Edited by Hugo Palmarola, Eden Medina and Pedro Ignacio Alonso, How To Design A Revolution: The Chilean Road to Design (Lars Müller Publishers, 2024) gathers and expands on research documenting a surreal period in Latin American history. The German designer, educator and theorist Gui Bonsiepe — who advised on Chile’s Project Cybersyn — compared it to ‘a science fiction story.’ In this extract, Eden Medina delves into the strange history of Cybersyn, entangling nationalist politics, computational analysis and space-age design.

How to Design a Revolution: The Chilean Road to Design, edited by Hugo Palmarola, Eden Medina, and Pedro Ignacio Alonso (Lars Müller Publishers, 2024), book cover.

When Allende came to power, he and his government knew that the success of his socialist program would hinge on the success of his economic program. This included nationalising Chile’s most important industries and raising industrial production levels. By the end of Allende’s first year in office, it had become clear that both goals presented substantial challenges. Addressing these challenges opened the door to new possibilities in economic management.

The president viewed the nationalisation of Chilean-owned and foreign owned enterprises as a key accomplishment of his government’s first year. On November 4, 1971 (the first anniversary of his presidency), Allende addressed the Chilean public from the National Stadium in Santiago and said of nationalisation, “Chileans have recovered what belongs to them, their basic wealth, which was formerly held by foreign capital. We have defeated monopolies and the oligarchy. Both of these advances are essential to break the chains which bind us to underdevelopment.”1 By the end of 1971, the state was responsible for running twelve of the twenty largest companies in the country and had nationalised more than 150 enterprises overall.2 [...]

The government placed its nationalisation effort under the control of the Corporación de Fomento de la Producción (State Development Corporation, CORFO), an agency that had been created in 1939 to help the country recover from the Great Depression. It had no experience managing the most important industries in the economy. However, the general technical manager of CORFO, a young engineer named Fernando Flores, had an idea. He remembered reading a work in the field of management cybernetics written by a British cybernetician named Stafford Beer. The term “cybernetics” emerged after World War II to refer to the interdisciplinary science of feedback and control that drew from fields such as mathematics, engineering and neuropsychology to study the behaviour of biological, mechanical and social systems and how to regulate them. Beer, a British management consultant, applied these concepts to the management of firms and had done so quite successfully.

This collaboration gave rise to a new experimental system for economic management that built new communication channels, tools for data collection, visualisation and analysis, as well as environments for decision-making.

His work sought to transform industries into self-regulating systems that could respond quickly to dynamic changes in their environment. Flores saw management cybernetics as a way for Chile to increase its control of the growing Social and Mixed Property Areas, while also raising levels of production nationally. He invited Beer to come to Chile to help the government improve its economic management capabilities. Beer accepted the invitation and arrived in Santiago on the celebration day of Allende’s first year in office. This collaboration gave rise to a new experimental system for economic management that built new communication channels, tools for data collection, visualisation and analysis, as well as environments for decision-making. In less than two years, a multidisciplinary project team bridging Chile and England established a network of telex machines that spanned Chile’s long, narrow geography and connected the upper reaches of the government to the newly nationalised factories.

The room they eventually built looked like something out of a science-fiction film. Four components — the telex network, statistical software, economic simulator and operations room — collectively formed the Cybersyn project.

The team developed a new suite of custom software that applied statistical methods to data collected from nationalised factories to predict production trends and raise alarms about potential economic problems. The team also started working on an economic simulator that would allow policymakers to test the effects of different policy decisions. This prototype simulator was designed to give those in government a means to play with different economic policies and, through play, better understand how different parts of the economy fit together and shape one another. Finally, team members created a prototype operations room that they hoped to re-create in different spaces throughout the country. The room they eventually built looked like something out of a science-fiction film. Four components — the telex network, statistical software, economic simulator and operations room — collectively formed the Cybersyn project. As a portmanteau of cybernetics and synergy, the project name recognized both the interdisciplinary science that provided its conceptual core and that the system as a whole was more than the sum of its component parts.

Cybersyn in the History of Design

Each of these four subprojects could easily be viewed as examples of design, if we view design as a form of intelligent problem solving.3 For example, in the case of the telex network, members of the Chilean team decided where to place each telex machine to create the new communications channels that the government would need to respond to a crisis. This included setting up a central telex-linked command hub in the presidential palace, as well as a series of specialised command centres in areas such as transportation, industry and energy, during a nationwide opposition-led lockout that threatened to bring the Allende government to an early end. These command centres also used telex machines to connect the people working in these different areas to the presidential palace and the shop floor. [...]

However, the Cybersyn operations room is the only subproject of the four that involved industrial and graphic design professionals, including designer Gui Bonsiepe, who had studied and taught at the famed design school Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm (HfG Ulm) in Germany. In addition, the room is the only subproject with ties to the institutional history of Chilean industrial design. It thus constitutes the focus of the rest of this essay.

How to Design a Revolution: The Chilean Road to Design, edited by Hugo Palmarola, Eden Medina, and Pedro Ignacio Alonso (Lars Müller Publishers, 2024).

Project Cybersyn grew out of the Flores-Beer connection. However, the connection between Flores and Bonsiepe also proved central to the design of the Cybersyn operations room. In addition to his role as general technical director of CORFO, Flores served as the president of the Comité de Investigaciones Tecnológicas de Chile (State Technology Institute, INTEC), a government research and development centre charged with improving Chilean industrial capabilities. While at INTEC, he used his power to create the Área de Diseño Industrial (Industrial Design Area), Chile’s first state industrial design group, which he placed under the leadership of Bonsiepe, whom he had met through a mutual friend.

Bonsiepe arrived in Chile in 1968, after the HfG Ulm closed. Once in Santiago, he began mentoring a group of four students from the University of Chile: Guillermo Capdevila, Rodrigo Walker, Fernando Shultz and Alfonso Gómez. These students followed Bonsiepe when he accepted a teaching position at the Catholic University School of Engineering. When Bonsiepe accepted the position at INTEC, they followed him again and joined the new Industrial Design Area. Bonsiepe expanded the group further by recruiting several recent graduates from the Ulm School. Collectively, this group would develop nearly twenty products for the Allende government, including the design for the Cybersyn operations room. Outside INTEC, Bonsiepe worked with a team of graphic designers who created visual elements for a range of projects, including the graphics projected on the operation room’s central data displays.

The room bears the hallmarks of Bonsiepe’s work and the approach to design he helped develop at HfG Ulm. This includes bringing insights and methods from science to the practice of design, embracing the development of local solutions to industrial problems, viewing design as a political act.

The room bears the hallmarks of Bonsiepe’s work and the approach to design he helped develop at HfG Ulm. This includes bringing insights and methods from science to the practice of design, embracing the development of local solutions to industrial problems, viewing design as a political act and recognising how design can allow people to imagine and build the world they want to inhabit.4 The room’s explicit connection to the advancement of Chilean democratic socialism and goals — such as the improvement of living standards for poor and working-class Chileans and Chile’s forging of its own political path — also aligned with Ulm School commitments to democracy, self-determination, autonomy and the improvement of the economic and social status of the marginalised. Intellectually, the design of the room drew from fields such as cybernetics, semiotics and system theory, just as the Ulm School had.5 As Bonsiepe later observed: “There are not many examples of the convergence between social responsibility, advanced technology and design.” However, the Chilean cybernetic management centre “can be considered an exception.”6

How to Design a Revolution: The Chilean Road to Design, edited by Hugo Palmarola, Eden Medina, and Pedro Ignacio Alonso (Lars Müller Publishers, 2024).

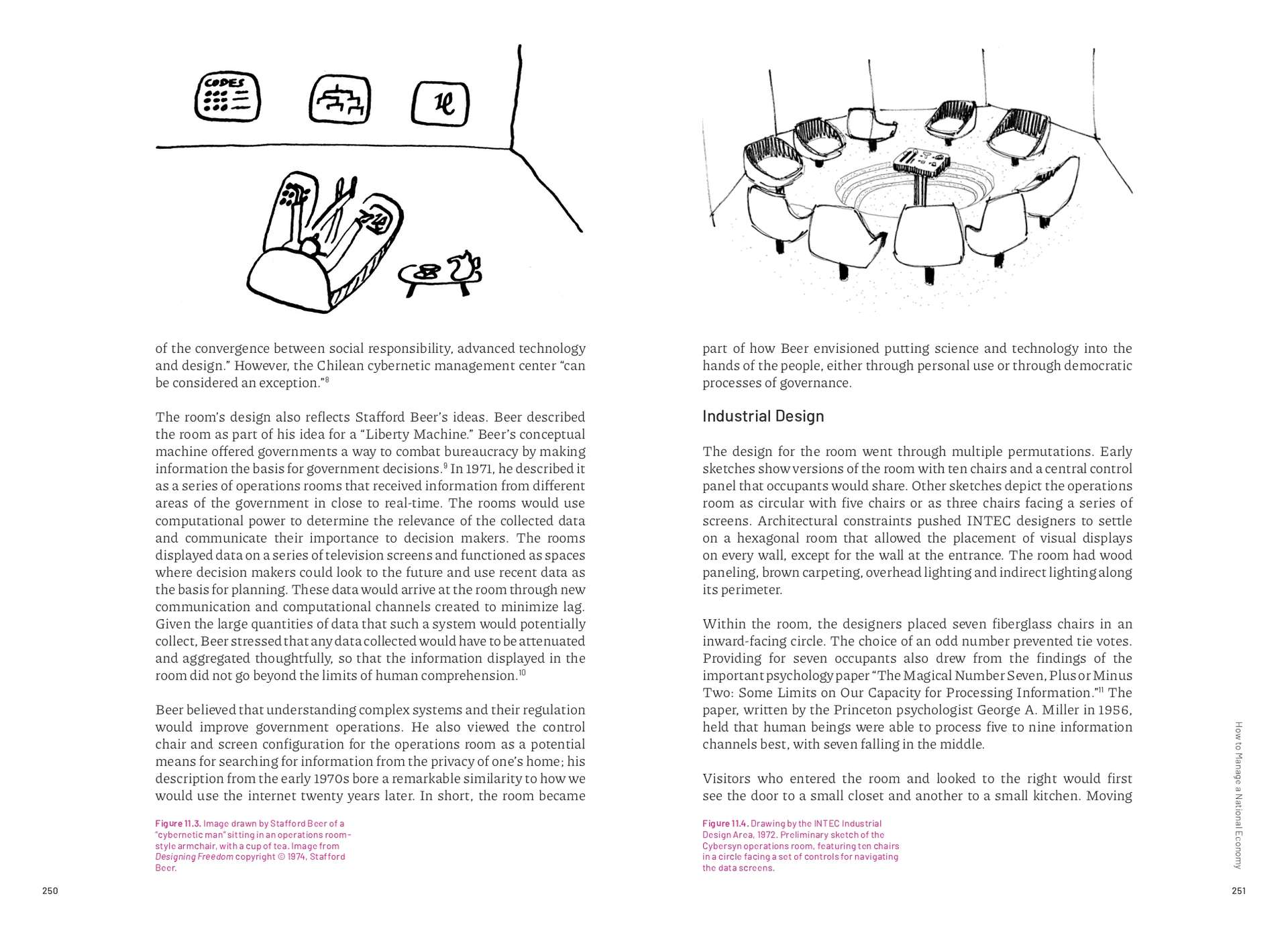

The room’s design also reflects Stafford Beer’s ideas. Beer described the room as part of his idea for a “Liberty Machine.” Beer’s conceptual machine offered governments a way to combat bureaucracy by making information the basis for government decisions.7 In 1971, he described it as a series of operations rooms that received information from different areas of the government in close to real-time. The rooms would use computational power to determine the relevance of the collected data and communicate their importance to decision makers. The rooms displayed data on a series of television screens and functioned as spaces where decision makers could look to the future and use recent data as the basis for planning. These data would arrive at the room through new communication and computational channels created to minimise lag.

Given the large quantities of data that such a system would potentially collect, Beer stressed that any data collected would have to be attenuated and aggregated thoughtfully, so that the information displayed in the room did not go beyond the limits of human comprehension.8 Beer believed that understanding complex systems and their regulation would improve government operations. He also viewed the control chair and screen configuration for the operations room as a potential means for searching for information from the privacy of one’s home; his description from the early 1970s bore a remarkable similarity to how we would use the internet twenty years later. In short, the room became part of how Beer envisioned putting science and technology into the hands of the people, either through personal use or through democratic processes of governance.

Industrial Design

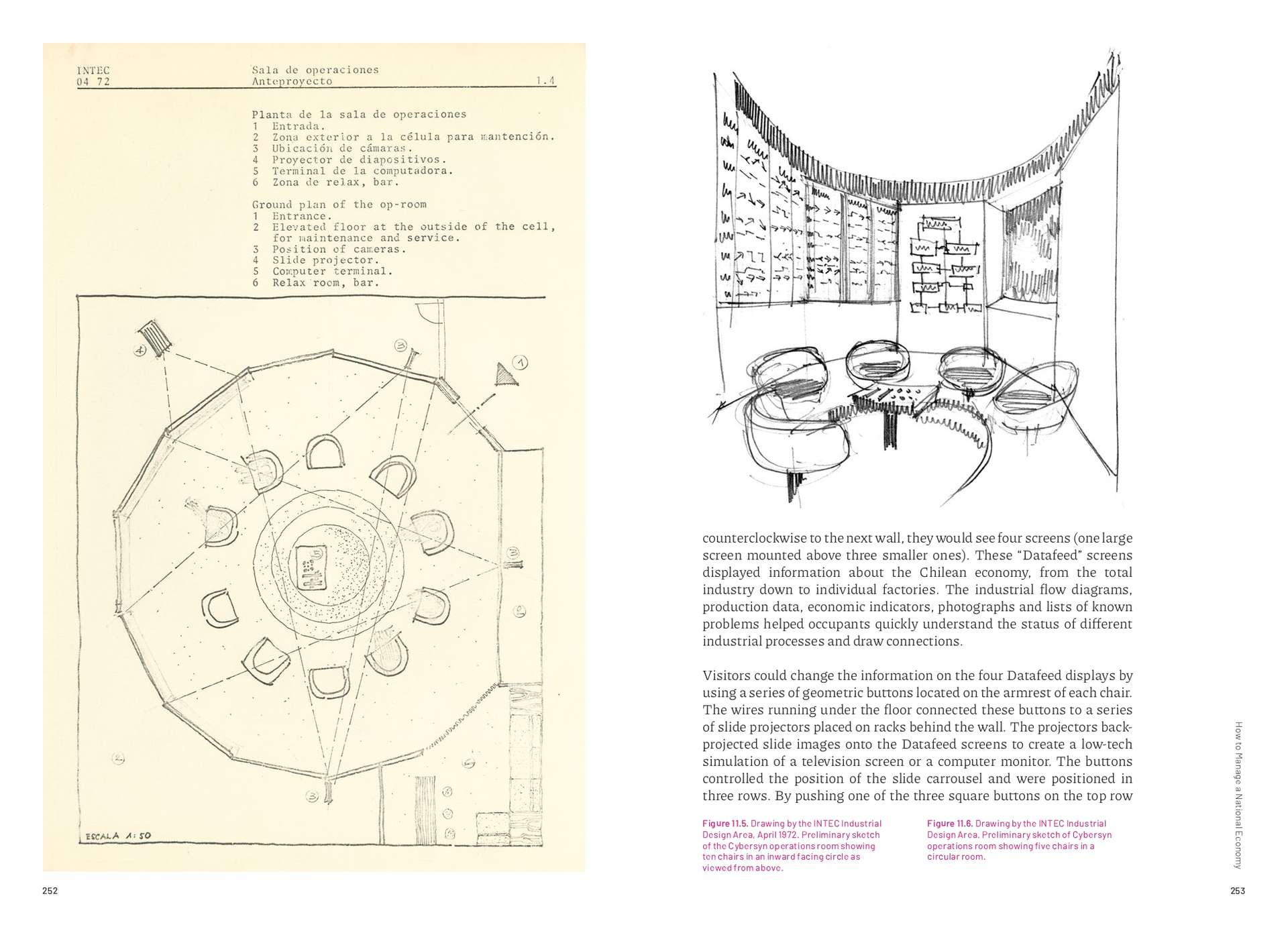

The design for the room went through multiple permutations. Early sketches show versions of the room with ten chairs and a central control panel that occupants would share. Other sketches depict the operations room as circular with five chairs or as three chairs facing a series of screens. Architectural constraints pushed INTEC designers to settle on a hexagonal room that allowed the placement of visual displays on every wall, except for the wall at the entrance. The room had wood panelling, brown carpeting, overhead lighting and indirect lighting along its perimeter.

How to Design a Revolution: The Chilean Road to Design, edited by Hugo Palmarola, Eden Medina, and Pedro Ignacio Alonso (Lars Müller Publishers, 2024).

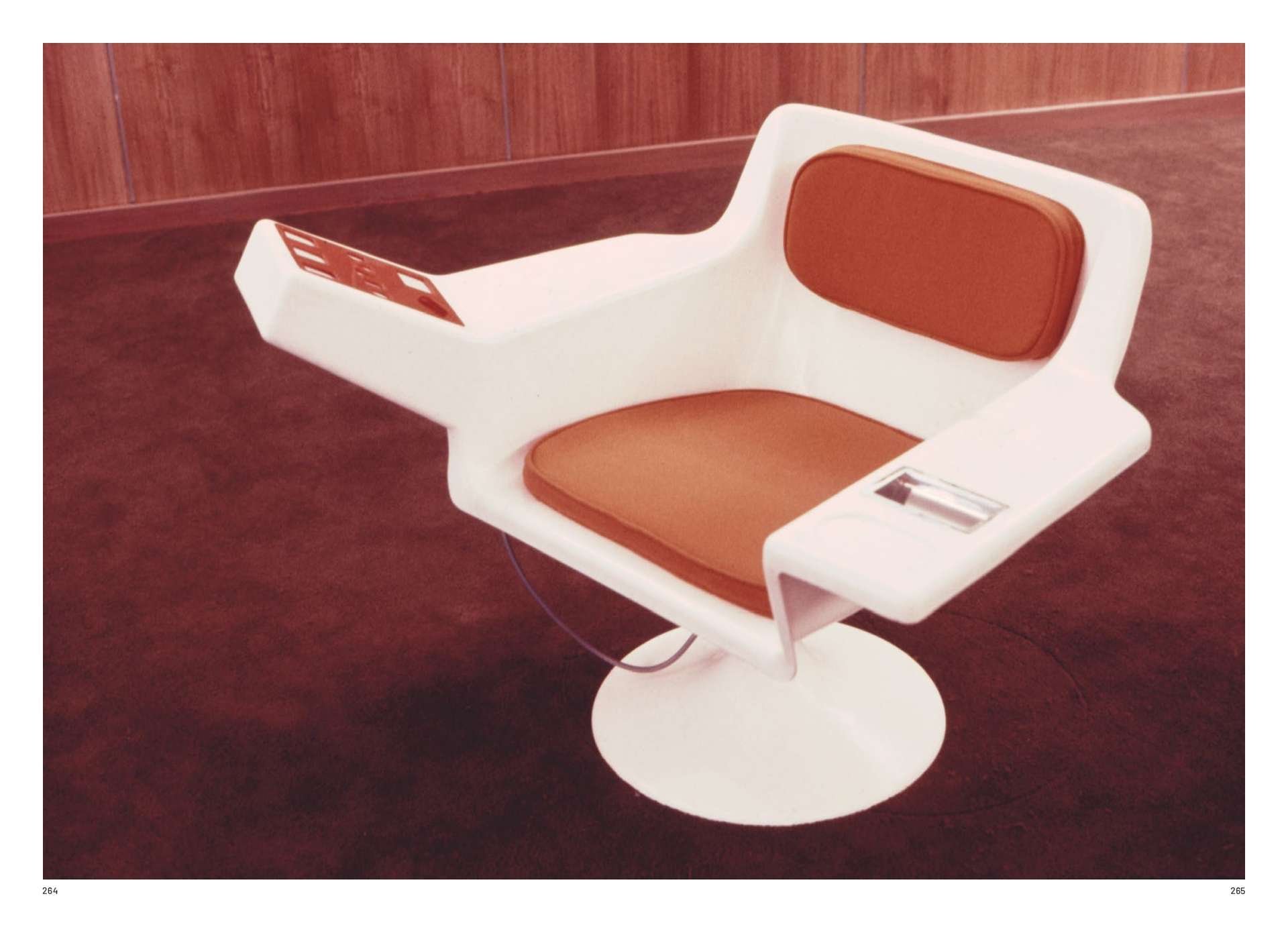

Within the room, the designers placed seven fibreglass chairs in an inward-facing circle. The choice of an odd number prevented tie votes. Providing for seven occupants also drew from the findings of the important psychology paper The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information.9 The paper, written by the Princeton psychologist George A. Miller in 1956, held that human beings were able to process five to nine information channels best, with seven falling in the middle. Visitors who entered the room and looked to the right would first see the door to a small closet and another to a small kitchen. Moving counterclockwise to the next wall, they would see four screens (one large screen mounted above three smaller ones). These “Datafeed” screens displayed information about the Chilean economy, from the total industry down to individual factories. The industrial flow diagrams, production data, economic indicators, photographs and lists of known problems helped occupants quickly understand the status of different industrial processes and draw connections.

Visitors could change the information on the four Datafeed displays by using a series of geometric buttons located on the armrest of each chair. The wires running under the floor connected these buttons to a series of slide projectors placed on racks behind the wall. The projectors backprojected slide images onto the Datafeed screens to create a low-tech simulation of a television screen or a computer monitor. The buttons controlled the position of the slide carrousel and were positioned in three rows. By pushing one of the three square buttons on the top row the options menu shown on the large top screen, or “control screen,” changed. This screen told users which combination of geometric buttons to push on the second row to navigate the menu screen and bring up the information they wished to see; this data would appear on one of the smaller “data screens.” A diamond-shaped button containing a red light on the bottom row signalled that the system was in use and blocked other users from changing the slides. A reset button, also located on the bottom row, restarted the process. A person located behind the wall maintained the slide projectors and had their own set of button controls. The maintenance person used an intercom to communicate with the people in the room.

How to Design a Revolution: The Chilean Road to Design, edited by Hugo Palmarola, Eden Medina, and Pedro Ignacio Alonso (Lars Müller Publishers, 2024).

Creating an interface based on ten geometric buttons, rather than a traditional keyboard, made the room accessible to those without typing skills, such as workers (or members of the government elite who had secretaries). However, this design decision also replicated the Cold War desire to control the outside world by pushing a button. As media scholar Rachel Plotnick writes in her book Power Button, push buttons seem to offer an “effortless technical experience” and a form of command whereby a small movement of the hand can “direct anyone or anything to submit to their will.”10 As a design decision, these buttons visually furthered the mystique of the room as a space for control. However, the interface was difficult to navigate in practice. Moreover, the final design lacked a key feature of the button-pushing experience, namely, feeling its downward motion. While the buttons were originally designed to have a height of 32 mm and travel downward a distance of 20 mm when pushed, the team encountered difficulties in acquiring the necessary component parts. In the final design, the buttons were nearly flush with the armrest panel and only travelled 3 mm. Moving counter clockwise again, the visitor would next see a wall with two panels that displayed economic emergencies, or what Beer referred to as “algedonic signals.” These alerts quickly conveyed the areas of industrial production that needed immediate attention. If left unattended, these emergencies could affect the overall stability of the Chilean economy and, by extension, threaten the stability of the government.

The algedonic panels connected the room to the daily economic data that the Cybersyn system collected from the state-run factories by telex and were entered in the statistical software for analysis. This software generated an alert whenever a production index fell outside an acceptable range of values. The members of the Cybersyn team initially communicated these alerts to the appropriate enterprise manager. However, they would communicate the alert to higher levels of management if the enterprise manager could not solve the problem within a given period. The alert would work its way up the management hierarchy. It would eventually appear in the room printed on a piece of acrylic tape that the maintenance person would place on one of the two algedonic panels. This would make the alert visible to the room’s occupants and shape their discussion. The panels used light and colour to help occupants contextualise the problems and prioritise their decision-making. The designers divided the two panels into blocks of different colours. The left panel had a sky blue background and was used to communicate exceptional situations in urgent need of a solution. The right panel had three coloured blocks — one green, one yellow and one red. Each block denoted the level the alert had reached within the management hierarchy. Emergencies at the enterprise level appeared on the acrylic tape placed over the bottom section, which had a green background. Those at the sector level appeared in the yellow middle section. Those at the branch level appeared at the top, which had a red background. Each acrylic label contained the name of the enterprise that had generated the alert, the abnormal production index and an arrow that communicated whether the index was rising or falling. The person located behind the wall could change the acrylic tape by using an opening at the back of each panel. The square red lights positioned beside each of the coloured blocks used different intensities to indicate the seriousness of the alert.

How to Design a Revolution: The Chilean Road to Design, edited by Hugo Palmarola, Eden Medina, and Pedro Ignacio Alonso (Lars Müller Publishers, 2024).

Moving counter clockwise once again, visitors would see another wall with a framed image of the “Viable System Model,” the cybernetic model developed by Stafford Beer that served as the conceptual foundation for Project Cybersyn. The design team referred to the framed model affectionately as “Staffy,” in reference to Beer. The cybernetician wanted the room to have a representation of the Viable System Model to help occupants visualise the principles of cybernetic management. However, the complexity of the model made it difficult to understand, leading some to question the value of the Staffy display.11 Beer’s son, Simon, constructed the display and sent it to Chile for use inside the room.12 Two screens placed next to “Staffy” allowed for the projection of additional data. Moving counter clockwise a final time would lead visitors to a wall with a metallic screen covered in fabric. Occupants used the screen to position magnets of different shapes, each representing a different part of the Chilean economy. By allowing those in the room to explore different economic relationships, the magnetic board functioned as a low-tech version of the Cybersyn economic simulator.

Beer continued to provide feedback to the design team as the work progressed. For example, in March 1972, he made it clear that the “Operations Room should be thought NOT as a room containing interesting bits of equipment BUT as a control machine comprising men and artefacts in symbiotic relationship.”13 However, he did not provide the team with a clear list of requirements, as was typical for the design process. “There is no reference point,” said the INTEC industrial designer Rodrigo Walker in an interview. “[If] I tell you, ‘Let’s go build a movie theatre,’ you have a reference point [. . .] you can begin to imagine what it would look like. But there was no operations room [here], there was nothing that one could look at.”14

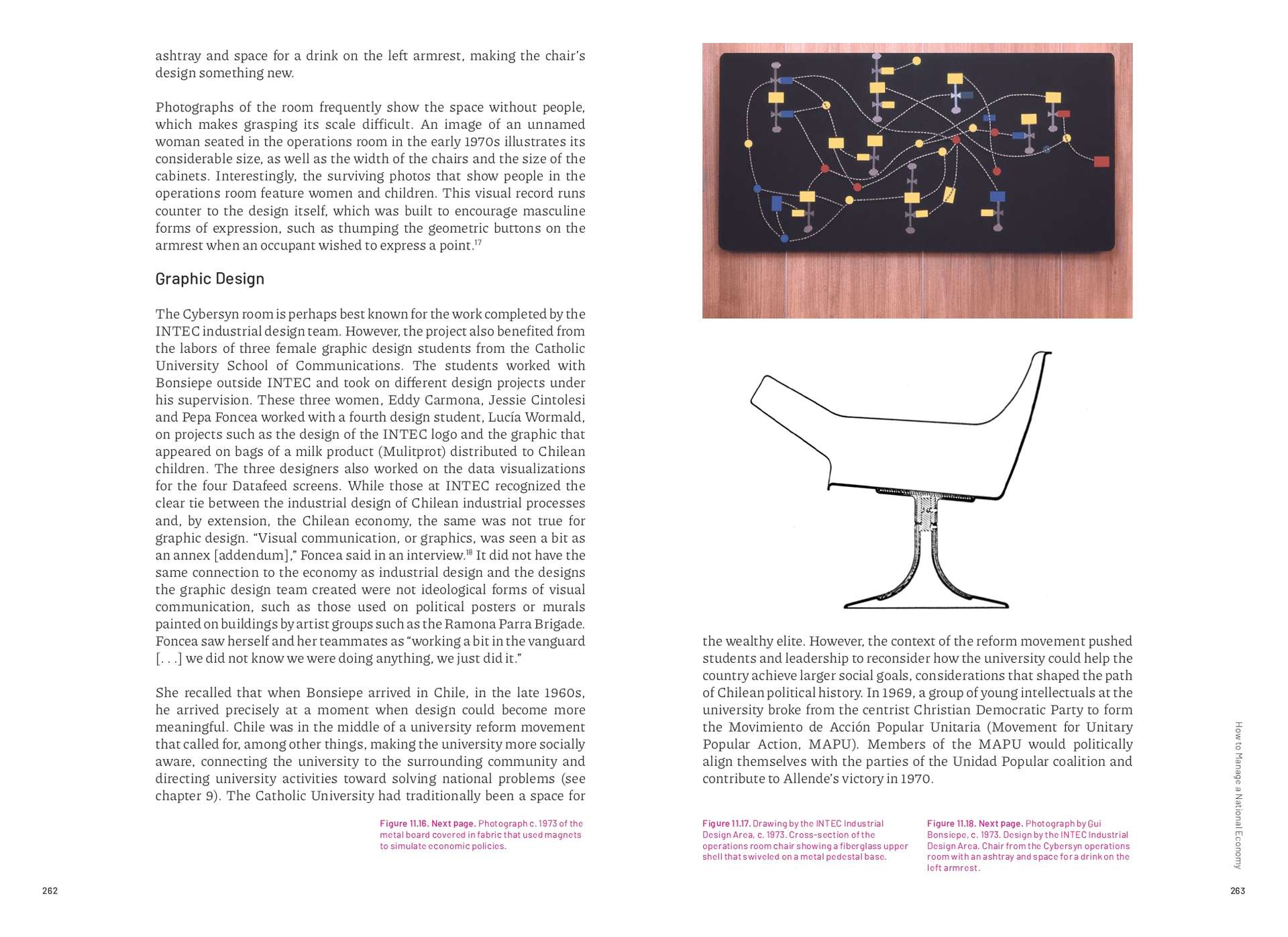

The eventual design of the room resembled something out of a science fiction movie such as Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey — although the designers denied the direct influence of science fiction on their work. Instead, they recalled looking at Italian designers and their use of materials such as fibreglass reinforced with polyester. This material permitted Chilean designers to construct chairs and cabinets for the room that had smooth curved lines. The operations room chairs also bore a resemblance to the modernist Tulip chair created by Finnish-American designer Eero Saarinen. Like the Tulip chair, the operations room chairs had an upper shell made of fibreglass and swivelled on a metal pedestal base. Unlike the Tulip chair, the operations room chair included an electronic button interface on the right armrest and an ashtray and space for a drink on the left armrest, making the chair’s design something new.

Photographs of the room frequently show the space without people, which makes grasping its scale difficult. An image of an unnamed woman seated in the operations room in the early 1970s illustrates its considerable size, as well as the width of the chairs and the size of the cabinets. Interestingly, the surviving photos that show people in the operations room feature women and children. This visual record runs counter to the design itself, which was built to encourage masculine forms of expression, such as thumping the geometric buttons on the armrest when an occupant wished to express a point.15 [...]

A Rupture in Design History

Construction of the room began in 1972. It was unveiled as a working prototype at the end of the year, during the peak of the Chilean summer. Allende visited the room on the last day of December, sat in one of the chairs and pushed the buttons. However, the heat of the summer day had pushed the electronics outside their tolerance. “The projectors went crazy,” Walker recalled in a 2006 interview. “You would push [the armrest button] for one thing and something else would appear.”16 Roberto Cañete, the project translator, offered a similar account in his telexed message to Beer following the president’s visit. The room’s electronics “behaved awfully,” he wrote.17 Despite this limited functionality, the room captured the president’s imagination. According to a published account, he told the team, “Shoot, it would be good to have it working. Keep going.”18

Allende communicated that he wanted Bonsiepe to move the room to the presidential palace in early September 1973. That never happened — the military coup took place shortly after. Work on the project stopped abruptly once the military assumed power. The military coup, and the violence that followed, created a rupture in Chilean design history, stopping projects, disbanding teams and making it impossible for design to have the same political significance it once had.

Bonsiepe fled Chile by crossing the Andean cordillera with documents from the project smuggled in the back of his car. Graphic designer Pepa Foncea, who helped to create the information visualisations for the data feed, recalled burning selected books and documents about information design that she believed could bring harm to her or her teammates, because of the violent acts the military dictatorship was committing to eliminate communism. “We burned it,” she said, but “it’s not that we forgot it.”19

This essay is adapted from one of the twelve articles that appear in the book How to Design a Revolution: The Chilean Road to Design, edited by Hugo Palmarola, Eden Medina, and Pedro Ignacio Alonso (Lars Müller Publishers, 2024). It appears here courtesy of the publisher and editors. The book ties to an exhibition of the same name that appeared at the La Moneda Cultural Center in Santiago, Chile from September 7, 2003 to January 28, 2024. As part of the exhibition, Palmarola, Medina, and Alonso created the first functional and comprehensive reconstruction of the Cybersyn operations room. The Industrial Design Area of the State Technology Institute (INTEC) created the original design in 1972 to 1973.

Bio

Eden Medina is associate professor in the Program for Science, Technology and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and a historian of science and technology. She is the author of Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile (MIT Press, 2011), which won the 2012 Edelstein Prize for best book on the history of technology and the 2012 Computer History Museum Prize for best book on the history of computing. Her coedited volume, Beyond Imported Magic: Essays on Science, Technology, and Society in Latin America (MIT Press, 2014), received the Amsterdamska Award from the European Society for the Study of Science and Technology (2016). Her research studies the relationship of science, technology, design and processes of political change. She holds a Ph.D. in the history and social study of science and technology from MIT and a master’s in studies of law from Yale Law School.

Notes

1Salvador Allende, “First Anniversary of the Popular Unity Government,” in Salvador Allende Reader: Chile’s Voice of Democracy, ed. James D. Cockcroft (Hoboken: Ocean Press, 2000), 117.

2Barbara Stallings, Class Conflict and Economic Development in Chile, 1958–1973 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1978), 131.

3As Gui Bonsiepe notes in his 2005 lecture “Democracy and Design,” which he delivered in Santiago, Chile, the term “design” is often associated with packaging or styling instead of, in the words of the famed designer James Dyson, “intelligent problem solving.” Building on this latter definition, Bonsiepe observes that “it is no longer feasible to limit the notion of design to design disciplines such as architecture, industrial design, or communication design because scientists are also designing/projecting.” Bonsiepe led the design of the Cybersyn operations room. His lecture was subsequently published as “Design and Democracy,” Design Issues 22, no. 2 (2006): 27–34.

4For an introduction to Bonsiepe’s writings, see Frederico Duarte, “Nostalgia Is Futile-Our Future Starts Now,” in The Disobedience of Design: Gui Bonsiepe, ed. Lara Penin (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), 3–10.

5See Gui Bonsiepe, “The Relevance of the Ulm School of Design Today,” in The Disobedience of Design: Gui Bonsiepe, ed. Lara Penin (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), 26–32; Gui Bonsiepe, “The Invisible Facets of the HfG Ulm,” Design Issues 11, no. 2 (1995): 11–20.

6Gui Bonsiepe, “Opsroom: Interface of a Cybernetic Management Room,” in The Disobedience of Design: Gui Bonsiepe, ed. Lara Penin (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), 381.

7Stafford Beer, “The Liberty Machine: Can Cybernetics Help Rescue the Environment?,” Futures 3, no. 4 (1971): 338–48.

8Stafford Beer, Designing Freedom (Toronto: House of Anansi, 1993), 69.

9George A. Miller, “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information,” Psychological Review 63, no. 2 (1956): 81–97.

10Rachel Plotnick, Power Button: A History of Pleasure, Panic, and the Politics of Pushing (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018), xvi, 227.

11Bonsiepe, “Opsroom,” 387.

12Raúl Espejo, personal communication with the author, March 27, 2023.

13Stafford Beer, “Project Cybersyn,” March 1972, box 60, Stafford Beer Collection, Liverpool John Moores University.

14Rodrigo Walker, interview by the author, Santiago, Chile, July 24, 2006.

15For more on the gendered aspects of the room’s design, see Eden Medina, Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 125–28.

16Walker, interview by the author.

17Roberto Cañete, telex to Stafford Beer, January 3, 1973, box 66, Stafford Beer Collection, Liverpool John Moores University.

18Juan Andrés Guzmán, “Fernando Flores habla sobre el proyecto Synco,” The Clinic, July 24, 2003, 9.

19Carmen (Pepa) Foncea, interview by the author, Santiago, Chile, July 25, 2006.