Abstract

Eterotopia’s territorial research laboratory dived into the depths of the landlocked seas of the archipelago of La Maddalena to find the basis for a design practice on a territorial scale. Nine days of research on this territory laid the groundwork for a new dialogue between its inhabitants, the administration and the layers that thicken places as rich as La Maddalena Archipelago. The latter is a complex model of interdependent and connected relationships which, in its uniqueness, is representative of different types of isolated systems found elsewhere. Throughout its history this island within an island has experienced a continuous flow of occupation and abandonment, from the Napoleonic army to the prolific presence of NATO and from the failed affair of the G8 complex to the seasonal anthropic load of mass tourism. The collected texts from this research explore the layering, the histories, the imagery and architecture that celebrate the unexpected alliances between the land and its occupants through the lens of a collective and transdisciplinary work on the field.

Telling the (hi)story of a territory: how to express its heterogeneous stratifications, the faces and facets of its ambivalent situations, its morphology and its intangible experiences using the same lexicon within a common framework of investigation or dialogue?

After years of research on the Italian territory we still wonder about the meaning of the territorial principle, as well as the need to be able to grasp this complexity and embrace it in our everyday practices and activities. These should move away from the centralizing dynamics of representative and administrative tools, from the concept of perimeter and from the separatist and elite thresholds of knowledge.

“The island as a metaphor, or also as a space that can be used to describe a boundary, or a framed piece of nature. It is useful to describe the world as many scientists and naturalists have done” - Luis Callejas

La Maddalena Archipelago is a perfect case study for analysing contemporary territorial issues, which are crucial to this specific area but are reflected in so many other places. Looking cautiously at the archipelago we soon perceived the paradoxical side of wanting to summarize the identity of this territory. The research led us to pith the following research topics, which will be discussed later in the essay:

Outposts - Architecture that defends the territory;

Tabula rasa - Designing in an uncontaminated territory;

The base of the Statue of Liberty - La Maddalena and the rest of the world;

Insularity - Isolation and reconnection;

The failed conquest - The stratification of failure;

The human load - A community of aliens;

Another nature - The wind, the stars, the Mediterranean maquis;

Archipelago - a sea full of lands, a land full of sea.

These themes manage to range across several issues that are specific to the area of La Maddalena. They are also excellent insights into contemporary times and how these dynamics are being recreated elsewhere. Military occupations, mass tourism and the pristine richness of the landscape, the sea as a space of connection and extractivism are some of the themes we focused on that led us towards the idea that such an isolated territory is actually a case study model for numerous contemporary phenomena.

“The island as a metaphor, or also as a space that can be used to describe a boundary, or a framed piece of nature. It is useful to describe the world as many scientists and naturalists have done” said Luis Callejas, island expert and landscape architect, during his lecture at our laboratory in La Maddalena. The approach taken sought to flesh out the intangible, the value of legends, stratifications and interspecies collaborations that occur in the archipelago. We, thus, asked ourselves: how is it best to conduct field research on a paradigm territory? What does it mean to design a practice that uses heterotopia as a lens to interpret the world around us and its possible transformations?

What does it mean to design a practice that uses heterotopia as a lens to interpret the world around us and its possible transformations?

Eterotopia first emerged in 2018 in the guise of an event in the La Maddalena Archipelago. As multifaceted as the place that welcomed its debut, Eterotopia gave its name to the territorial laboratory and the group of people who created it. The latter brought together more than 120 researchers and planners, architects and sociologists, photographers and biologists, archaeologists and artists, sound designers and urban planners. The result is eight design visions and numerous reflections on the governance of the territory and its transformations. Springing from the enthusiasm which produces such utopias, this project brought together the very different interests of ten young Italian architects who shared a common interest in the study of this complex and stratified territory in which inhabitants, architects, planners and politicians work together to form the world in which we live every day.

In this sense, the territory covered by Eterotopia is a palimpsest1 or manifesto, revealed in inscriptions and shavings, one on top of the other in order to form the complexity of the stories it tells us. In this regard feminist thinker Donna Haraway says: “It is important to understand what arguments we use to think about other arguments; it is important which stories we tell to tell other stories; it is important to understand which knots tie other knots, which thoughts think thoughts, which descriptions describe descriptions, which bonds weave bonds. It is important to know which stories create worlds and which worlds create stories.”2

It is equally important to think about which places other places dream of, which is basically how heterotopias are generated.3 Eterotopia La Maddalena has been mirrored or reflected in distant lands, like a remote history, and dreamed of in virtual, international waters.Hence, La Maddalena is both a local and international reality, which lends itself to the observation of problems related to its specific territory, but which is also an excellent case study of global phenomena, which are reflected in infinite parallel in other parts of the globalised human colony.4

La Maddalena is both a local and international reality, which lends itself to the observation of problems related to its specific territory, but which is also an excellent case study of global phenomena.

Through the lens of occupation we reread the territory of La Maddalena as a hyperobject, in the same way that Alexander von Humboldt modelled the Chimborazo volcano for his precursor studies of modern ecology. The themes analysed return the multifaceted picture of the complex stratification of the archipelago. By introducing eight insights, we sought to bring back the importance of acting on the complexity and layering of places in contemporary times.

Outposts

Through a process expressed in different phases and by the will of different subjects, La Maddalena Archipelago has seen the creation of a rich system of military fortifications on its territory. Today it is not only an important historical heritage site, but also a remarkable example of how architecture can be integrated into the landscape with an admirable process of camouflage.

The military architecture of the archipelago - a product of logics subservient to strategy - paradoxically succeeds in raising questions about the harmony of architecture with the landscape, morphological integration and the use of local resources. It does so in an era in which any attempt to protect the environment is a priority that conflicts with the desire to occupy, settle and exploit.

The expression "architectures that defend the territory" has a dual semantic charge. On the one hand it recalls the original function of these artefacts, and on the other it suggests a reinterpretation of the role of the fortresses of La Maddalena Archipelago, called upon to be an example, a historical memory and a point of arrival and reflection, no longer for control of the territory but for its care.

The military architecture of the archipelago paradoxically succeeds in raising questions about the harmony of architecture with the landscape, morphological integration and the use of local resources.

Tabula Rasa

In 1972 the Mayor of La Maddalena noted in his diary: “Mr Cossiga (former Italian prime minister and president) called me at home at 10.30 reporting this communication: The Americans intend to set up in La Maddalena a logistics base, a ship-support facility for submarines, with 180 people. The logistic base would include a village, able to host up to 3,000 people, between military and families. C. asks me for an immediate answer, to be given today.”5

After a secret agreement between the Italian and the US government, NATO’s base-support was settled on the island of Santo Stefano. It became the most important military complex in the Mediterranean sea and one of the most complete storage centres attended by the whole United States Navy. For 36 years the presence of Americans in La Maddalena triggered strong debates. In 2008 the base was dismantled and the last ship sailed to other shores: some exalted, others cried. Without a doubt La Maddalena suffered a negative backlash: between the military and their families, four thousand Americans lived on the island; thousands of people rented houses, ran the infrastructure, provided jobs and fed the local economy.

The presence of the American Marines supported the economy by affecting La Maddalena’s society and then left a hole in the territory that has never been refilled. The architectures that remain to witness are warnings of a project that embraces the logics of tabula rasa, by overlapping the territory without committing itself to dialogue.

The pedestal of the statue of liberty

The rare hardness of the granite present in the territory of the archipelago makes it an extremely valuable resource. Since the end of the 19th century, the extraction of granite has led to intense migratory movements in the archipelago of both stonemasons coming from the rest of Italy to the islands and granite that has been quarried at Nido D'Aquila and Cava Francese. Over time this granite travelled to distant lands, becoming the raw material for works of architecture and engineering all over the world. Examples include the colossal monument at Ismailia in Egypt, made from over two hundred tonnes of La Maddalena granite, and the monument for Guzmao of Santos in Brazil. Legend says that even the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty was carved from this prodigious granite, although there is no historical evidence of this.

Today, most of the quarries remain unused; some are exhausted, others have been rendered financially unviable due to foreign competition. The quarrying infrastructures have left La Maddalena with an important social and landscape legacy: the abandoned granite quarries are presented in the area as settings for new uses, new landscapes to be discovered, modern architecture in reverse, bearing witness to the archipelago's history.

The abandoned granite quarries are presented in the area as settings for new uses, new landscapes to be discovered, modern architecture in reverse, bearing witness to the archipelago's history.

Insularity

The island of Caprera is entirely included in the La Maddalena National Park, a protected marine and terrestrial area of national interest. Its pinewoods, the scrub, the wetlands and the coasts represent a great environmental richness but they also constitute a severe constraint on the fruition of its resources. The restrictions about its delicate naturalistic heritage and the regulations governing access are likely to jeopardise the enjoyement of the island itself.

The road bridge that links Caprera to La Maddalena, built in 1890 by Officine Savigliano of Genoa (at the time it was a swing bridge that allowed boats to pass through) was replaced by a Bailey bridge by the US Navy: this is still the only access to the island and it’s characterised by“selective transit”, meaning that only small boats can pass through it, preventing the entire circumnavigation of the island and limiting the routes available.

The isolation of Caprera is played out on different levels and the bordering agents rise to foreclose exploration to visitors in hidden zones.

The Failed Conquest

The 2009 failed G8 summit on La Maddalena put the spotlight on the island, making it a dramatic national case of bad governance. More than ten years after this episode, due to the fraud and complications surrounding the use of the former Arsenal area on La Maddalena, the regional administration is still having to deal with the consequences of failed post-event development strategies and an architectural legacy created to serve functions that never settled in the redeveloped area.

The Arsenal has been a great resource for La Maddalena, supporting the island's economy and social and identity development. Modifying this perimeter is, urbanistically and architecturally speaking, difficult to reverse. Moreover, the entire area is today unused and due to its immobility is inaccessible to the public, making any attempt to re-appropriate an area adjacent to the city centre impossible. Yet there are numerous opportunities that can be generated from this failure. The complexity of managing this complex is well known, but so is its potential.

Human Impact

La Maddalena has always been defined as a paradise on Earth starting from the first visitors who landed on it and it is still today a tourist destination in continuous growth and of international fame.6 The anthropic load makes the island suffer as it is condensed in the summer months to create a use, and often abuse, of the seasonal territory. It is an expanding phenomenon that threatens the preservation of the landscape in its most fragile aspects. The chronic nature of this presence also echoes the use and development of the urban fabric of the town centre which comes alive and changes according to the needs of this intermittent occupation.7

With the closure of the NATO base in 2008 - which had made the local economy flourish since 1972 - the archipelago was forced to reinvent itself by investing in tourism, but also generally in the tertiary sector because it was no longer strictly dependent on economical, political and military constraints.

It is undeniable that La Maddalena must look to a future in which tourism is its strength, and no longer an oppression both for the local community as well as for the environment. In this sense, sustainable tourism should undermine the stillness of postcard images through humorous and perceptive explorations of the territory.

Sustainable tourism should undermine the stillness of postcard images through humorous and perceptive explorations of the territory.

Another Nature

The natural landscape of La Maddalena is known for its white beaches and crystal-clear sea, but it also tells its beauty through its chaotically disordered granite landscapes, endemic and allochthonous flora, and the shaping force of the sea and wind. La Maddalena has conserved its wild nature in a unique way: thanks to its natural isolated conformation, a large number of endemic species still survive and constitute a great wealth, accounting for a quarter of Sardinia's natural diversity. Nevertheless, the human presence has modified the original landscape, importing new biological species or shaping its appearance, sometimes in a harmful way. The importance of its conservation was made official in 1994 when the entire land and sea territory of the archipelago was inscribed in a National Park.

The strict rules imposed by this condition are necessary to ensure that La Maddalena's natural heritage is not in danger of being damaged, but at the same time they constitute a strong limit for the use, appropriation and modification of the territory. The new frontier for the archipelago of La Maddalena is to create new alliances between humans and non-humans living within the perimeter of the Park. In order to avoid the embalming of the territory to which an overly conservative legislature often leads, it is necessary to encourage simpoietic actions among species that lead to the decline of the anthropocene and mark the beginning of a new era.

The human presence has modified the original landscape, importing new biological species or shaping its appearance, sometimes in a harmful way.

Archipelago

The sea, that other space of connection and isolation, primordial placenta and custodian of complex ecosystems, watchful sentinel of its precious gems: the Islands. The Mediterranean Sea has been the cradle of ancient civilizations, which have intuited and exploited the immense potential of communication, exchange and knowledge.

Apart from La Maddalena island - where the main homonymic settlement is located - the Stagnali village in Caprera, and about twenty holiday homes in Santa Maria, the archipelago has been almost uninhabited. Consisting of more than sixty islands and islets of granite and shale, the archipelago represents a complex that is strictly interdependent on sea and land and constitutes one of the most evocative landscapes in the world for its morphology, floral and marine landscape. The sea could be a place of existence either opposed or complementary to the one on the land, but also a space for a new network to be settled. By interpreting a complex universe the role of mental representations is crucial.

From the act of imagining the marine territory a cartography emerges, narrating the archipelago through a new mythology that interprets the history, toponymy and identity of the islands and of the sea that compose the La Maddalena Archipelago.

Excerpted and adapted from Eterotopia, "La Maddalena. Atlas of an Occupation" (Quodlibet, 2022).

Bio

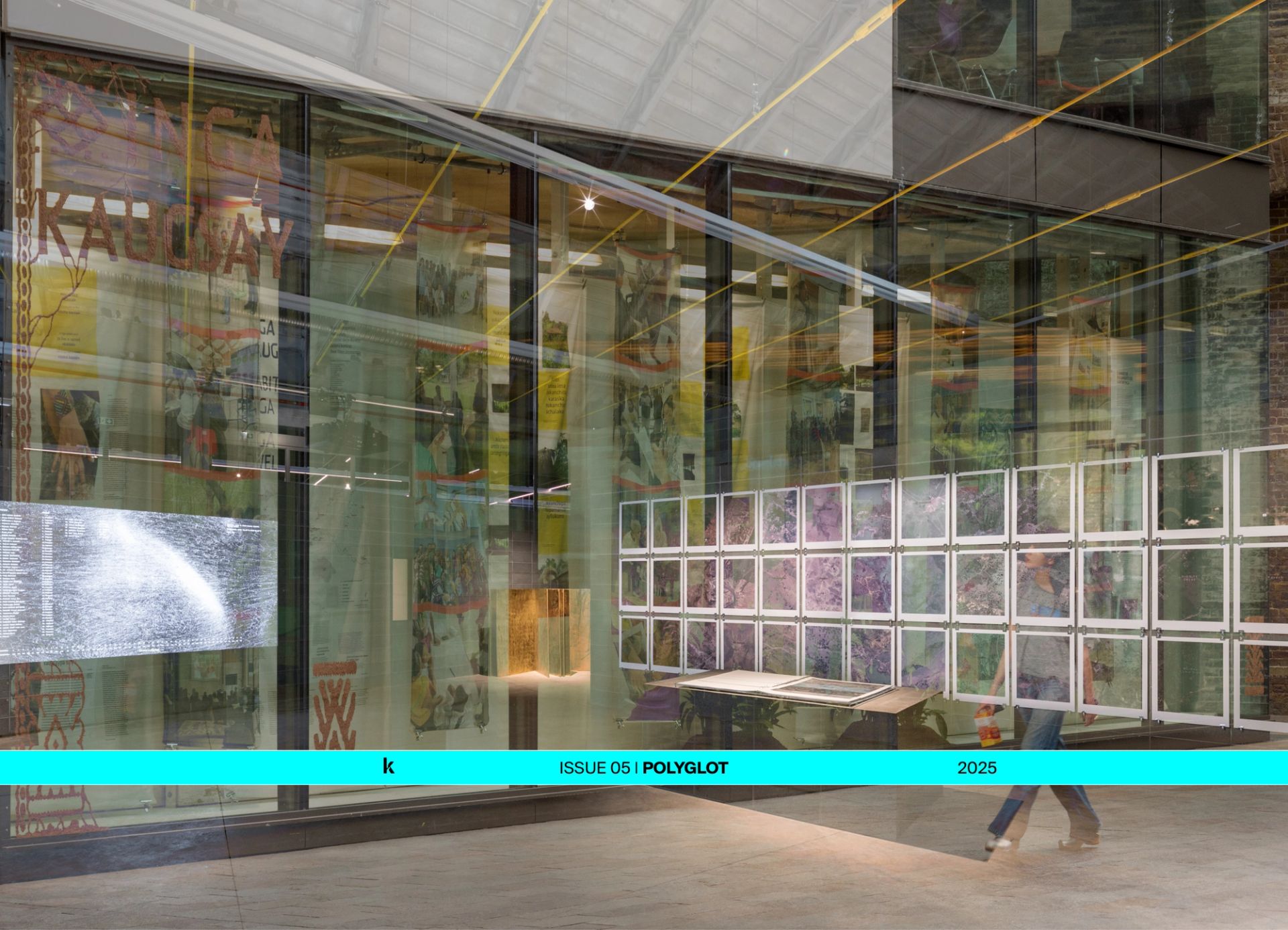

Eterotopia is a territorial research and practice group founded in 2017 by an heterogeneous group of Italian architects. It investigates the contemporary condition of the Italian territory and its complexity, interweaving manifest and imaginative conditions, sustaining the dignity of what defines the immaterial heritage of territories. Eterotopia's work has been exhibited at the Venice Biennale and at the Urban Center of the Milan Triennale. In 2022 they published "La Maddalena. Atlas of an Occupation'' (Quodlibet, 2022) that narrates a collective territorial laboratory organised in Sardinia in 2018. The team is composed by Elena Sofia Congiu, Matteo De Francesco, Carlotta Franco, Samanta Sinistri, Giuditta Trani, Mara Usai.

Giuditta Trani is an architect and musician from Trieste, Italy. At the intersection of these two practices, since 2018 she has been conducting research and projects that give space to voices and voice to places. She graduated at IUAV university of Venice in 2019, studied and worked abroad, in Geneva and Paris, taking part in international workshops and residencies as tutor and curator. With Eterotopia, of which she is co-founder, she works on the enhancement of the intangible heritage of marginal places in the Italian territory.

Notes

1 André Corboz, “The Land as Palimpsest” in Diogenes, 31(121), 12–34 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1177/039219218303112102

2 Donna Haraway, Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the chthulucene. (Durham: Duke University Press, 216), 27.

3 Heterotopias represent, in reality, the research space where our projects want to exist; we draw inspiration from the philosophical thinking of Michel Foucault to define those places different from the others but at the same time connected to them. It is thanks to their condition of diversity they can subvert the relationships to which they refer.In attempting to pursue a constructive transformation of reality, we exploit the conditions of these contexts as incarnations of anti-utopia: if utopia is effectively non-existent, heterotopias are existing places where achievements can be realised through real subjects and real processes.

4 “Relationality applies to urban and rural space, to land and ocean, as well as to various scales. It allows us to think the local and the global together. And it can be extended to notions of space and place in the oceans themselves.” in Stefanie Hessler. Prospecting Ocean. (Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Vienna. Published in association wtih MIT Press, Cambridge, 2019), 143.

5 Claudio Ronchi, “Quando vennero gli Americani”, ed. CO.RI.S.MA, Almanacco Maddalenino III, (La Maddalena: Paolo Sorba Editore, 2004).

6 In the 2015-2017 report of the province of Sassari, La Maddalena recorded a 100% increase in bookings and overnight stays in the island, as well as an increase by over 60% in ferry landings. See [link]

7 Thus the citizens' petition to establish a closed number of entrances to the island: by preventing the restricted number of tourists from having a harmful impact on the island's environment, the people of La Maddalena do not oppose the phenomenon of tourism itself, but rather the fact that it cannot be managed in a way that respects its environment. See [link]