist as generative forms.3 Neither fully inside the museum system nor outside it, the room suspends itself in a para-institutional position. If, as Krauss has argued, modern disciplines articulate themselves across an expanded field 4, Schindler's house is an early Los Angeles instance of architecture expanding into domestic sociability, informal publishing, and the work of reading itself.5 Its furniture tells the story: a long communal surface dubbed the Table for Reading; low carts stacked with stapled pamphlets, shelves mixing glossy journals with hand-bound zines. Nothing is precious; pages can be touched, dog-eared, shuffled. The scenography exposes its scaffolding the way a bibliography reveals its provisional logic. Visitors become participants; handling and annotation are folded back into the exhibition itself.

The stakes are clear. What happens when publishing refuses hierarchy? A lavish artist's book beside a photocopied broadside collapses distinctions between canon and ephemera. Hierarchies of medium dissolve into adjacency, and adjacency itself becomes a political method. This method unsettles the canonical history of architectural publishing. The Reading Room's shelves enact this expanded historiography. Alongside design journals are works from small presses - Apogee Graphics and All Night Menu - the familiar arc runs from modernist manifestos to the little magazines stitching vernacular memory. Magazines like Deem Journal, loud paper, and Los Angeles Review of Architecture (LARA) frame design as civic practice. X Artists’ Books, Semiotext(e), Inventory Press, The Fulcrum Press, Atelier Éditions and Marta.LA insist publishing is itself spatial politics. Each entry thickens the record, reminding us that discourse is always contested terrain, its margins as important as its centers. Whose histories are legible? Whose voices remain missing? The Reading Room does not answer so much as stage the question.

"Hierarchies of medium dissolve into adjacency, and adjacency itself becomes a political method. This method unsettles the canonical history of architectural publishing."

Publishing is labour, and not only intellectual. It is also a labour of care. To bind pages, choose type and spacing, stitch or staple, these are forms of attention to how ideas live in the world. Care is political.

Feminist and decolonial scholars remind us that citation is an act of recognition, an infrastructure of acknowledgement that either perpetuates exclusions or repairs them. A bibliography is never neutral; it draws a map of who counts. In the Reading Room, this politics is palpable. To place an Indigenous zine beside an influential modernist journal is to redistribute visibility. To foreground a small-press imprint alongside an academic quarterly is to ask what forms of authority publishing sustains. Layout becomes ethics, adjacency and practice of repair.

Installation view of Reading Room, MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House, June 5, 2025 – September 14, 2025. Photography by Joshua Schaedel / MAK Center for Art and Architecture. (Clyde Chace Studio)

One curator monitoring the room described how often visitors returned, sometimes with friends, sometimes alone, drawn less by any single text than by the chance of encounter. "It's not about completeness," she said. "It's about relations." Her phrasing echoed Krauss but her tone suggested something more intimate: a care for how readers, texts, and spaces hold one another in tension.

This care matters in a contemporary ecology of attention increasingly defined by extraction. Today discourse circulates in an environment of disinformation, digital overload, and algorithmic acceleration. In this context, publishing risks becoming just another commodity stream. The Reading Room offers a counter-model: slow, embodied engagement. Reading here is weight in the hand, the smell of ink, the sound of pages turning. The temporality is slower, the bandwidth narrower, but the intensity greater. It recalls an ecological ethic: not extraction but stewardship, not acceleration but repair.

Publishing is of course material — paper, ink, glue, distribution — but also ecological in a broader sense: tending memory and debate, sustaining a cultural commons. In this way the Reading Room mirrors urban politics, where the question is not simply growth but care, not permanence but renewal. James C. Scott would call these gestures "hidden transcripts": low, everyday practices through which publics craft vernacular counter-narratives alongside official ones.6 To read together is to institute another public, authoring networks that need no canonical sanction.

Reinhold Martin reminds us that systems are habits embedded in workflows; publishing is such a system.7 Trade journals, little magazines, institutional reviews, artist books: all shape what can be said, who hears it, how quickly discourse calcifies. The Reading Room tweaks that system: pull a zine, annotate a margin, leave a note. These micro-protocols create another infrastructure, one valuing slowness, adjacency, and return. Just as cities must reckon with unsustainable expansion, so must publishing reconsider its modes of circulation. What endures is not necessarily what sells, but what is sustained, cared for, returned to.

"Just as cities must reckon with unsustainable expansion, so must publishing reconsider its modes of circulation. What endures is not necessarily what sells, but what is sustained, cared for, returned to."

Which brings us to a speculative horizon: what might publishing become if understood as civic infrastructure? Not simply a disciplinary artifact but a shared system for producing publics. The Reading Room offers one rehearsal. It generates architectures of relation through adjacency, one pamphlet beside another, one reader beside another. And it gestures to a longer lineage: manuscript libraries in the Islamic world circulating texts hand to hand; Latin American collectives sustaining radical presses under dictatorship; African small presses forging postcolonial literatures. Each is precedent for publishing as infrastructure: organizing publics without walls or gates.

Circulation path Reading Room, MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House, June 5, 2025 – September 14, 2025. Floor Plan. Courtesy of Friends of the Schindler House, MAK Center | Copyright © MIIM Designs.

To sit at Ryan Preciado’s Table for Reading, designed for the the Reading Room exhibition within Schindler's Kings Road House | MAK Center is to glimpse architecture's endurance relocated from monument to medium. The claim is modest yet urgent: that the infrastructures of thought we build, bibliographies, periodicals, annotated margins, may prove more durable than concrete or steel. In a time when publics are fractured and attention commodified, the Reading Room reminds us that publishing remains one of architecture's most exacting crafts: a civic technology for keeping disciplines porous and democracy alive.

"The claim is modest yet urgent: that the infrastructures of thought we build, bibliographies, periodicals, annotated margins, may prove more durable than concrete or steel."

Bio

Maryam Eskandari is a designer (architect) and an educator. In 2013, she founded MIIM Designs, a practice dedicated to community engagement, interdisciplinary collaboration and design innovation through the use of local and traditional materials. Under her leadership, MIIM has been a two- time recipient of the National Endowment for the Arts Award, the Doris Duke Foundation Award, National Endowment for the Humanities and the Institute of Library and Museums. Maryam is the 2009-2011 recipient of the Aga Khan Program in Islamic Architecture Award.

Notes

1 Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford University Press, 1977).

2 Rosalind Krauss, "Sculpture in the Expanded Field," October 8 (1979): 30-44.

3 Felicity D. Scott, Outlaw Territories: Environments of Insecurity/Architectures of Counterinsurgency (Zone Books, 2016).

4 Ibid.

5 Kevin Starr, Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990-2003 (Knopf, 2004); Reyner Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (Harper & Row, 1971); Esther McCoy, Five California Architects (Praeger, 1960); Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster (Metropolitan Books, 1998)

6 James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (Yale University Press, 1990).

7 Reinhold Martin, The Organizational Complex: Architecture, Media, and Corporate Space (MITPress, 2003); Beatriz Colomina, “The Exhibition as Architecture,"https://www.textezurkunst.de/en/92/beatriz-colomina-exhibitionist-architecture/