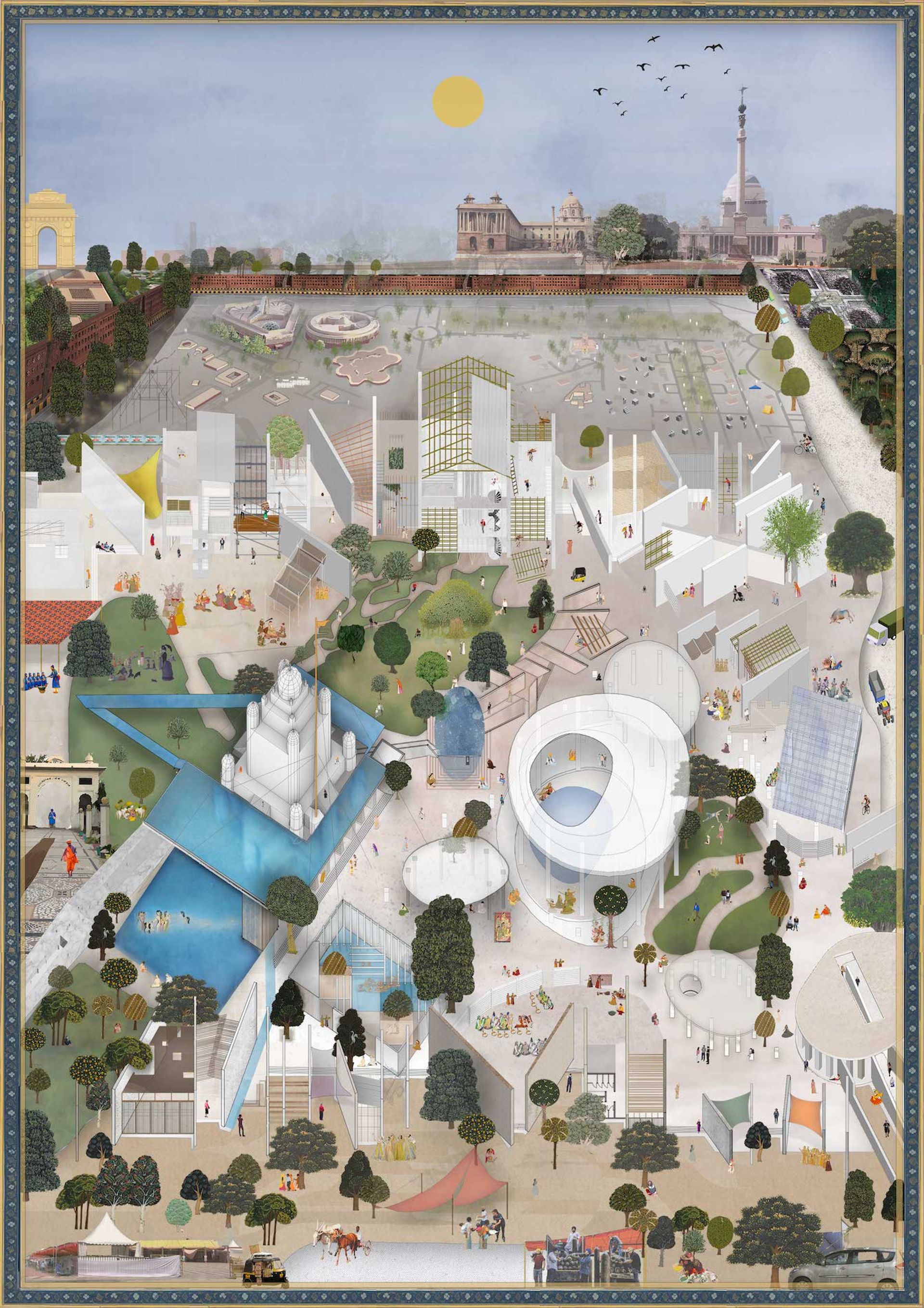

In treating the Gurudwara — a place of worship for the Sikhs — as a civic space, the civic-dwara seeks to expand the typologies and topologies of gurudwaras and civic spaces in urban environments by allowing their phenomenological and programmatic structures to be imagined, built and rebuilt over times as per requirement, in order to be perceived both as the content of their architecture and the architecture itself.

The architectural intervention reimagines the Gurudwara complex of Rakab Ganj Sahib, next to the Parliament House of India, to build a new architecture of phenomenological ideas of threshold, congregation and interface using a programmatic structure of stereotomics and tectonics, hence allowing for multiplicity in interventions and interpretations — a place for the people, one that is religious yet secular, lasting yet ephemeral, experiential yet functional.

The project was developed at the Shushant School of Art and Architecture.

KOOZ What prompted the project?

ES Civic-dwara was born out of the research, contemporary investigation of the Sikh Gurudwara, a dissertation that hypothesized that the gurudwara, the place of worship for the Sikhs, can become a civic space. Gurudwaras, unlike other religious places of worship, welcome people of all faiths through its doors. The literal translation of the word ‘gurudwara’ is the guru’s door—representing an open door for anyone who wishes to enter. Besides, this ‘open’ door, functionally, gurudwaras imbibe the three primary Sikh values of seva (service), pangat (langar: a free communal kitchen) and sangat (congregation: the act of the collective) in the many functional entities incorporated within the larger complex to benefit the larger community: schools, sarovars (pools of water), hospitals and clinics, etc.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, this altruistic nature of gurudwaras became more effective than ever as gurudwaras took upon themselves to serve the larger urban community. Starting with converting marriage or community halls into makeshift hospitals and clinics, organizing door-to- door free food services for the effected and especially, during an oxygen shortage in India, gurudwaras organized oxygen langars, free oxygen beds and tank filling stations—gurudwaras opened their doors both physically and metaphorically to everyone in need. People of all faiths and beliefs came to a religious site to serve one another.

In the coming decades, we face crises from all corners: ecological change, socio-cultural unrest, economic inequity, migration and the health crisis. Architecturally, we seem to have limited answers to most of these issues, but as the gurudwaras have shown if we pool together and serve with an open heart, we can face these crises as one—this is what prompted the project, civic- dwara.

KOOZ What questions does the project raise and which does it address?

ES The primary question the project raises is the question of collective being or conviviality as an architectural experiment. This combined with the fact that project looks at a place of worship as this civic space poses secondary concerns with regards to faith and communities in a contemporary city. With regards to its context and constructability, it raises further questions about the very nature of civic spaces in India and the larger world, we intend to build. Focusing primarily on the question of the nature of civic space, the project addresses this by proposing a system of design and building rooted both in phenomenology and programmatic eidetic of stereotomy’s and tectonics. If a room is a room, then it can be used to sleep, to rest, to enjoy a view, to eat, to cook, to congregate and to meditate, all the same time or at different times, keeping the spirit of conviviality and situated multiplicity. As Ash Amin writes in Inclusive cities:

“Public spaces are marked by multiple temporalities, ranging from the slow walk of some and the frenzied passage of others, to variations in opening and closing times, and the different temporalities of modernity, tradition, memory and transformation. Yet, on the whole, and this is what needs explaining, the pressures of temporal variety and change within public spaces do not stack up to overwhelm social action.”

The built environment of these public spaces thus must address these questions by imagining a building system of constant flux. The civic-dwara, as discussed before starts this conversation by allowing built environments to be rebuilt perpetually by proposing a system of stereotomics (walls, seating, plumbing, electric lines, etc) and a system of tectonics (roofs, enclosures, tent structures, screens and more) interlaced with thresholds, congregations, and interfaces, that are designed to allow for situated multiplicity.

KOOZ How does the project challenge the potential of space between religion and civic engagement?

ES In recent years, the aspirations of urban practitioners have veered towards the civic and the communal: urban parks, social housing, shared urban farms and more rather than political outcomes. However, as Amin states in Inclusive Cities, urban activists continue to believe that inclusive urban public spaces remain an important political space in an age of organized, representative, and increasingly centralized and also veiled politics. Such spaces – both iconic and major spaces of public gathering as well as more peripheral spaces tentatively occupied by subaltern groups and minorities – are seen as the ground of participatory politics, popular claim and counter-claim, public commentary and deliberation, opportunity for under-represented or emergent communities, and the politics of spontaneity and agonistic interaction among an empowered citizenry. Here, the social dynamics of public space are judged as the measure of participatory politics.

Keeping that in mind, the project in question, the civic-dwara picks on these aspects by analyzing the gurudwara, a shared common among the people of the Sikh faith, who open their door and hearth to whoever wishes to enter. In a gurudwara, a minority community, in most settings, creates a forum for empowered citizenry by encouraging and preaching the act of seva, or service to all. Public gathering is not seen as an act of faith but a call to action in most scenarios, as the community comes together to feed the poor, encourage vaccination, create blood banks and much more. The potential for civic engagement is primarily rooted in the making of the gurudwara itself which stands on the principle of open doors and open hearts. Constructing a religious institution which can keep its ritualistic running intact while interlacing the more public functions to run independently or interdependently, is the challenge that the civic-dwara steps up to.

The potential for civic engagement is primarily rooted in the making of the gurudwara itself which stands on the principle of open doors and open hearts.

KOOZ What is the value of civic space in the contemporary city?

ES Only three percent of the world’s population lives in countries with open civic spaces, according to CIVICUS Monitor, a global research collaboration which rates and tracks respect for fundamental freedoms. This statistic leads to an argument that civic space in the contemporary city is perhaps a luxury and not an assumed reality. Thus establishing the fact that any functioning civic space in existence in a city is a valuable entity simply because of its rarity. Urban public space has become one component, arguably of secondary importance, in a variegated field of civic and political formation.

One may follow Jane Jacobs (1961) and in more recent years Richard Sennett (2006), to trace the «virtues» of urban surplus to public spaces that are open, crowded, diverse, incomplete, improvised, and disorderly or lightly regulated. These virtues, as argued by them, are not merely improvements to human life, encouraging interaction, social culture and democracy but are essential to the “human” way of life. As Lincoln put it, humans are social animals. Beyond home and work, where would a human socialize, talk, interact, relax, read a book…?

The civic-dwara draws on comes from a long lineage of thought including the classical Greek philosophers, theorists of urban modernity such as Benjamin, Simmel, Mumford, Lefebvre and Jacobs, and contemporary urban visionaries such as Sennett, Sandercock and Zukin, all suggesting a strong link between urban public space and urban civic virtue and citizenship. If these values are put to practice public space, if organized properly, offers the potential for social communion by allowing us to lift our gaze from the daily grind, and as a result, increase our disposition towards the other.

KOOZ How and to what extent has the current pandemic informed and affected the way we design and inhabit/explore this?

ES The current pandemic has been instrumental in developing and shaping our realities today. The guidelines as proposed by health experts do not allow us to associate civic or public spaces with tightly-packed stadiums, closed quarters or rubbing shoulders. This new reality has also shown us the lack of adaptability in our public spaces and how they must be able to address concerns of public importance more immediately — be it health or socio-economy. The way we design or in fact the way we see the world must become attuned to the future we hope to realize.

The civic-dwara started out as a socio-cultural question but the pandemic has shaped its being into one of multiplicity in function. Around the peak of the pandemic, stadiums or banquet venues turned into makeshift hospitals and clinics. This “makeshift” architecture could be considered as the paradigm shift in the manner which we build. Large construction projects cannot solely be looked at for their economic benefits, they need to be multi-functional while keeping in mind the environmental and social impact they would have on the larger city.

KOOZ What is the power of the architectural imagination?

ES Architectural discourse often revolves around two words, what if. The architect is inevitably a practitioner or thinker of the proposed or the imagined. Imagination, if considered through Kantian epistemology, bridges the gap between perception and understanding, the sensuous experience of phenomena and the work of conceptual thought. It demarcates a cognitive space where, in Paul Guyer’s words, “architecture is thought of as expressing and communicating abstract ideas, not just aiming for beauty and utility.”

This epistemological view of architectural imagination enables one to appreciate any sketch, drawing or render as not just a representative medium or a bridge between artistic vision and scientific/logical reason to build, but as knowledge itself. It enables discourse beyond aesthetic and function, it encourages critical thinking, it embodies values and principles, it is culture and enables cultural activity, and it enables life itself.

Bio

Ekam Singh Sahni is an architect and writer, based in New York City. He is an M.Arch. candidate at the Pratt Institute and a B.Arch. graduate (gold medallist; from Sushant School of Art and Architecture). He has worked on various international design-builds involving the refugee crisis, adaptive-use architecture and prefabricated housing. With a penchant for the written word, he is interested in exploring architecture that informs our collective well being. His work has been published on platforms such as LiveWire and Rethinking the Future.