Entitled “A Matter of Radiance”, the National Pavilion of Uzbekistan at Venice looked at the scientific and cultural relevance of the Heliocomplex “Sun”, a modernist scientific structure built in 1987 near Tashkent. Here, revered sociologist Steve Woolgar interrogates the very purpose of its monumental ambitions.

This essay was excerpted from A Matter of Radiance (Marsilio, 2025), edited by GRACE studio, the eponymous exhibition catalogue accompanying the National Pavilion of Uzbekistan as part of the 19th International Exhibition of Architecture at La Biennale di Venezia in 2025.

What is it, this strange thing, this big solar furnace (BSF)? This monumental structure that reaches far into the sky and dominates the landscape for miles around? This strange looking shield-like construction? What does it do? Where did it come from? And why?

In short, what is it?

Closely allied are a series of questions about its function and purpose. If we are asking what is it, we are also asking what is its purpose. What is the BSF for? Did it once and does it still have a purpose? So, what was this thing meant to do, and does it still do it?

In short, the question “what is it” prompts the question: does it work?

The BSF is an especially interesting object because it prompts a cacophony of these kinds of questions. Much of the time, especially with familiar everyday technologies — the car, traffic lights, the washing machine — we do not question; we take for granted what they are and what we expect them to do. Our culturally ingrained assumption is that things should work, and it is a disappointment or inconvenience when they do not. The extent to which these expectations are culturally embedded is highlighted by considering the opposite point of view. My uncle, for example, would say that his car “sometimes works!!” Such an eccentric view poses a striking inversion of our routine expectations about technology.1

In this essay I explore the opportunities and possibilities in addressing these BSF inspired questions. To do so we need something of my uncle’s inverted thinking. And to obtain this I draw on some research themes in Science and Technology Studies (STS). STS is a large multidiscipline which has grown substantially since its origins in the 1970s. In simple terms the commitment of STS is to expose the social, cultural, and political factors involved in the genesis of scientific knowledge and in the design, production, and impact of new technologies.2 STS is controversial because it offers a direct challenge to traditional, objectivist theories about science and technology. For example, early work in STS undertook ethnographic investigations of laboratory practice to show that, by contrast with accounts in the realist philosophy of science, scientific facts emerge as the upshot of contingent processes of social construction (e.g. Latour and Woolgar 1976). In other words, scientific knowledge is not a straightforward reflection of the way the world is. The knowledge we generate could always be otherwise. STS conveys a form of analytic skepticism about claims to knowledge and representation which has become influential across many disciplines and subjects.

"In other words, scientific knowledge is not a straightforward reflection of the way the world is. The knowledge we generate could always be otherwise."

As with scientific knowledge, STS similarly demonstrates that technological products are not the straightforward extrapolation of technical constraints nor of preceding technical achievements. Instead, certain prevailing social and cultural factors shape the outcome. In principle the resulting technology could always have turned out otherwise. Determinations of what the technology can or does do are similarly contingent. Whether and how a thing works is the complex upshot of relations between multiple actors.

It is axiomatic to early work in social studies of technology that an achieved design, the final product of development and construction, embodies key prevailing social, cultural and political forces. Famous STS examples include the social history of bicycles (Bijker and Pinch 1984). At each step in the ongoing development of the modern bicycle, different design decisions were influenced by “nontechnical” factors. For example, just as designers were looking for a frame for a two-wheeled machine, the manufacturers of rifle barrels found themselves without a market at the end of the Franco-Prussian war. The upshot was the production of the metal tubular design for bicycle frames. So, we can say that modern bicycles work in virtue of the cessation of a significant European war!

In particular, the variant of STS called Actor Network Theory (ANT) proposes that a scientific fact, or a technology, is the network of allies which make up the phenomenon (e.g. Latour 2007). Importantly, these allies comprise both human and non-human entities. The “fact” of global warming, for example, is a heterogeneous network of results, observations, reports, publications, political institutions, funding decisions, government declarations, scandals, measurement techniques, existing results, the properties of ozone gases and many other entities; that is, in addition to the scientists, observers, journalists, commentators, etc. which appear in traditional analyses. Of particular significance is that the strength of the (claimed) fact, or the efficacy of the technology, is no less, and no more, than the work needed to make the allies desert and thereby dissolve the network. Hence, “climate deniers” have their work cut out to contest such a huge, robust configuration.

Think of the BSF as an object. It is commonly assumed that most objects and entities (perhaps especially those outside the art world) have some kind of a purpose. Or at least, that it is possible to identify a purpose. Objects without a purpose are rare.3 When one visits antique dealers one is invariably offered a story attached to the objects on display. The object lives in and with the story, the purpose, of which it is part. To interrogate this phenomenon, I set myself a hobby of searching for objects “without a purpose.” The difficulty of the task is underscored by the fact that after many years my collection comprises just one such object! I use this object in a teaching exercise to surface the uncertainties we suppress and the processes of interpretation we deploy unthinkingly, as if for all practical purposes we “know” what the object is. By suspending the “obvious,” “apparent,” and “evident” nature of the object the exercise highlights the unnoticed work that routinely goes into making sense of it. With my teaching object students are drawn into investigations of “what it does” as a way of figuring out “what it is for” and hence “what it is.” We need to approach the BSF in a similar manner.

"The object lives in and with the story, the purpose, of which it is part. To interrogate this phenomenon, I set myself a hobby of searching for objects 'without a purpose'."

So, what do we know of the origins and contingencies of the BSF? The evidence is that it was conceived during the Cold War, at some point after the signing of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in Moscow on August 5, 1963; ratified by the United States Senate on September 24, 1963; and entered into force on October 10, 1963. The treaty prohibited nuclear weapons tests "or any other nuclear explosion" in the atmosphere, in outer space, and under water.

Interviews confirm that a considerable amount of networking, communication, and persuasion went into the original funding and commissioning of BSF after the Test Ban Treaty. In the terms of ANT, as described earlier, this amounts to the assemblage of a large number of disparate entities which together support the construction of BSF. ANT asks how did the various entities come into alliance, how were they recruited to the cause, how were the interests of each enrolled or modified to contribute to the emerging network? In BSF, these entities included various individuals in the political and scientific hierarchy in the USSR, the outcomes of various bureaucratic and administrative committees and, significantly, the imaginaries of The West, NATO and the USA. In the telling, various individuals feature as especially persistent and thus heroic players in making links and recruiting others to the cause [interview Parpiev]. Importantly, the BSF actor network is a heterogeneous mix of both human and non human entities. For example the meetings, the committee reports, the messages and letters, the mirrors capable of reflecting sun’s rays, the protective film necessary to ensure their optimal reflection and so on. The son of the original director of the heliocomplex tells how his father traveled to visit the French installation (interview Azimov 29.01.25.m4a), thereby recruiting a further ally.

Of course the particular nature and strength of each alliance is important. One former director of BSF, Ilkhom Pirmatov, recounted that his visit to the French facility was highly constrained.

IP: There they have the same opportunities as we do. Not more. They do not publicise what they do and they don’t let people in. There is hardly any access.

Q: I know that your colleagues, and maybe you, went there in the mid-1970s and saw everything before the construction of the furnace in Uzbekistan.

IP: Right, we traveled there, but that doesn't mean they allowed us to familiarise ourselves with the whole site. They showed us the facility itself and how everything works, but what they melted there and what they use these results for is another matter. They did not even allow us to measure any infrastructure. We could look as much as we liked but that was it.

The accomplished combination of elements constituted a temporarily robust actor network: the heliocomplex. But over time the allies in the network started to desert. In particular with the collapse of the USSR, one crucial ally — the system for sending money between banks — absconded, so the BSF was left without funding. Other allies, the customers/clients for BSF work, disappeared, and many BSF scientists and workers left. Director Parpiev said “1,000 people left after the collapse of the USSR. The most important scientists moved to Russia.” By the 1990s the BSF was left semi abandoned, with “no scientific work after 1993.”

“The worst year” was 2016, “with only superficial scientific work.” By 2021 the BSF was quite dilapidated. Now, at a later date, architectural interests have entered the picture and the BSF has been deemed architecturally “significant.” Ekaterina Golovatyuk is an architect who works jointly with Gayane Umerova, heading the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, on the preservation of architecture built in and around Tashkent in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s, variously called modernist architecture, Tashkent modernism or, as it used to be called, Soviet modernism. She believes this valuable heritage was ignored for many years in the post-Soviet era and systematically erased worldwide. But now, especially since about 2010 she says, this heritage has begun to be reviewed, reevaluated, and its importance and relevance realised for today.

Ekaterina and colleagues compiled a broad registry of forty buildings, which they subsequently reduced to a list of twenty-three:

“that we think remained in pretty good, authentic condition, and we put those buildings on the monument registry, including the BSF. And we have started … a large study together with an international group of restorers, researchers, architectural historians. Similar processes of re-evaluation are happening all over the world, not only in Uzbekistan.”

We can understand the effort to assess, preserve, and protect the buildings as a move in reconfiguring and strengthening the BSF actor network. It would become a different object in virtue of the recruitment and involvement of different allies (it’s happening all over the world… a large study with an international group of restorers, researchers, architectural historians…). And this move came as a surprise to some members of the existing actor network. In recounting his approach by the architectural team, Odilkhudja Parpiev, director of the Tashkent center, expressed surprise that even the “laboratory” section of the complex was deemed architecturally significant:

“….about the listing of the building and the premises of our institute. I always thought that we were talking about the tower complex. The heliocomplex itself, that is the heliostats, tower technology, and concentrator, these are objects of modernism, high technology, and so on and so forth. But I did not expect our building to get in [to the architectural listing]. Our building, as we understand it, is a laboratory. A standard laboratory where scientific research is done. And suddenly it turns out that the building, not only the concentrator, the whole area, falls into this list.”

For the architects the project of restoring the significance of the BSF is to be built on diverse, pre-existing allies: architectural value, artistic components, historic events, the surplus emotional and cultural attachment to former Soviet buildings, their use in celebrations and as places to visit for recreation and leisure, their association with celebrities, and so on. But the current director had other potential allies in mind. When I asked how many visitors came to the BSF for cultural reasons he told me quite firmly that all visitors come out of curiosity for the science.

The recent ambition to make the BSF the spearhead of a “Valley of Green Technologies" (VGT) can be understood as an attempt to constitute an alternative actor network. In futuristic depictions of the VGT, new actors are explicitly identified. Some prominence is given to potential “collaborations with China, USA, Russia, Spain etc,.” Will one particular actor network win out? Much depends on what ends up counting as “working.” “Working” might mean achieving environmentally efficient high-temperature experimentation in the development of hydrogen and nano technologies, in collaboration with international partners. Or “working” could mean a highly valued architectural and artistic restoration, internationally recognised as establishing the architectural significance of modernism. Can alternative visions of the BSF stand side by side?4 In principle, yes. In practice, it depends on the extent to which the different networks can share allies. Are there resources to persist with the apparently endless task of repairing and improving the many mirrors? Or are these resources better invested in preserving the facades of the complex?

Think of the BSF as a text. A technology is a text which can be read in many ways. Or, we should say, it can in principle be read in many ways. The rhetorical achievement of some texts is that they can or should only be read in one way. Of course, the text itself doesn’t achieve this. It is rather in virtue of the community it performs that certain readings prevail. And if it’s useful to think of technology as a text then it might be equally useful to think of text as technology. Our own texts about the BSF can be understood as technologies with certain effects inbuilt.

And maybe here is a clue to the fecundity of the BSF. It affords multiple readings. (“Afford” is a dreadful term because it tricks us into thinking that a thing has some given, inherent, essential quality). Are some objects/technologies, particularly the BSF, inherently flexible, inherently generative of multiple readings? De Laet and Mol (2000) seem to think so in their discussion of the Zimbabwean bush pump. In that account, the engineer responsible for the pump is a hero for designing and creating a technology which allows multiple fruitful adaptations. The case of the BSF seems rather different. It is not that the BSF has an inherently flexible, adaptable core characteristic. Over the course of its short history, the BSF has been constituted through different actor networks. Its (current) ambiguity and ambivalence reflect the situation that no one actor network is (yet) dominant.

We see something similar in the popular reporting and nomenclature associated with the BSF. I have been referring to our object as the Big Solar Furnace (BSF). But in various documents and interviews it is variously described as the Heliocomplex, the Sun Center, the Solar Furnace, and the Big Solar Furnace. If one asks ChatGPT to write a short account of the “Big Solar Furnace,” it mentions only the installation in Odeillo, with no mention of the one in Tashkent. We are told that the Odeillo construction, “harnesses the power of the sun to produce high temperatures through concentrated solar energy. It consists of an array of mirrors, known as heliostats, that focus sunlight onto a central receiver, generating temperatures exceeding 3,000°C. This monumental project has been instrumental in advancing solar thermal energy research and has applications in various fields, including materials science and energy production. The furnace is not only a testament to renewable energy technology but also serves as a hub for scientific research and innovation.” (ChatGPT report requested 11022025) If we ask ChatGPT specifically for an account of the “Solar Furnace in Tashkent,” we are told that it is “a significant installation that utilises solar energy to generate high temperatures for various industrial applications. This facility employs a system of mirrors to concentrate sunlight onto a focal point, achieving temperatures that can reach up to 1,000°C. The Tashkent Solar Furnace not only supports research in solar technology but also aids in developing materials and processes that benefit from high-temperature applications. It represents an important step in harnessing renewable energy resources in Central Asia, contributing to sustainable development and energy efficiency.” (ChatGPT report requested 110225)

Of course, ChatGPT, like other digital resources, can be very inconsistent and unstable in precision. But the variations are nonetheless worth noting. ChatGPT assigns a different achieved temperature to each installation: 3,000°C in Odeillo; 1,000°C in Tashkent. This difference was contested by the Tashkent director in interview, as arising from a limited consideration of the size of surface area which can be heated. Neither ChatGPT account mentions the putative Cold War origins. More interestingly, the original historical rationale for construction is now reworked and overlaid with contemporary issues of environmental and energy concerns: “The Tashkent Solar Furnace was constructed in the 1980s and represents a significant achievement in harnessing solar energy for practical applications. It was developed during a time when there was a growing awareness of the need for alternative energy sources, particularly in the context of environmental concerns and energy shortages…..Additionally, the furnace has played a role in educational programs, raising awareness about renewable energy and its benefits among the local population.” (ChatGPT report requested 110225, my emphasis)

As already suggested, the history of the BSF is deeply bound up with politics, in the broadest sense. We need to note, however, that the reading of social and political influences from a technology is a perilous task. It is also bound closely to, if not completely dependent on, specific contingent readings of technical capacity. And yet, in principle, the reported technical effects of a technology/ object are just as uncertain as are the reported political influences. This is well illustrated by the case of Moses’ bridges. It was famously alleged that the overpasses designed and built by Robert Moses on the Long Island freeways in the USA during the 1950s and 1960s exhibit racial bias (Winner 1980). It was alleged that the bridges were made deliberately low as to prevent the passage of buses traveling down the highways to leisure areas such as Jones Beach. Since blacks and poor people depended on bus transport this shows, it is argued, that the bridges embody the racial bias of their designer.

The problem is that the basic premise of this example — the “fact” that the overpasses prevented the buses traveling down the highways — turns out to be questionable. It is not clear that the bridges ever did prevent the passage of buses. Rather their effect remains essentially unclear (Woolgar and Cooper 1999).5

The claim about the political factors involved in the Moses bridges’ story — the racial bias of the bridge designer — depends on a definitive account of the bridges' technical capacity. I am struck by the parallels with the BSF. The design and construction of the Tashkent solar furnace is understood to embody political fears about its rival NATO installation in France. In the BSF case political concerns similarly depend upon, and are heightened by, definitive attributions of technical capacity. What was the French installation achieving and how could the BSF match or exceed that? In this context, claims about, for example, whether, when, and how the BSF could achieve 3,000°C are likely to be more aspirational than factual.

Clearly then, throughout everything, we need to retain a certain skepticism as to what counts as “working.” Responses to questions about the (current) technical capacity of the BSF are often cast in terms of what I call “futurification.” By which I mean the depictions of the capacities, effects, and impacts of a technology are almost invariably described as matters that can only be determined in the future. This is especially apparent in current questions about the state of AI. Does AI fully mimic human intelligence? Can AI substitute for human creativity? No, but we are getting there, it is not far away. Rappert (2001) speaks of this kind of deferral in relation to technical capacity. Does the use of pepper sprays by police officers constitute a harmful danger to members of the public? In his study, no one involved seemed able or willing to answer this definitively. Instead, it is left up to the “bobby on the beat” (the policeman on the street) to use discretion and make decisions in the moment as to the effects of using the spray. In the same way questions about the operation and achievements of the BSF are similarly answered using futurification.

There is a lot of talk about nano tubes, but it is not clear whether this work is actually being done now. I asked, so what can this machine do? Have you done it? The answers are always no, no. Maybe in two years.” (Interview Ekaterina Golovatyuk 120225)

Can we say that the BSF was abandoned? The term implies high drama. The popular TV series Abandoned Engineering (from 2021, British television) states that “What were once among the most advanced engineering projects ever undertaken now lay in abandoned ruins around the world. Experts explore why some of Earth's biggest and most mysterious constructions were built and what brought about their downfall.” The series dramatises the discovery of neglected projects, overlaid with eerie music and breathless narration. The rhetorical appeal is to the discovery of these unknown and neglected objects, rendered mysterious and strange, because their original purpose has been lost in time. Certainly, the BSF has endured a period of “semi abandonment.” The crumbling décor, peeling wallpaper, discolored windows, and outdated computer equipment of the 1980s (figure 3) signal a deterioration in the quality (and the absence) of allies in the failing actor network. There are stories of stolen parts and missing components from buildings: a literal abduction of material allies.

By contrast figure 4 shows the same control room refurbished and updated, redecorated and boasting updated IT equipment . A revived actor network? Interestingly, I am told of disputes over which parts of the BSF complex should be renovated, and how. I was told that only four people were currently employed in the Sisyphean task of substituting and aligning the mirrors. The scientists say that, in general, many more resources are needed for repair and maintenance. The architects are not happy that some funds are being used to quick-fix aspects of the buildings with low quality materials.

Can we say the BSF is now obsolete?

Images of the past and present of the BSF interrelate in complex and uncertain ways. In her study of how former industrial environments are interpreted and reinterpreted, Anna Storm (2008, abstract) shows how they often become “an arena for visions of the future in the local community, and, furthermore, how they are being turned into a commodity in a complex gentrification process. The places are given new value by being regarded as an expression of the overall phenomenon of reused industrial buildings, and, simultaneously, as a unique and authentic entity. In the conversion of the physical environment, the industrial past becomes relatively harmless to many people, because the dark and difficult aspects were defused in different ways. Instead, the industrial place was understood in terms of adventure, beauty and spectacle, which included rust from the past as well as hope for the future.”

"In the conversion of the physical environment, the industrial past becomes relatively harmless to many people, because the dark and difficult aspects were defused in different ways."

- Anna Storm

While it can hardly be said to be undergoing a process of gentrification, or perhaps only marginally through partial efforts at minor refurbishment, the BSF can be understood as being given a new value. Many of Storm’s other descriptors seem apposite: it is, in virtue of efforts of the architects’ consortium, initiated and supported by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, becoming a potential expression and celebration of Soviet modernist architecture. At the hands of (promised) investment in its scientific future it is simultaneously being positioned as a unique and authentic place of science. It is to be understood as a place of “adventure, beauty and spectacle” through aspirations to make it a beacon of pioneering environmental responsibility, intended to become a pivotal component of the aforementioned Valley of Green Technologies by 2030.

There is, though, one additional prominent question about the BSF. I have suggested that the question “what is the BSF” is tantamount to asking what it does (or did). Whereas Anna Storm’s industrial heritage sites often have relatively straightforward narratives about what they were originally intended to achieve, the origins of the BSF have some mystery attached. The mystery is exacerbated by how little is known and how few people have even heard of the BSF. My own straw poll found hardly any academic colleagues had heard of the BSF. Even among academics specialising in Soviet industrial installations, few were familiar with it. The original secrecy contributes to this. But it is not as if the (less secret?) French installation is any better known.

All these considerations are in play. But this also means that they are in tension. So, if we return to our initial animating question, we begin to understand why there are so many answers to “what is it?” A decaying, obsolete memory of Soviet cold war anxieties? A monumentalist celebration of Soviet science? An innovative way of generating super high temperatures? A means of testing the resistance of materials to nuclear attack? In direct competition with a (more or less) similar structure “built by NATO” in France? A way of developing materials for spacecraft that can withstand re-entry into the earth’s atmosphere? A paean to environmentalist energy production which eschews reliance on fossil fuels? A key to the future production of nano tubes? A pointer to future long-term dependence on hydrogen energy sources? Some or all of these answers, or some in combination?

Oh Big Solar Furnace!! I think I may be in love with you! Not for your looks, sorry. You may have seemed wonderful and imposing in the beginning. You may once have exuded striking virility. But these days, let’s face it, you are looking pretty shabby. Nor am I in love with your much-vaunted aspirations and ambitions: maybe 3,000°C was never achievable? Nor am I susceptible to any attachment to Soviet modernist architecture. I do not share the affection — apparently surprisingly widespread in many former Soviet states — for modernist Soviet monumentalism.

"I do not share the affection — apparently surprisingly widespread in many former Soviet states — for modernist Soviet monumentalism."

No, rather I love you for your generative power, your ability to prompt deep questions about what we take for granted about science and technology. While all the while you stand there in mute silence! In your enigmatic, brutish materiality, you generate profound ambivalence. A merely material structure that provokes a mass of puzzles and reflections on the very nature of knowing and acting in the world.

We have explored some reasons for the ambiguous status of the BSF. Its ambivalence arises from and speaks to multiple and overlapping efforts at interpretation and intervention, in short, competing actor networks. If the BSF receives its planned physical and material upgrade, but no further actors come on board and the furnace does not actually work as intended, the beast will most likely just museify. If, on the other hand, the BSF also establishes its desired international collaborations, it can perhaps take steps toward achieving its originally envisaged scientific status. The interesting remaining question is this. If or when the BSF becomes thoroughly renovated (materially) and/or repositioned (socially and culturally) will it lose its paradoxical allure?

I, for one, hope not.

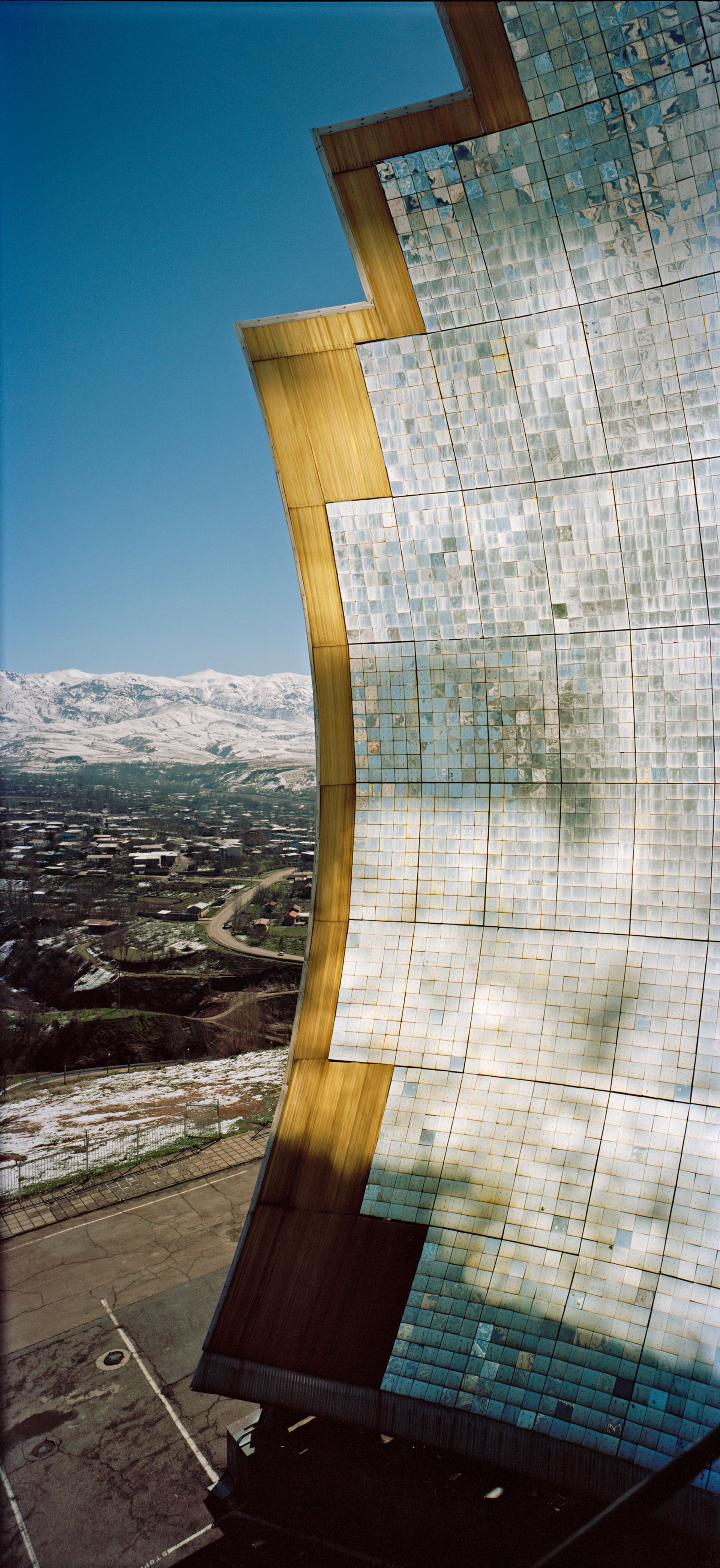

Heliocomplex Sun, concentrator, Parkent, Uzbekistan, 2021. Courtesy of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF). Photo: Armin Linke.

Bio

Steve Woolgar is a pioneering sociologist; he is an Emeritus Professor at both Linköpings University and the Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford, in the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS). Woolgar published Laboratory Life: the construction of scientific facts (Princeton, 2nd ed. 1986) in collaboration with the French sociologist Bruno Latour. He has published widely in science and technology studies, social problems and social theory, researching topics as diverse as virtual society, neuromarketing, globalization, ontological disobedience and academic evaluation.

Notes

1Yet this is perhaps a much healthier attitude to technology: don’t expect too much; always be surprised (and grateful) when the thing actually works.

2This summary description of basic STS sensibilities underplays that STS comprises a vibrant and healthy assemblage of many competing, sometimes warring, perspectives and factions.

3Cf. Michel Tournier’s Friday (1997), when at some point Robinson wakes up and time has stopped (because he forgot to reset his sand clock). So, he starts observing things (tables, chairs) not in terms of their function (which implies use in time) but in terms of their spatial and aesthetic qualities, as if they had no purpose. Thanks to Ekaterina Golovatyuk for this.

4And, for advanced readers, to what extent will events like the Venice Biennale, to which this essay is a contribution, itself prove an effective ally?

5Garutti and Mihandoust (2016) have created a brilliant film exposing the ambivalences and uncertainties around the preventive capacity of the bridges.

References

de Laet, Marianne, and Annemarie Mol. 2000. “The Zimbabwe Bush Pump: Mechanics of a Fluid

Technology.” Social Studies of Science 30 (2): 225-263.

Garutti, Francesco, and Shahab Mihandoust. 2016. “Misleading Innocence (Tracing What a Bridge

Can Do).” Documentary film, Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Latour, Bruno. 2007. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford

University Press.

Law, John. 1994. After Method: Mess in Social Research. Routledge.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. 2nd edition, 1986. Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific

Facts. Princeton University Press.

Pinch, Trevor J., and Wiebe E. Bijker. 1984. "The Social Construction of Facts and Artefacts: Or How

the Sociology of Science and the Sociology of Technology Might Benefit Each Other." Social Studies

of Science 14: 399-441.

Rappert, Brian. 2001. "The Distribution and Resolution of the Ambiguities of Technology, or Why

Bobby Can’t Spray." Social Studies of Science 31 (4): 557–592.

Storm, Anna. 2008. Hope and Rust: Reinterpreting the Industrial Place in the Late 20th Century.

Stockholm Papers in the History and Philosophy of Technology TRITA-HOT-2057 E.

Tournier, Michel. 1997. Friday. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wales, Luke et al. 2017–. Abandoned Engineering. BBC TV series.

Winner, Langdon. 1980. “Do artifacts have politics?” Daedalus 109 (1): 121–136.

Woolgar, Sreve, and Geoff Cooper. 1999. “Do Artefacts Have Ambivalence? Moses' Bridges, Winner's

Bridges and Other Urban Legends in S&TS.” Social Studies of Science 29 (3): 433–449.