The subject of architectural education raises its head above the parapet every so often, and is usually met with a barrage of critical opinion.

Who teaches the teachers?

Who decides what to teach, and who is learning from whom?

What exactly are we training to be?

Against a backdrop of precarity and student debt, can theoretical knowledge be as important as professional experience? How can we attempt to challenge an evolving discipline, when our teachings are often rooted in the tenets of (European) Antiquity? How do we alter the problematic dynamics of the classroom, in an already elite and privileged profession?

It may be argued that the pace of change in architectural education is more agile than the profession itself.

Even as these questions and more pour forth, it may be argued that the pace of change in architectural education is more agile than the profession itself. True, institutions are reluctant to allow for this agility — yet it is clear, since at least the COVID-19 pandemic, that the field of pedagogy has been the site of incredible innovation that demands attention, powered in most cases by educators’ inventive dedication and care.

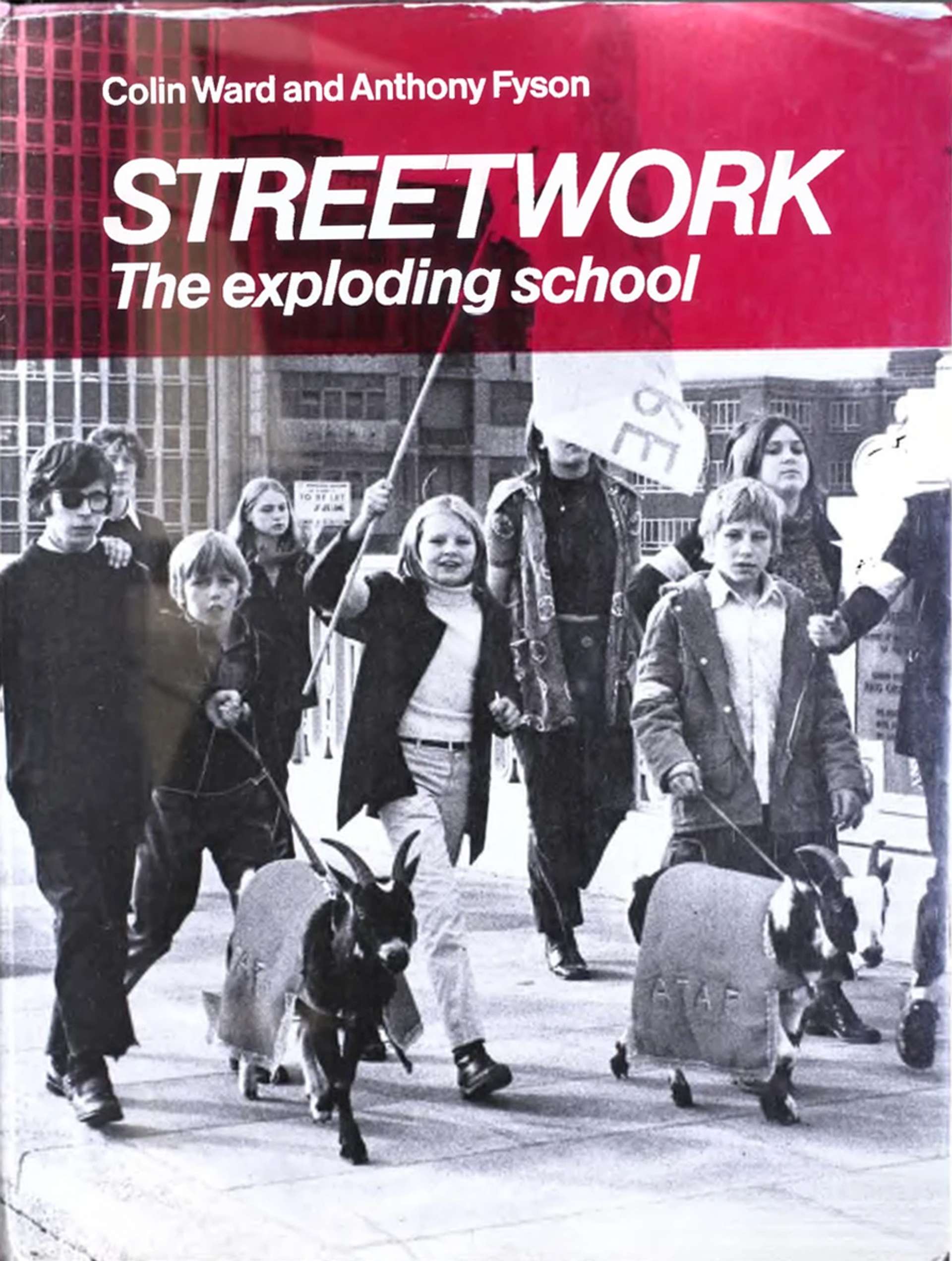

In this line of thinking, we take our inspiration from the planner and “gentle anarchist” Colin Ward (1924-2010), who wrote dozens of texts on education, advocated for greater informality and the integration of non-traditional spatial contexts as learning environments — seeing the city as a sandbox, and training teachers to look for alternative classrooms across town and country. Ward held a lifelong insistence on the need to disrupt and transform dominant practices by ‘bringing freedom’ to ‘ordinary schools’ — a view which rings true when considering the lack of access and parity in design and architecture education today.

Technology and its integration into the study environment ceased to be optional, and the abiding effects of distanced, screen-based learning, not to mention the attendant social isolation are not yet expunged. Likewise, certain ideas borne of necessity or urgency are beginning to take root. Firstly, there is the incontrovertible recognition of mental health issues, and the need for consideration for pressured students and staff alike. The long-held bravado of surviving all-night modelmaking sessions and humiliating reviews feels deeply passé for today’s architecture student, and is more likely to lead to cancellation rather than admiration of their instructor.

Substantially more noise has been made for the decolonisation of the educational institution than there has in an awfully long time. However fractional and fragmented they may seem, the steps made in the direction of decolonising the curriculum, faculty and pedagogy are both more numerous and indelible than ever before in the history of architectural education. The inequalities in access to, and success within, the architectural profession — along lines of race, class and gender to name just a few factors — have long been irrefutable. Lately, it would appear that a majority of global educational institutions — certainly those which have traditionally held influence and power — have been obliged in some capacity to address these factors.

New Rules for School is interested in those who are piercing the bubble, expanding the fringe, drawing from diversity, inventing new glossaries and expanding the contexts in which we learn and teach architecture.

And yet therein lies a contradiction: how does one truly decolonise the high privilege of an expensive and extended period of education, in training for an historically elitist and exclusive profession? Of course, this collection cannot hope to cover the breadth of innovation in the field — we hope to instigate, rather than define, discussions of pedagogical creativity across the many regions and scales not addressed here. For this issue, we would linger on the fringes of the study hall. While the academic traditions and history of architectural education remain valid subjects of enquiry, New Rules for School is interested in those who are piercing the bubble, expanding the fringe, drawing from diversity, inventing new glossaries and expanding the contexts in which we learn and teach architecture.

From Streetwork: The Exploding School, Colin Ward & Anthony Fyson (Routledge and Kegan Paul, London: 1973)

In this issue, we collect and conduct candid conversations with those bridging the margins and centres; those who are stretching not only what we talk about in architecture school, but also who we address and where we situate ourselves when we talk about architectural thinking, learning and teaching:

We begin with The Architectural Thinking School for Children, founded by art historian Elena Karpilova and architect Alexander Novikov, an extraordinary project using “architectural systems thinking” as a mode for young people to decipher the world.

Exploring gameplay as an avenue for architectural form finding and development, many practitioners work across virtual design and material construction. Francisco Veiga Moura expands on the work done at François Charbonnet and Patrick Heiz's Studio Voluptas at ETH Zurich, that brings students of game design and architecture together, utilising theories of ‘adult play’ to realign classroom dynamics.

‘Reconstructions’, led by Marie Louise Richards, is an ambitious and — yes, really — radical programme at Stockholm’s prestigious Kungliga Konsthögskolan (Royal Institute of Art), which deploys critical Black feminist, queer and Afrofuturist methodologies in the academy and deprioritises productivity.

Marija Maric, David Peleman and Cesar Reyes discover a mode of reparational spatial practise through a (truly) close-looking study of soil, at the University of Luxembourg — a scale of concern challenging the vocational orientation of students and the broader architectural community.

Facing south, two independent schools of architecture compare notes: Maira Rios and Carol Tonetti of Escola de Cidade in São Paulo talk about new collaborations with Rohan Shivkumar of the Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute in Mumbai.

Addressing the labour of pedagogy is an unglamorous but necessary urgency. With careers spanning multiple prestigious and forward-thinking institutions on both sides of the Atlantic, distinguished academics Shannon Mattern and Marina Otero get real about the exhilaration and the sheer work of teaching interdisciplinarity.

Discussing the relationships between architectural education and practice, Tatiana Bilbao, Elisa Iturbe, and Ayesha Ghosh highlight their fundamentals in intertwining professional practice and pedagogy and addressing architecture as a political act.

Pilar Finuccio (Center for Urban Pedagogy - CUP), Damon Rich (HECTOR urban design), and university professor Marcelo López-Dinardi discuss urban pedagogy, commoning practices, and the built environment. Urban pedagogy, participatory processes, and commons allow citizens to participate in decision-making to shape and manage cities.

Ross Exo Adams with Ivonne Santoyo-Orozco (Co-Directors of Bard Architecture) and Stephanie Lin, Dean of The School of Architecture, discuss the relationships between pedagogy, professional practice, and politics. Bard Architecture and The School of Architecture are two experimental architecture programmes that attempt to set new standards and methodologies through innovative pedagogical approaches.