Water Parliaments, the Catalonian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale addresses and reimagines architecture as a multispecies collaborative practice reflecting the interdependence of humans, non-humans, and water systems. Here, several extracts from the accompanying publication illustrate the cultural, technical and radical vocabularies associated with water.

The texts below are excerpted from 100 Words for Water: a Vocabulary (Lars Müller Publishers, 2025) edited by Eva Franch i Gilabert, Alejandro Muiño and Mireia Luzárraga, on the occasion of the 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia in 2025.

Words and Worlds | Eva Franch i Gilabert, Mireia Luzárraga, Alejandro Muiño

Words do not merely describe the world – they actively shape it. Every architectural idea, every cultural shift, begins with language, with new terms emerging precisely at the threshold where existing words fail to encompass new realities.1 In an era defined by unprecedented environmental urgency, where our very relationship to water is undergoing profound transformation, the necessity for a new lexicon becomes not merely linguistic, but epistemological.

The climate crisis, as the United Nations starkly states, is fundamentally a water crisis. Yet our existing vocabulary – rooted deeply in outdated paradigms of dominance, extraction and control – proves inadequate to articulate the emerging complexities and urgencies surrounding water. Modern western terminology limits our ability to envision and therefore enact alternative relationships with the world’s most vital resource. If we are to reimagine our future with water, we first must redefine the language we use to describe, interpret and engage with it. [...]

To engage with this vocabulary is to participate actively in reshaping not just how we talk about water – but how we live with it, share it and protect it, in a collective quest for hydric justice.

Datawater | Liam Young

Once, water was the first condition of life. It cradled the first cells, lapped the banks of early civilizations, was sung into myth as river, rain and sea. Datawater is water shorn of myth, stripped of its ancient covenant with the living. It does not belong to the biosphere but to the machinic. It is a liquid of circuits and turbines, feeding fiber-optic cabling not the tendrils of trees, drawn not by clouds drifting in the sky but the cloud computing humming in the vast halls of server farms. Datawater does not belong to us. A water that does not nourish roots or sustain flesh. It does not pool in cupped hands or sparkle in a heron’s eye. It is not drawn from well or stream for the hunger of the land. It does not sing in mountain streams or cradle the larvae of insects. It does not glisten on the skin of animals, nor quench the thirst of a dying man. It moves in pipes, not rivers, through the arteries of machines, sluices through the steel intestines of industry, drawn into vast industrial lungs, swallowed by power plants, exhaled in great ghostly plumes above data centers, where the servers flicker and whisper in the dark. It pools in containment basins, not in lakes where birds skim the surface. It has no place in the great cycles of nature; it does not wish to return to the sky, nor sink into the ground. It does not freeze into delicate lattices, nor burst forth in a spring.

It flows where people do not, behind locked gates and warning signs, through the cooling loops of power stations and the quiet corridors of server racks. It is drawn not to nourish but to dissipate, not to quicken life but to temper the heat of the artificial. It drifts through exclusion zones, through places where human presence is incidental, unnecessary or unwanted. It is a water that has severed its ties to life, it longs only for the warmth within our vibrating labyrinth of planetary machines. Datawater is the cold blood of the post Anthropocene, the water that cools the relentless, fevered thoughts of artificial minds, that keeps the heat of a billion computations from igniting. A water that no longer dreams of fish, nor ice, nor rain, that does not remember the glaciers or the monsoons, nor the salt of the sea. It is water that only knows machines, in pools black and still beneath the dead lights of a world we built, a world that no longer needs us.

Expanded Body | Christina Varvia

How much space does a body occupy in its lifetime? If we were to take a long exposure photograph from the moment a human is born until they die, then the space taken up by this body would include an average of 242.2 million liters of air,1 35 tons of food,2 as well as 62,400 liters of water.3 The expanded body is the body spatialised, it gives an account of the total sum of food, water, air, minerals and chemicals, the sought out and inadvertent molecules that journey through the body and that end up constituting it. It also includes all the human waste that ends up nourishing or polluting the earth’s land and water.

The numbers presented above consist of an average. In reality, the difference between the maximum and minimum space that a body may occupy varies significantly. One could say that this is the space of politics itself. In it, the categories of race, class and sex determine the shape of bodies. Multiple patterns of global injustice might be observed if one analyses who has access to three liters of clean potable water a day, versus half a liter. Yet more than a question of resource distribution in terms of quantities, this provocation sees the body also as a carrier; it is a plasma that holds other bodies, our symbiotic entities.4 Microbes, viruses, but also toxins, metallic particles and microplastics. If the expanded body is an articulation of substances, organisms and microecologies, collaborating or disputing one another, then the very delineation of which entities should be included and which excluded from this molecular intimacy is also a political act.5

This open definition of an expanded body offers some opportunity for advocacy on behalf of ecologies and non-human entities that share our bodily space. Rights of rivers and lakes, rights of clouds and rain, are also human rights because part of us is river and lake, cloud and rain. How then do we witness our material interplay and find political alliances within these ecological commons?6

Christina Varvia, Portrait of an Expanded Body. Still from Video. Courtesy of the Author.

Hydro-Engineering | Dorothy Tang

The act of transforming water from one form to another is hydro-engineering. It acknowledges that “wetness is everywhere”1 and water forms are embedded in the everyday landscapes we occupy. Water exists as surface water, groundwater, saturated soils or aquifers. It also defines space — watersheds are shaped by its flow, while rivers, lakes and oceans support diverse ecologies and resources. As a chemical agent, water varies from fresh to saline, pure to polluted, or oxygenated to anoxic, determining its utility.

The act of engineering alters the form of water by relocating, modifying or controlling it. The goal of engineering is to solve problems: water scarcity, water pollution, flooding, landslides, degradation of aquatic ecologies, etc. When freshwater is not sufficient to support a population, rivers are dammed to create storage reservoirs, water is transferred from another water basin, purified from seawater or recycled from sewage.

When there is abundant rain, we divert water and prevent soil infiltration to avoid floods and landslides. Norms of engineering dictate peeling away layers of context and circumstances to reveal an underlying form neatly explained by mathematics and physics. Then, clear boundaries define the specific scope of the problem that can be resolved.2 However, by drawing boundaries and through mathematical abstractions, these solutions overlook the embeddedness of water. Although this process seems scientific and objective, every diversion and every alteration of these water forms result in the displacement of water in another time or space, affecting communities and landscapes everywhere.

The politics of engineering shapes water quality, access and distribution, but also is latent with potential for more equitable societies. How can we engineer just water futures? If the science of engineering is based on abstractions to solve problems, we must envision new processes of asking questions. By embracing the embeddedness of water, every act of hydro-engineering asks how we can build new hydro-relationships instead of boundary objects. Rather than seeking a universal underlying form, hydro-engineering revels in working with situated knowledges and practices to nurture plural futures. The transformation of water forms shifts from the logics of extraction to generating a new rationale of sharing for a better future.

Puri | Juan Francisco Salazar

Puri is the Ckunza word for water for the Lickan Antai/Atacameño Indigenous peoples who have inhabited the Atacama Desert in northern Chile for at least ten thousand years. Lickan Antai/Atacameño peoples have always created intimate ways of communicating with puri. Often referred to as the driest place on Earth, some parts of the Atacama Desert — especially in the plateaus between the Pacific Ocean and the Cordillera de Los Andes — have not registered rainfall for centuries. In the Salar de Atacama (Atacama salt flat) rainfall in the puna (arid high-altitude plateau) allows water to flow to the basin feeding desert lagoons and giving life to extraordinary biodiversity. Puri is a most urgent and profound word in a language that is not extinct but dormant and in the process of revitalisation across many Lickan Antai/Atacameño communities. Water flows from its sources deep in the high peaks of the cerros tutelares (the guardian hills), the mountains and volcanoes that represent the abuelos (the ancestors) and sacred nature spiritualities that provide fertility, abundance, water and health. Each Lickan Antai/Atacameño community has a guardian mountain or volcano.

Ancestral practices of sowing water through thousand-year-old irrigation canals are still very much in use today for agriculture and herding just as they have been used for thousands of years. The water cycle from the high mountains of the puna to the basin of the salt flat is a cornerstone of the Lickan Antai/Atacameño cosmovision. The Bofedales are high-altitude wetlands and aquatic ecosystems located more than three thousand meters above sea level in the Andean Altiplano-Puna plateau that include springs, meadows, peatlands, saline lakes and salt flats.1 They play a critical role in the water cycle in the Andes, where today multiple human and climatic factors threaten the conservation of these altitude peat-forming wetlands, including accelerating climate change and the slow violence of brutal levels of water extraction for industrial activities.

Puri is the spirit of water connecting earth and sky. Puri is alive, it has memory and is sentient. People sing to it in the Talatur, a ceremonial chant sung during the limpia de canales across many Atacameño communities in spring (September-October). The limpia ceremony is a practice of communality where the Talatur is sung to propitiate clouds, thunder and rain, and to concentrate rainfalls where it is most needed.

Juan Francisco Salazar, LitioBillboard. 2022. Courtesy of the Author.

Wai | Dominic Leong

ʻŌLELO HAWAIʻI (HAWAIIAN LANGUAGE)

Wai is fresh water. In Hawaiian thought, wai is more than a physical substance; it is a symbol of abundance, sustenance and collective responsibility. As Mary Kawena Pukui notes in Native Planters in Old Hawaiʻi – Their Life, Lore and Environment, “Water, which gave life to food plants as well as to all vegetation, symbolised bounty for the Hawaiian gardener for it irrigated his staff of life – taro. Therefore, the word for water reduplicated meant wealth in general, for a land or a people that had abundant water was wealthy.”1

The word waiwai (literally “water-water”) extends this meaning, denoting wealth, prosperity and abundance. However, unlike Western concepts of private property, wai was never possessed. It was a shared resource, bound to collective stewardship. “Water, then, like sunlight, as a source of life to land and man, was the possession of no man, even the aliʻi nui or moʻi. The right to use it depended entirely upon the use of it,”2 Pukui explains. In this system, access to water was earned through active cultivation and sustained labour. To neglect one’s responsibility to the land and water was to forfeit one’s right to its use.

This principle extended to governance. The Hawaiian word for law, kanawai, translates to “belonging to the waters,” reinforcing the idea that laws were derived from the collective agreements over water use and distribution. “With farms along the water system upon which all depended, a farmer took as much as he required and then closed the inlet so that the next farmer could get his share of water – and so it went until all had water they needed. This became a fixed thing, the taking of one’s share and looking after his neighbour’s rights as well, without greed or selfishness.”3 As we navigate the climate crisis, the wisdom embedded in wai challenges dominant models of ownership and commodification. It suggests an alternative framework in which water is not an asset but a relational medium that ties communities together in mutual dependence with each other and our ecologies. The Hawaiian proverb “I ka wā ma mua, ka wā ma hope” reminds us that “the future is found in the past.” By honoring Native intelligence and ancestral wisdom, we can reclaim ways of living that are deeply rooted in reciprocity and care. As the climate crisis exacerbates water scarcity, revisiting kanawai offers a vital perspective: our planetary well-being lies in our shared responsibility to water. To hold wai is to hold life itself — in reciprocity with land, people and future generations.

Dominic Leong, Mālama ʻĀina, 2024. Courtesy of the Author.

Wata* | Elvira Dyangani Ose

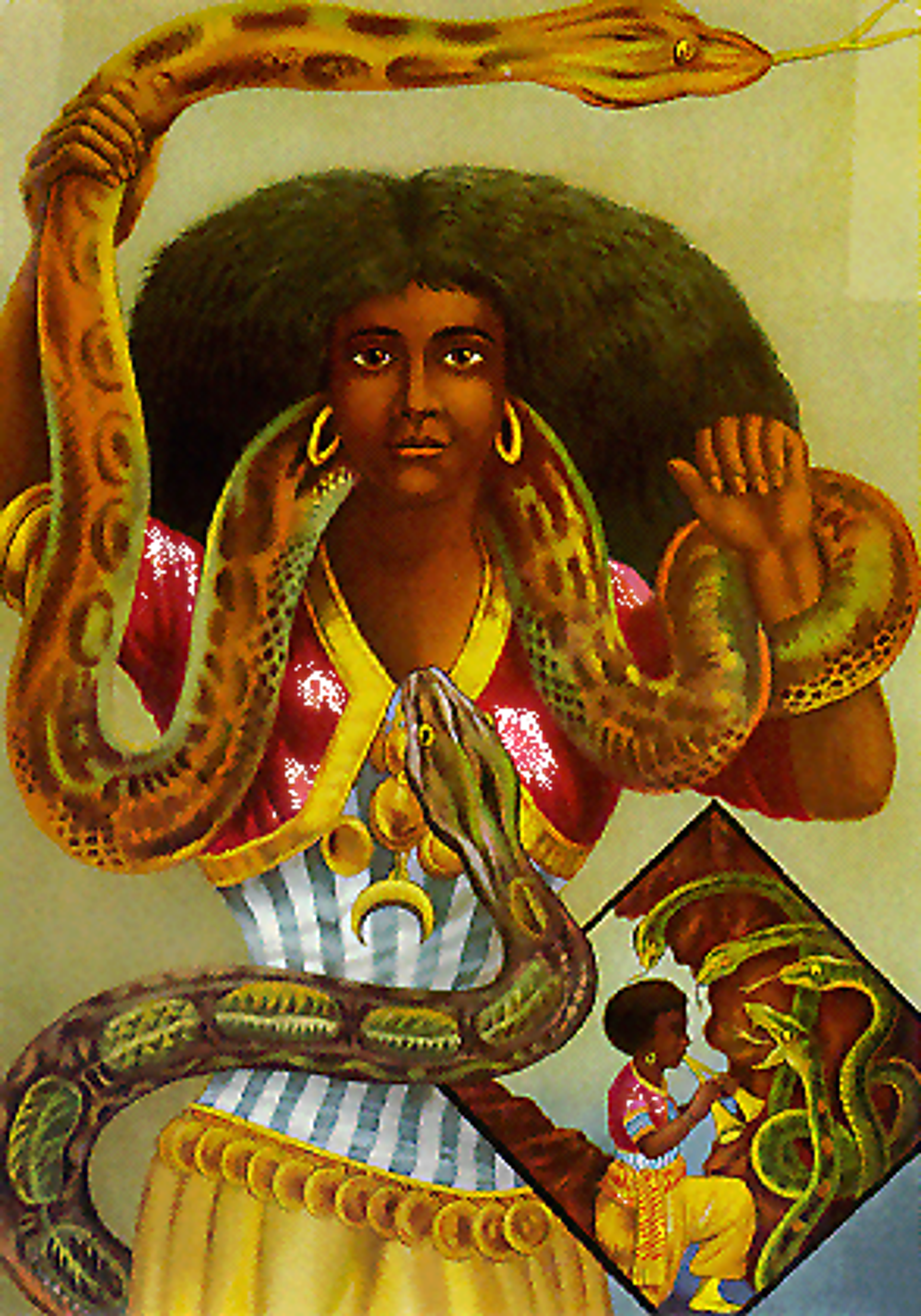

A spiritual being typical of epicontinental waters (lotic, lentic, and marine). Typical of African ancestral imaginaries and their diaspora. Its mythological origin is found in western Central African cultures (such as the Igbo where it is also known under the name of local goddesses such as Ogbuide or Uhammiri). Although frequently represented as an entity that is half cisgender woman, half aquatic vertebrate, the truth is that the less widespread popular representation of Mami Wata transcends binary conceptions of gender. Colonised narratives in the diaspora and Western mythologies feminise them — mainly after the arrival of the Catholic religion with colonisation between the fifteenth and twentieth centuries — turning them into equivalents of nymphs and mermaids. [Note: I cannot help but think here of the curiosity that the Circassian beauties of P.T. Barnum provoked in many Westerners, historically and in the present, or of the role played by Sara Baartman, the infamously called Hottentot Venus, in the imagination of the femme fatale.]1

Different cosmologies conceive Mami Wata as the generator of everything on earth, of the maternal and fertility, of women and the feminine. She is the executor of order and chaos that permeates through all planes of existence: those in which we live as humans and in others in which we are, who knows whether quantum matter, pure entelechy or the energy of an animistic object. In her physical representation, Mami Wata is a sexualised, voluptuous and seductive image, holding an intimidating snake that writhes docilely between her shoulders, arms and wrists. The figure is sometimes accompanied by a hand mirror, constituting another water reference. Curly hair is sometimes braided in the manner of those hairstyles that J.D.Okhai Ojeikere’s photographic taxonomy archived in the sixties. In others, it appears loose and disordered, like those of Circassian beauty, or in a perfect and vertiginous spherical contour, like the one that characterised the activists and Black Panthers, Angela Davis and Kathleen Neal Cleaver, or the portraits on the posters of the US Civil Rights struggles proclaiming: “Black is Beautiful.”

This spiritual significance of Mami Wata commands respect and reverence. Almost all experts allude to how Mami Wata has many and multiple faces, and when her representation is pluralised, it intersects with other cultures and their goddesses, incorporating, for instance, attributes characteristic of Christianity or Hinduism. Revered both in popular culture and in animist rituals of secret societies on both sides of the Atlantic, since the second half of the twentieth century, this entity has also intrigued artists, filmmakers and music stars. Their contributions have not only diversified the visions of this deity but also reappropriated its metaphorical meaning or investigated the complex connections of Mami Wata and her agency in the enunciation of everything we urgently need to claim, beyond any form of femininity, beyond the human to the more-than-human.

* Ref. Mami Wata or Mammywater, from the English pidgin.

Elvira Dyangani Ose, Mami Wata, poster. Courtesy of the Author.

Bios

Eva Franch i Gilabert is an architect, curator, educator and researcher based between Barcelona, Prague, and New York whose practice operates at the intersection of architecture, art and politics. She is the co-founder of FAST, a transdisciplinary creative platform. Franch is currently a professor at UMPRUM, the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, and a Distinguished Professor at the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts. Previously, she served as Director of the Architectural Association (AA) in London and of Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York, where she curated and led over thirty international exhibitions and public programs. Her work has been exhibited globally and engages with urgent questions around contemporary spatial production, architectural futures and collective imaginaries.

Mireia Luzáragga and Alejandro Muiño are architects and co-founders of TAKK, an architecture and research studio operating between Barcelona and New York. Their practice explores the intersection of feminism, ecology and design, with the aim of creating more equitable, sustainable and inclusive environments. Luzárraga currently is an Assistant Professor at Columbia University’s GSAPP in New York; Muiño has also held academic positions at Columbia GSAPP, and together with Luzárraga has also been Kengo Kuma’s Visiting Professor at the University of Tokyo. TAKK’s work has received international recognition, including the Design Vanguard 2024 by Architectural Record and the FAD Architecture Award 2023.

Dominic Leong (Kanaka Maoli) is a founding partner at Leong Leong, an internationally recognized architecture studio based in New York. He focuses on architecture as an aesthetic, social, and ecological practice. Dominic is also a co-founder emeritus of and current advisor to Hawai’i Nonlinear, a Honolulu-based non-profit that supports Native artists, cultural practitioners, and grassroots groups in caring for ‘Āina (Land/ That Which Feeds) and fostering innovative design practices.

Elvira Dyangani Osé is the Director of the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA). She was previously the director and chief curator at The Showroom gallery, London as well as serving as a lecturer in Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London, and a member of the Thought Council, Fondazione Prada. From 2012 to 2014, Ose was responsible for the Across the Board project, which was an interdisciplinary project in London, Accra, Douala, and Lagos.

Juan Francisco Salazar is an interdisciplinary researcher, author and documentary filmmaker whose academic and creative work explore the coupled dynamics of social-ecological change and is underpinned by a collaborative ethos across the arts, science and activism. As Australian Research Council Future Fellow, his project on critical social studies of outer space continues his decade-long cultural research on Antarctica.

Dorothy Tang is a landscape architect and award-winning educator at the National University of Singapore. Her work addresses the intersections of infrastructure and everyday life, especially in communities confronting large-scale environmental change. Her research explores the histories of water, infrastructure, and urbanization in East Asia, the infrastructural landscapes of foreign investments in Southeast Asia and Africa, and the geopolitics of transnational watershed management.

Christina Varvia is an architect, researcher and academic at the Centre for Research Architecture, at Goldsmiths, University of London. She is a member of the Forensic Architecture agency since 2014 and formerly acted as its Deputy Director. Her work on airstrikes, detention, right-wing, police, and border violence has been submitted to courts and parliamentary inquiries, exhibited and awarded internationally.

Liam Young is a designer, director and BAFTA nominated producer who operates in the spaces between design, fiction and futures. His visionary films and speculative worlds are both extraordinary images of tomorrow and urgent examinations of the environmental questions facing us today. As a world-builder, he visualises the cities, spaces, and props of our imaginary futures for the film and television industry.

Notes

Words and Worlds

1 Adrian Forty, Words and Buildings: a Vocabulary of Modern Architecture, (Thames & Hudson, 2000).

Expanded Body

1 American Lung Association, “How Your Lungs Get the Job Done”, 20 July 2017, https://www.lung.org/blog/ how-your-lungs-work.

2 “USDA ERS - Food Consumption and Nutrient Intakes”, accessed 28 March 2023, https://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/ FoodConsumption/. Note: data reflects an average American consumer, it is noted that food patterns vary significantly across regions.

3 Henry D. Kahn and Kathleen Stralka, “Estimated Daily Average per Capita Water Ingestion by Child and Adult Age Categories Based on USDA’s 1994–1996 and 1998 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals”, Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 19, no. 4 (May 2009): 396–404, https://doi.org/ 10.1038/jes.2008.29.

4 Lynn Margulis and Rene Fester, eds., Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation - Speciation and Morphogenesis (Mit Press Ltd, 1991).

5 Heather Davis, ‘Molecular Intimacy’, in Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary.

6 Astrida Neimanis, Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, Paperback edition, Environmental Cultures Series (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), 86.

Hydro Engineering

1 Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha, “Wetness Is Everywhere,” Journal of Architectural Education 74, no. 1 (January 2, 2020): 139–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.2020.1

2 Louis L. Bucciarelli, Designing Engineers, (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1996), 693843.

Puri

1 Adriana Aránguiz-Acuña, Gissel Alday- Galleguillos, Daniel H. Pérez, Roberto O. Chávez, Matías Olea, Comunidad Lickan Antay de Toconao, Manuel Prieto et al., “Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of depositional environment and vegetational cover in a salt flat of the Lickan Antay Territory of Toconao, Northern Chile,” Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment (2024): 03091333241306660.

Wai

1 E. S. Craighill Handy, Elizabeth Green Handy, and Mary Kawena Pukui, Native planters in old hawaii: Their life, lore, and environment, (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1972). p. 57.

2 Ibid., p.63.

3 Ibid., p.58.

Wata

1 For the Circassian beauties, see various examples, Booklet: The Circassian Girl, Zalumma Agra, “Star of the East,” produced in 1873, and accessible at Bridgeport History Center Archives - P.T. Barnum Research Collection, http://hdl.handle.net/ 11134/110002:2330; and Sara Lewis, The Unseen Truth: When Race Changed Sight in America, (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2024). There is extensive literature on Sara Baartman’s life and the myth of the Black Venus. Here is an example: T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, Black Venus, Sexualized Savages, Primal Fears, and Primitive Narratives in French, (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999).