This interview is part of a series of ten conversations exploring OBEL and its initiatives, including the Award, Fellowships and Travel Grants.

Federica Sofia Zambeletti / KOOZ It's a real pleasure to bring the two of you together in conversation for OBEL. Wayne Switzer and I met a few years ago, just before he began his position at The Sitterwerk Foundation in St Gallen, Switzerland, which comprises an incredible library, archive and space of material experimentation. Beatrice Leanza is a writer, cultural producer and curator — most recently, of the Saudi Arabia Pavilion at the current Venice Biennale of Architecture, featuring a fascinating pedagogical experiment undertaken with Syn Architects and The Um Slaim School.

Beatrice, your recent book The New Design Museum (Park Books, 2025), relies on the premise that cultural institutions are essential components of social infrastructure. Could you expand on this a little further?

Beatrice LeanzaThe reason I wrote this book is because I'm a deep believer in the power of cultural institutions as transformational engines, impacting our collective lives. The book, of course, speaks specifically to institutions of design and architecture; this is an important subset to analyse. This notion gestures toward the fact that from the polycrises — enduring globally — within which we find ourselves, we are witnessing a collapse of past world systems; that includes systems of governance, of information, of technological mediation, of life-sustaining supply and distribution, to which we must respond by completely rethinking the way we live on the planet. This systemic reconfiguration is central to the disciplinary ecology of design.

And to follow on from that, when it comes to the processes, ideas, methodologies and ways that we might deploy to collectively deliberate towards a sustainable (whatever that word might mean) future, I find that we are really witnessing an erosion of public spaces or fora where we can encounter each other, and imagine together. We lack the places to debate and collectively prototype, test and build a different outlook for a common future. Institutions of culture — whatever their scale or geographical location — are, for me, social incubators; places for wild dreaming, for prototyping new realities. That's what the book explores.

"We lack the places to debate and collectively prototype, test and build a different outlook for a common future. Institutions of culture — whatever their scale or geographical location — are, for me, social incubators."

KOOZ I love this idea of institutions as transformation engines. So the question is, how must they transform? You mentioned that there are fewer spaces where people can come together. How does an institution offer an alternative and future-facing forum?

BLSo: there are two things that are important to mention here, and knowing a little about what Wayne has been doing, I'm sure that he will concur. First of all, we need to really deconstruct, if not demolish, the idea that there is only one institutional model that trumps all others. Institutions of culture thrive when their diversity is supported, through serving their communities and by finding continuous modes to transform and challenge forms of public engagement. Cultural institutions are porous environments that should be open to the coming together of different forms of knowledge, of ways of thinking, In a mediated and moderated environment; more precisely, they should hold spaces and exchanges that are not overpoliticised, corporatised, or vulnerable to the imperatives of power, taste or entertainment. It is ‘how’ do we actually preserve and secure a diversity of approaches without subscribing to singular metrics of performance assessment. In that sense, it's therefore a question that connects to the ‘why’ — the reasons that determine what stories institutions decide to champion through their programming.

"Cultural institutions are porous environments that should be open to the coming together of different forms of knowledge, of ways of thinking, in a mediated and moderated environment."

KOOZWayne, I'm keen to hear your perspective and experience, especially since you joined the Sitterwerk Foundation — where you engage not only visitors to the collection, but also local residents who are invited to partake in its activities. How have you reframed the programme of your institution to respond to both audiences?

Wayne SwitzerYes. I must first say that I don't come from a background of archival studies or library sciences. When I began my position here at the Sitterwerk, I was a bit intimidated by the sheer weight of this history, of the many approaches to archiving; I come from a much more applied, practical background of architecture, teaching and research. So I was relieved and happily surprised when I realised that this is actually not just a place of archiving, but more about activating materials and content — even, to go back to a beautiful phrase that Beatrice used, collective deliberation. This is something that we encounter every day here, because yes, the Sitterwerk is an archive: we have over 2500 materials, but these are unlike any materials library that you might find in an architectural or design office. Rather, these are materials in their raw states and often in very atypical formations.

What we have here is a collection that exists in a state of free association. Objects and materials allow themselves to be associated with other forms of content, be it other materials, books or artworks. Rather than imposing specific categories, or telling our users where to look, we allow them first to encounter the material on their own terms. After that, they can dig deeper and deeper, finding various associations. They can get deep into the technical properties of materials, if they wish, but we also have developed tools that allow visitors to connect to other researchers who have previously visited the Sitterwerk, and browse through their connections too. All of a sudden, the content that they're looking at takes on exponentially more associations, meanings that they might not otherwise have come across. That is what I think that we offer here.

There are distinct hats that I wear in my role here: on one hand, guiding artists, architects or researchers, to make these connections and on the other, documenting various processes, as we're adjacent to an art foundry here. This is first and foremost, a place of art production; along with curatorial duties, each day can be quite different from another. So it's quite difficult to answer your question, since what I'm doing changes constantly. I like to think of it as supporting this free association of content.

"Rather than imposing specific categories, or telling our users where to look, we allow them first to encounter the material on their own terms. After that, they can dig deeper and deeper, finding various associations."

KOOZ How would you interpret the OBEL Foundation’s theme of the ready-made or extant conditions, in relation to Sitterwerk’s collection? I’m also thinking about things that are being added to the material library, contemporary artefacts and substances that are made from what already exists —

WS At the core of the Sitterwerk project is, as you say, a collection of materials. But more importantly for me, it's actually the accumulation of knowledge and research associated with those materials. The physical collection is rather orthodox: we have materials. They belong in certain categories or drawers, but for the most part, they're unlabeled. We don't apply any sort of label aside from the category. Each object has a catalogue number, and from that, materials are linked into our catalogue, accessing a general description. Again, what's particular to the Sitterwerk is this ability to tap into the ways that a given material was used or explored by other researchers.

For example, if you're looking into aluminum, you would not only find a variety of aluminum samples; you could also access the collections of other researchers, other artists, artworks, applications, and different lines of inquiry. So when we are talking about building or increasing or growing our collection, the physical objects in our collection actually grow slowly. It's not our priority to just accumulate more and more. What does seem to grow — and what I support — are the connections between researchers and how they have used this knowledge. That’s what I think is the most valuable content that we have.

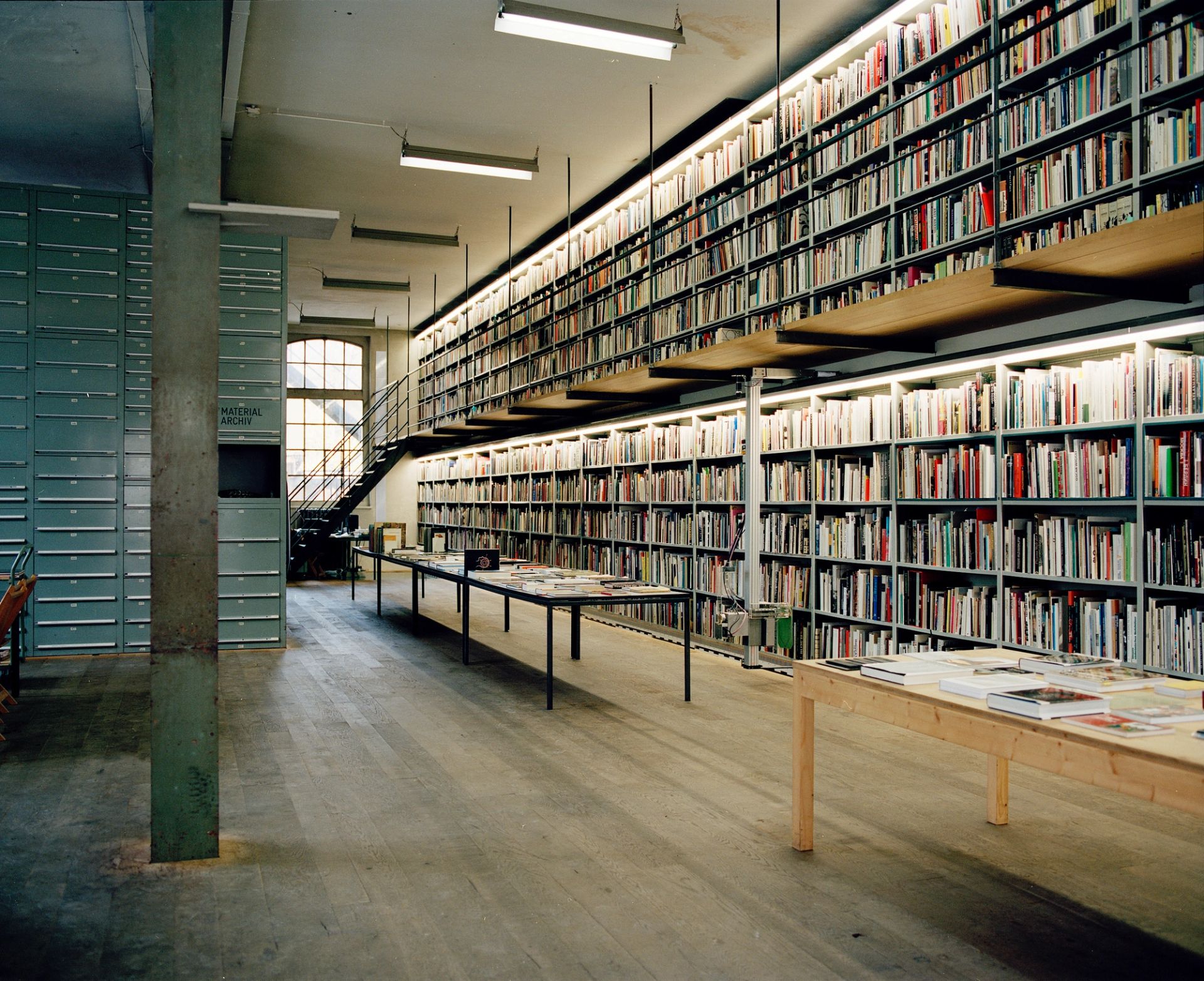

The Sitterwerk Foundation’s Kunstbibliothek is a reference library with around 30,000 volumes on sculpture, architecture, photography, material and casting technology, and material science and restoration.

KOOZ How do you negotiate between that which is a material which is extant rather than something that is newly produced? Do you think about categories like natural and artificial — or, in terms of architectural and construction concerns, are you also interested in materials that have been discarded and are ready to be reused?

WS It's not actually a classification of ours, to describe something as having been made or not. I think we allow that to stay open. As an example, let me take a recent exhibition that we held on sand — it was called Before And After Sand, which we curated with the London-based architecture office Material Cultures. The idea was to take this very ubiquitous material — indeed, something that contemporary life cannot function without — and to expand our understanding of its usage and properties. One could understand this material as something that had a pre existing condition and a condition after a certain need for it has been sated. When you actually look at how we extract and exploit sand, it quickly becomes a very depressing story. Yet most interesting for us is the fact that sand is not even a defined material in itself — it's just a state. It's a condition that a material enters into; it becomes useful in a certain way, and then at some point, it loses those characteristics and is no longer sand. But the category of sand doesn't apply to one specific material composition. Is it ready made if a material has already been one thing and then turns into something else and evolves into yet something else? I'm not sure we would define it, but we do like to pose these questions. We were glad to draw awareness to the fact that this material — which we're using up at an unbelievable rate — was something else prior to that, and can become something afterwards.

KOOZ That's an exhibit I’d like to revisit later in the conversation, particularly in terms of the construction industry and the obvious connection between sand and cement. Staying with the notion of institutional practices and regenerative practices, can you think of instances or other exhibitions where this notion of regeneration has applied also to the museum or institution itself?

"Certain attributes — ecological, regenerative, reparative — are very much a product of our times; the terms themselves have entered into more of a common (design) language."

BL I want to pick up on a few things that Wayne mentioned, especially when speaking of practices within the realm of the built environment: design, architecture and spatial practices at large. Certain attributes — ecological, regenerative, reparative — are very much a product of our times; the terms themselves have entered into more of a common (design) language in the past ten to fifteen years, and their importance has been escalated, in no small part because of the pandemic.

There are two things connected to what institutions can do in this context, and how they would play out. One is the typical role of ‘awareness builders’, which is what we understand [cultural] institutions in general to be. They bring topics into the public and forge certain conversations around them. But this is a dynamic or logic that — unfortunately, in many cases, and particularly since the pandemic — faces great compromise: the choice of topics and the stories are often connected to performance metrics. In a nutshell, it’s about whether the topic is going to sell or not. This is because we work essentially with the one business model, which is substantially driven by ticket sales.

The reality, particularly if we are talking about institutions dedicated to design and architecture, is that we live at a time when the vocation of design itself has changed, and continues to transform. I encounter this in my work as a curator and writer all the time: that design practice is forged at the crossroads of practice, discourse and activism, all positions that are connected with rethinking our relationship to the earth, to the life ecosystems of which we are a part. This change in perspective has moved from the promise and the premise of globalism in the twentieth century; it has now been superseded by a new operative framework, which is that of planetarity. This is where we are steering. Many of the practices that are rooted in this exploration tend to focus on process, methodology, research; they are not running to produce the next shiny object or covetable product. It’s more about the way we get there; the way that we understand and rethink manufacturing processes, the way we research and excavate the histories of materials and environments.

These are facets that align with what Wayne raised, in that (forward-looking) institutions are shifting focus from the physical objects or the collection per se — the value is really in the knowledge that can be produced with it. Of course, this shifts the activities and the agency of the institution dramatically, towards research and development, therefore supporting the production of ideas. It also connects with exploring different fields, rethinking practices of archiving, or the act of collecting itself — it repositions these very traditional activities.

There are definitely more and more exhibitions that have brought such dynamics to the fore. Certainly, perennial events help with that, or at least they speak more loudly to professional publics. We could start with the 2021 exhibition Broken Nature, curated by Paola Antonelli [a collaboration between MoMA and Triennale di Milano] and trace the plethora of events, biennales and discussions that followed on the theme of nature, right up to the current Biennale in Venice. These sorts of exhibitions are concerned with how we tell relevant stories and how we talk about their complex ramifications.

On another note, I would propose that we move away from such categorisations as material knowledge or culture — and start to think through “material ecologies”. It’s a more fitting term, because it unveils the idea of broader histories and associations, of durational processes across geographies, cultures and generations. So when it comes to looking at how such discourses can impact institutional practice, they can certainly help us move away from the urge to grab hold of the latest, newest and potentially short-lived trends.

Hopefully that can encourage [institutions] to stay with stories and issues that matter, that require time and dedication. This goes back to the idea of social impact that institutions can produce. Certainly, I believe the idea that we might start to view museums and cultural institutions as places of entertainment is very dangerous.

"Certainly, I believe the idea that we might start to view museums and cultural institutions as places of entertainment is very dangerous."

KOOZ Wayne, there's a relation to the Sitterwerk here in terms of knowledge production and research prototyping, which is at the heart of the project. We could even take sand as a starting point, or a common ground from which we can discuss the wider experimentation and programming that you've been unfolding in the last year..

WS Yes, I had the feeling that Bea was describing, in some sense, a macrocosm of what we do. Well, the short version is that at the Sitterwerk, we really try, as much as possible, to avoid categorisation; to avoid the inherent hierarchies which exist in archives and in libraries, and to place trust in the user, allowing them to inform our collections. That's how our book library, in particular, works; it's a dynamic order, constantly moving. It's perpetually informed by the user; we develop tools that allow us to find books, without inhibiting the very human instinct to associate and reassemble content in various ways. Our materials collection doesn't work quite as dynamically, largely because we're limited in terms of space and because objects function differently from books — but materials and books are the obvious starting point for many of our exhibitions.

So with the sand exhibition, this was something that we became fascinated with, especially through working with Material Cultures: how can we expand the idea of this material beyond a human-centric perception? How can we think about this substance so that it's not just about how much we're consuming, but rather about how sand has existed far longer than humans have been around, and will exist far longer than humans will be around. What are the unexplored opportunities proposed by sand? Because, in fact, it isn't all bad news: just because sand eventually loses its value for us, doesn't mean that sand is no longer useful. Interesting fact: when we began to look into it, we realised that sand is curiously neither present in our archive, nor in the larger material archives within Switzerland. We are actually part of a platform across ten institutions, and we all share knowledge about materials; this larger network allows a much broader technical and detailed approach to materiality — highly recommended. It's a platform called Material Archiv, and what we realised is that sand was not there, across the board. It has somehow always been avoided. So we took this also as an opportunity to investigate this material, generate samples as well. We realised that although we didn't have sand, we all had dozens and dozens of materials which were sand-based. All of a sudden, an object that we had previously considered to be made of glass or plastic or ceramic, took on much much more meaning. It would recontextualise itself, allowing us to place these materials within a completely different framework. That’s very interesting to us, not only as an institution, but also as people — people who are deeply invested in questions of how materials interact with contemporary life.

"We really try, as much as possible, to avoid categorisation; to avoid the inherent hierarchies which exist in archives and in libraries, and to place trust in the user, allowing them to inform our collections."

The Kunstbibliothek is located in the same space as the Werkstoffarchiv, so that the material samples and literature can be used in parallel and in inspiring dialogue with one another.

KOOZ Two questions. Going back to how we started on the idea of public literacy, when one focuses on the production of knowledge about processes and prototypes, rather than the ‘desirable object’, how does one ensure that the knowledge or literacy involved in experimentation and development is clearly conveyed to the audience? Secondly, I had a question about alliances; you mentioned a network of ten institutions, which enables you to share knowledge. How important are such alliances, to what extent are they necessary for cultural institutions like the Sitterwerk to ensure that they can actually permeate different thresholds, across geographies as well as disciplines?

WS For the Sitterwerk, since the very beginning, it was fundamental that we combine the collections of materials and books in the same room, so we don't see them as being two separate worlds. We understand that there's a synergy between them and that they inform each other. This is something particular to us; it requires special tools to enable the people who spend time with our collections to document their work. We actually focus most of our efforts on developing those tools, not on growing our collection, nor in accumulating new books or the latest materials. It's about developing tools to allow people to access content — not only via their own interests but also tangentially, through the interests of others, as well as tools that will allow users to document their own lines of inquiry, in a very intuitive way.

At the Sitterwerk, it is very easy to look at content physically, using a very analogue, tangible method — a table. The table, known as the "Werkbank", functions as a large format scanner, scanning the content and transmitting this to a digital interface. Here, users can build up a collection of contents, and then (using a template) they can generate a ‘zine or physical brochure — not just a PDF that just gets lost in the ether, but something tangible that they can hold. As naive and simple as that might seem, we find that it's an extremely popular format for people: what resonates is simply this ability to actually organise content in an individually meaningful way, without a great deal of effort and with total freedom. We simply make these things available to them. So for us, the tools are absolutely important.

In terms of our relationships with other institutions, Material Archiv and the other bodies that we work with have been extremely important. We are all small entities, with our own relatively specialised collections. As the Sitterwerk is primarily an art foundry, a lot of our samples are direct experiments from these workshops. We have a lot of plastics, waxes, metal and materials associated with casting processes — but we don't have too much in the way of textile or wood, for example. As institutions, we each have our little focuses, but the expertise, the interest and the knowledge that we generate is shared and made very accessible. I find this to be an extremely potent mode of collaboration, combining internal focus with the benefits of external expertise — that translates to real value for our visitors.

KOOZ Another project which Beatrice mentions in your book is the Róng Design Library, set up by designers to preserve traditional Chinese craft techniques through a collection of objects and materials. As we move towards hyper-digitalisation, such knowledge systems are being forgotten as people pass away, and it's just not there anymore.What is the potential of thinking of broader alliances with potentially similar or analogue realities, outside of specific geographies?

"Connections are, to a certain extent, easily available. What is missing are the means to use these connections as a way to empower realities that can speak to and benefit from one another."

BL Frankly, I am not so sure that we need to constantly think about emphasising and extending things to a “global” multiplicity. We are already connected; digital literacy is unprecedentedly widespread, so I don't think we lack that. Connections are, to a certain extent, easily available. What is missing are the means to use these connections as a way to empower realities that can speak to and benefit from one another. One important subject that we touched on earlier is [the] audience. This is an issue for institutions to understand: exactly who is the audience? Who are they talking to? This idea of a ‘general public' does not exist. There are publics, in the plural, in different ranges. An institution can be many things to many different people, but I think there’s something to be said for acting with precision.

In my book — but also in many of the activities I have overseen as the head of various institutions or projects — what revealed itself as truly important are these moments of methodological sharing among practices. Again, institutions tend to focus on the finished outcome, whatever its shape: the object, the service, the visualisation, the installation, and so on. But when it comes to processes, that is where generally independent practices or practitioners are struggling the most. These moments of confrontation, co-action are very valuable platforms for professionals because they are not really available anywhere else but through the realm of culture. Again, certain perennial events might help with that; biennales, expos and large scale events gather large groups of people. But such opportunities cannot be relegated to the fringes of this kind of festivalism. They are fantastic, we need them — but I think that there is something inherently valuable in connecting practitioners and professionals, which institutions should take up more often as a task.

The best, most courageous and path-bending ideas come from practice. They don't come from academia, they don't come from the corporate sector, the industries; they don't flow top-down. They often come from the bottom up, from grassroots initiatives, from people self organising. This is characteristic, I believe, of the way that the practice of design in general is transforming. The topics, the issues, the literacies with which design is confronted — they demand collaboration, cross-pollination among disciplines and sectors. This idea of the single author, the genius designer, who delivers that perfect object, product or service has been completely debunked. So that's where institutions can play an important role of support.

As with the Saudi Arabian pavilion and the Um Slaim School which I have curated at the current Biennale Architettura in Venice, the whole idea is about using a collective process of knowledge-making to prototype a new pedagogical initiative. Because we do need novel methodologies, novel horizons to think through educational pathways in design and architecture. This is really urgent. With this project, we are taking the opportunity to gather people over six months to collectively address these concerns, of how to adapt design education and pedagogical methodologies to new challenges.

There's plenty to be done, but I really think that providing support to practice is crucial, now more than ever. It’s not like institutions are living through a particularly happy time, considering widespread defunding and the volatility of sponsorship (versus actual long-term investment). Cultural institutions are generally not in great shape right now, neither are our economies or societies, so perhaps this is a good place to start: invest in a new institutional ecology that can benefit all, where culture sits at the centre of that regenerative path.

"This idea of the single author, the genius designer, who delivers that perfect object, product or service has been completely debunked. So that's where institutions can play an important role of support."

KOOZ Wayne, this is something you brought to the Sitterwerk, for instance by embedding the residency programme. You mentioned Material Cultures; there's also the collaboration with Experimental Foundation on light earth, as well as your own background in architectural practice, which carries an interest in circular building practices. How do such residencies and collaborations support practice, and how does that knowledge generated by practice extend beyond the Sitterwerk?

Research work done with the collections on site can be documented and saved for further use using the interactive worktable, the Werkbank.

WS Well, anytime you invite questions from the outside, it refreshes the lifeblood of an institution — I feel this is especially true for an archive. Inherently, archives can be very sedentary; they can become stagnant, fixed and somehow dogmatic in the way that they transmit themselves. By inviting people — especially practitioners, who really encounter so many questions without necessarily finding answers — we allow our content to be deployed in very different ways.

In the case of the Experimental Foundation, researchers Maria Lisogorskaya and Kaye Song came to the Sitterwerk early on in their process, as part of a fellowship programme. The decision to come to a place of art production was not the most obvious one; they come from architecture, after all. What we can offer, however, is a very close proximity to experimental production. For instance, we’re more open to unorthodox ways of using and approaching materials, because the art world is less indebted to public service and some of the restrictions that constrain architectural practice. What they were able to do at Sitterwerk was to examine light earth techniques — as opposed to heavy rammed earth, this is earth in a more experimental, playful, lightweight form — and explore the boundaries and flexibilities of this material.

Through my position, I'm able to put on yet another hat and spend time with them out in the field, experimenting with different tools and techniques, formworks and so on, to help them explore this material in applied experimentation — and in a fun way, and it's important that it stays fun. When researchers come back to the library after a day of experimenting with materials, the collections take on new meanings. Users can see materials in a different context; they can investigate other artists who have done similar works.

We don't really want to overthink it; it really is this ping-pong between practice and research, mutually bouncing off each other.I think the more we have of that, whether it's in the form of two researchers who are looking at a particular material, or creating a module in a semester for an academic programme, we learn as much from these processes of exchange as our collaborators learn from us. That's important to understand: we are not in a role of serving an audience, rather we are informed and expanded by the people who visit us.

"We’re more open to unorthodox ways of using and approaching materials, because the art world is less indebted to public service and some of the restrictions that constrain architectural practice."

KOOZ It’s worth noting the extent to which the experimentation and resource sharing is supported and mediated through Sitterwerk’s excellent digital platforms. How far is the experience of Sitterwerk limited to the potential for physical visits — and where do you draw the line in terms of how much to share online and what to keep ‘in-house’?

WS I think the point is to not draw lines at all — to allow for this vague area of potential. Personally, I don't perceive any clear imperative to decide that one thing should remain analogue while another remains digital. What we’ve come to realise is that users themselves have certain areas of comfort; many are very comfortable browsing through a library in a very physical manner, and they come across new ideas. Other people really need to organise themselves digitally, in a focused and shareable format. C’est la vie; how visitors use the collections is really up to them. I have noticed that there's often an alternating gravitation between the two: people might spend some hours looking at books on tables and handling the materials, then at some point, they need to organise their findings and place them in a format that makes sense to them. We're here to support both.

KOOZ So if I look at the collaboration with Material Cultures on sand, how much of their findings transfer into the digital archive as knowledge — and what remains exclusive to the experience of that exhibition at the Sitterwerk itself? How might the digital platforms work in terms of supporting the exploration and connections that that one might build upon and share.

"Insofar as what makes it into our collection, it’s about the traces that they leave through making connections and links."

WS It's quite a case-by-case treatment, I would say. In the case of Before And After Sand, there was a period of intense research where the team started to dig into the library, into the materials collection, bringing this together on our table, and documenting that as a sort of knowledge bank. This impulse formed the catalyst for many of the ideas that came later, which were much more technical and which relied less directly on our collections. The research in that case developed to become specifically attuned to the UK, by the members of the Material Cultures team. Insofar as what makes it into our collection, it’s about the traces that they leave through making connections and links. If they pulled out books on artists who used sand or developed certain processes, these are traces, lines that can be picked up by other users, either via the catalogue or through intuitive association. It’s not that their input has left something static; it remains open to potential.

Panel discussion accompanying the exhibition “Before and After Sand” in collaboration with Material Cultures

KOOZ Looking ahead, what have you learned from these programmes, and how has that process shaped your activities for 2026 and beyond?

WS In some ways, it’s about growth in two directions. Firstly, it’s about growing inward; we want to intensify the work that we're doing here, even developing a more localised hub for practitioners and researchers to meet each other. We too feel that this constantly expansive network, growing outwards, does not necessarily bring us closer together. I find that Sitterwerk’s users appreciate working within the constraints of this place, its system of analogue searching and its limited collection. Our material stays here, it doesn't wander outwards. This condition generates a lot of variety within — so that rather than searching the internet, they search this internal network in alternative ways. On the other hand, we do try to cultivate relationships with other institutions, in order to make people aware that there are other ways of organising content. That’s not to say that we are a great model for everything — not at all. We're always looking for people who can inform, guide and advise us as well. But we do try hard to make meaningful connections with with external institutions and practitioners, so that whether they're coming to visit us or we're participating in platforms like this, the Sitterwerk doesn't become an insulated box or, a cosmos in itself; that is absolutely not what we wish to be.

KOOZ What about reaching younger generations? Many people embark on architectural or design education without knowing what it’s about. But actually would have been maybe interesting for school-age audiences to confront and develop an awareness of material ecologies, properties and narratives — is that on the agenda?

WS Yes, often; we regularly run cooperations with academic institutions. While these tend to be at the university level, we do have programmes for younger visitors as well, as well as a lot of community events. We hold practical workshops about different types of production techniques; this Saturday we have an Open Museums night, with a panel discussion about authorship in art. We're going to open up the foundry for people to experience a casting. What we try to do is reach a large audience at different levels. Sometimes that's academic, and sometimes it's really our local community.

KOOZ Beatrice, any last thoughts before we close for today?

BL The topics we’ve discussed are really multifaceted. The issue, as always, is what one decides to act upon. Something I always say, when I speak with students about institutional practice, is that the activities of an institution are a form of intervention in discourse through practice. This requires precision and a certain kind of persistence, which is difficult to maintain if you're sitting in the wrong board room. I think bringing these issues to the fore is really important. It requires the constant intention of exchange and debate, so thank you for the opportunity.

KOOZ Thank you both so much for your time and generosity.

About

OBEL is a foundation that recognises and rewards architecture’s potential to act as tangible agents of change that contribute positively to social and ecological development globally. Founded in 2019, OBEL values the plurality of architecture as a practice through expanding who and what defines our built environment. Through various activities, OBEL supports influential ideas and approaches that can spearhead and seed future developments, while driving architectural discourse and education.

The Sitterwerk Foundation holds the aim, as a non-profit, to operate and further develop a public centre for art and production on the grounds of the former Textilfärberei Sitterthal (textile dying plant) in St.Gallen. The Sitterwerk Foundation includes the Art Library, the Material Archive, and the Studio House for guest artists. Felix Lehner, Hans Jörg Schmid, and Daniel Rohner established the foundation in 2006. At irregular intervals, the foundation organises exhibitions, workshops and conferences on the topics of books, material culture and alternative knowledge organisation.

The Sitterwerk Foundation’s Werkstoffarchiv is a collection of material samples organized as a physical and digital reference work. The collection of materials from art production, restoration, architecture, and design was developed in cooperation with the neighboring Kunstgiesserei and the Material-Archiv network, and is constantly being expanded and made accessible. The holdings can be viewed via the Sitterwerk Catalogue, and detailed background information on the individual material samples can be found on the Material-Archiv knowledge portal. The Werkstoffarchiv is located in the same space as the Kunstbibliothek, which means that the collections can be used in parallel and linked by means of compilations on the Werkbank, an interactive table.

Bios

Beatrice Leanza is a cultural strategist, museum director, and critic with expertise in design and arts across Asia and beyond. Leanza has served as executive director of MAAT (Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology) in Lisbon, director of mudac (Museum of Design and Applied Arts) in Lausanne, and creative director of Beijing Design Week, where she launched the Baitasi Remade urban regeneration program. She also co-founded The Global School, China’s first independent institute for design and creative practice. Her book The New Design Museum (Park Books, 2025) explores emerging institutional practices in design and architecture addressing twenty-first-century challenges.

Wayne Switzer is an architect and educator working at the intersection of materials and building culture. Since 2024, he oversees the Material Archive at the Sitterwerk Foundation, where he guides practitioners and curates exhibitions. His most recent exhibition — Before and After Sand (2024) — examined the formation and future of sand beyond its contemporary exploitation. His teaching and research focuses on circular building practices and the development of bio-based materials within contemporary construction.

Federica Sofia Zambeletti is the founder and managing director of KoozArch. She is an architect, researcher and digital curator whose interests lie at the intersection between art, architecture and regenerative practices. In 2015 Federica founded KoozArch with the ambition of creating a space where to research, explore and discuss architecture beyond the limits of its built form. Parallel to her work at KoozArch, Federica is Architect at the architecture studio UNA and researcher at the non-profit agency for change UNLESS where she is project manager of the research "Antarctic Resolution". Federica is an Architectural Association School of Architecture in London alumni.