November 23, 2023 marked the inauguration of the Computational Compost project at the Tabakalera centre in Donostia-San Sebastián, addressing the environmental impact of data storage. In collaboration with the Donostia International Physics Center — where the world's sixth quantum supercomputer, IBM Quantum System One, will be located — the project also includes a film directed by Locument and Marina Otero Verzier. In this interview we learn more about the potential synergies between technology and ecology.

KOOZ The exhibition Computational Compost presents a prototype which uses the heat emitted by computers running simulations of the origin of the universe to power a vermicomposting machine. The prototype is part of a number of alternative models which are being tested to redirect the by-products, in this case heat energy, of our digital landscape. How does the decomposition occurring in the compost serve as a reminder of the fragility of these gargantuan digital infrastructures?

MARINA OTEROThe Computational Compost prototype addresses the environmental impact of data production and storage. It is a possible application for the Donostia International Physics Center (DIPC), which currently redirects the heat generated by its supercomputers into its immediate environment. This process has caused, for example, a nearby loquat tree to bloom prematurely. Understood on a planetary scale, this particular case reveals deeper dimensions, highlighting the significant impact that digital infrastructures can have on processes related to climate change.

Fragmentation is essential for both computing and composting, facilitating metamorphosis and the generation of new realities. The prototype proposes a synergy between technology and ecology. Through metabolic processes, it links computational energy, deployed for deciphering the mysteries of the origin of life, with the earthly processes that perpetually regenerate it. Digital galaxies unfold on a Raspberry Pi farm, executing simulations of the origin and expansion of the universe developed by the scientists at DIPC. The heat emanated from these simulated cosmos feeds a vermicomposting machine where the byproducts of digital processes and organic waste are transformed into fertile soil by living organisms.

"Computational Compost provides an a-human reading to our obsession with data: if we continue living as we do, our bodies and territories will disappear, and our data will become raw material for microorganisms, worms, and artificial intelligences."

- Marina Otero Verzier.

The prototype brings attention to how celestial and biological bodies are linked by processes of decomposition and regeneration that weave cosmic, computational, and earthly scales and times, displacing humans from their traditional centrality. Yet, the prototype should not be understood as a fixer. Our focus is not solely on making data centres more efficient and eco-friendly. That effort is in vain if not done alongside reconsidering the ethics of a society founded on extractivism and consumerism. We need to shift our relationship with data and embrace other forms of living, because our compulsion to create new digital worlds destroys this imperfect world we inhabit.

In fact, Computational Compost also provides an a-human reading (referring to the work of Patricia MacCormack) to our obsession with data: if we continue living as we do, our bodies and territories will disappear, and our data will become raw material for microorganisms, worms, and artificial intelligences.

Computational Compost, project by Marina Otero Verzier. Photo Claudia Paredes.

KOOZ Most new models being developed today assume the inevitability of an ever-increasing data production. Instead of aspiring to a storage medium that allows unlimited accumulation, you advocate for a practice that recognises our dependence on data and accompanies us in processes of detachment, loss, mourning for digital, individual and collective data. To what extent can public institutions — such as museums, archives, libraries — help us in conceiving alternative models?

MO Institutions, in my view, are public forums and political spaces for testing new models. For instance, Computational Compost is inspired by research on data centre models in Sweden, particularly my December 2022 visit to the Infrastructure and Cloud Research & Test Environment (ICE) Data Center in Luleå. ICE tests innovative prototypes, such as using mealworms — themselves grown from the heat of server cooling systems — as chicken feed, instead of the environmentally destructive soy concentrate grown in the cleared forests of the Amazon. The chickens are quite happy with their new diet. However, I wanted the worms to be happy too, so in our prototype, they don’t become feed. Instead, the worms will enjoy a second life outside the museum, in a nearby garden where — who knows — they might also end up inside a chicken!

"If we reach a point where we simply can't save anymore, which parts of our immense digital archives should be preserved for future generations?"

- Marina Otero Verzier.

Similarly, Tabakalera is devoted to artistic and sociocultural experimentation, hosting collaborations between artists and scientists. Here, exhibitions are not endpoints but sites for collective research and action towards alternative ways of living. For this particular project, Tabakalera invited us to develop a prototype together with DIPC addressing the impact of data production and storage. We focused on both the ecological impact of digital infrastructures and our compulsion to store ever-growing volumes of data, even in the face of climate catastrophe. Humans and artificial intelligences are amassing data at a rate that will soon surpass our storage and processing capabilities. This situation also affects institutions such as museums, archives, and libraries that are in the business of collecting information and constructing institutional, collective memory. If we reach a point where we simply can't save anymore, which parts of our immense digital archives should be preserved for future generations? Who will be able to save, and who won’t? Currently, corporations predominantly control this, often prioritising profit over ecological and social concerns, leading to significant environmental damage and a loss of sovereignty over our knowledge and memories, transformed into datasets that are amassed as capital.

"What Computational Compost emphasises is that collective memory is not limited to that which is stored in a server or an archive. It is a dynamic practice, involving acts of remembering and forgetting; the generation of knowledge, and its loss."

- Marina Otero Verzier.

What Computational Compost emphasises is that collective memory is not limited to that which is stored in a server or an archive. It is a dynamic practice, involving acts of remembering and forgetting; the generation of knowledge, and its loss. Archivists understand that digital files, like physical records, undergo states of proliferation and decay. Digital documents are continuously renewed through maintenance practices, software and hardware updates, and new interpretations that update their meanings. That’s why I advocate for producing and storing less data and for designing collective processes to decide what to preserve and what to let go. I'm interested in merging the fields of preservation and digital infrastructure to envision an ecological, political, and social practice of deletion and mourning. Just as we mourn objects, places, and people, letting go of data requires a grieving process that recognises the emotional burden of parting with those digital fragments of ourselves. We must also demand accountability and action from multinationals and digital platforms, which have aggregated these fragments into databases mined by algorithms and stored in media designed to endure long after we become compost.

KOOZ Across from the vermicomposting machine, the video developed in collaboration with Locument is focused on the research you have been undertaking on the quipu, a coding system at the base of the Inca empire whose mathematical organisation anticipates the operations of a computer. What drew you to the quipu and the territory of Chile?

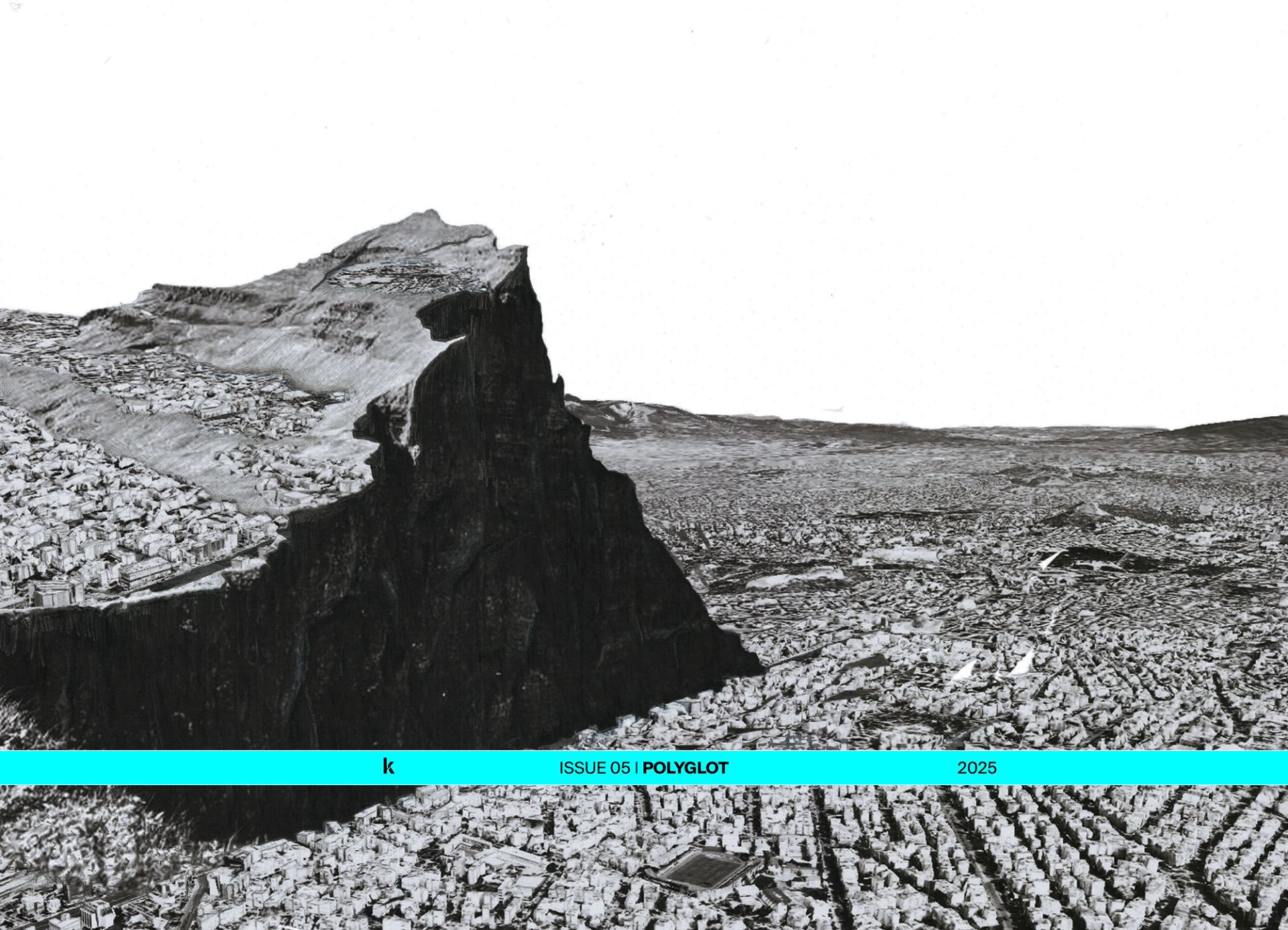

MO I had visited Chile before, during the research conducted for the book Lithium: States of Exhaustion, co-edited with Anastasia Kubrak and Francisco Diaz. Recently, the research I am conducting with the support of Harvard’s Wheelwright Prize took me back to that country. Its system of fibre-optic cables (such as the existing Google and Curie cables, as well as the upcoming Humboldt), numerous data centres, supercomputers, and data-intensive industries like astronomical observatories, would position Chile not only as a hub for digital communication but also as a battleground against extractivist economies. Connectivity, coupled with governmental support, attracts tech giants like Google and Microsoft to establish their presence here, bringing prospects of socio-technical advancement for Latin America.

However, these developments come with environmental and social tolls, marked by substantial CO2 emissions and a continuous need for energy and water to cool their facilities. In Santiago, for example, the Movimiento Socioambiental de Cerrillos por el Agua y el Territorio (Mosacat) successfully resisted a Google data centre megaproject by voicing concerns over its overuse of Santiago's central aquifer, particularly given the region's drought. Inhabitants in Quilicura, Santiago, are denouncing the threatening effects of data centres on the local wetland ecosystem. I was interested in learning more and contributing to these struggles. Yet, in addition to data centres, I am also interested in other mediums for storing information, which is how, during a visit to the Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino in Santiago, I learned about the quipus I was immediately fascinated by their beauty and sophistication, which led me to read more about their history and design.

"Granting certain legitimacy to quipus, however, was part of a strategy aimed at establishing “order” in the Andes to optimise the extraction of resources."

- Marina Otero Verzier.

KOOZ Spanish colonisers imposed Hispanic writing over the quipu string system and, in the absence of written Inca records, the empire’s history has been principally written by the Spanish colonisers. Despite the fact that contemporary computers and data centres encode and process immense amounts of information, quipus are still indecipherable. How would the reading of these coding systems transform our understanding of the Inca empire and its social organisation?

MO As you say, in the early stages of colonisation, Hispanic writing was prioritised over the quipus' system of strings, which was mostly illegible to the colonisers. Later, around the 1570s, the quipus were incorporated into administrative contexts as part of a strategy to consolidate colonial power. Granting certain legitimacy to quipus, however, was part of a strategy aimed at establishing “order” in the Andes to optimise the extraction of resources. It entailed the forced relocation of Andean populations to Hispanic-style settlements and the establishment of a system of municipal councils, where scribes would transcribe the quipus kept by each community, containing their information and histories. Still, during that time, quipus were used in everyday resistance practices against colonial rule, as they facilitated the planning of uprisings through knotted messages illegible to colonial officials.

These episodes triggered what has been described as the colonisers' “fear of the knotted rope,” which finally led to the prohibition of the quipu by the Catholic Church in 1583. Not many survived. And despite the occasional transcription of accounting quipus by the colonial administration, their records were not kept together with the quipus or their illustrations. As a result, the relationship between the quipus and their meanings is now mostly unreadable. Inca “history", as recounted by Europeans in colonial texts, reflects the language barriers and differing worldviews they encountered, leading to contradictions and, in many cases, intentional fabrications for the purpose of legitimising conquest or evangelisation.

"Today's digital infrastructures are seen as a key to unlocking the secrets of the quipus and advancing knowledge of the Inca Empire. Many researchers are using AI in their efforts to decipher quipus."

- Marina Otero Verzier.

Today's digital infrastructures are seen as a key to unlocking the secrets of the quipus and advancing knowledge of the Inca Empire. Many researchers are using AI in their efforts to decipher quipus. There are more than 850 digitised quipus around the world, and they have been transformed into de facto databases mined by computer algorithms in search of large-scale patterns.

KOOZ Let’s assume that current computers could uncover the secrets embedded in the more than 850 quipus which have been digitised around the world. Are these secrets ours to unveil?

MO I'd argue that the desire to unravel the mysteries of the Andean past, as embodied in the quipu's cords, is part of the same logic that endangered the landscapes and communities from which quipus originated. Academic and scientific efforts to collect, digitise, and decode quipus tie back to the European colonial order and the extensive material, cultural, and epistemological destruction it caused. Transforming quipus into digital assets and Cartesian databases subjects indigenous knowledge and cosmovision to Western knowledge once more. The knots in quipus connect the bodies, ecosystems, and knowledge erased by colonialism with those threatened today by our relentless use of resources. Instead of attempting to mine and extract every bit of the quipus' information, perhaps we should accept their inscrutability as a way to push back against the totalising Western European gaze and the compulsion for more. By mourning the surviving cords as evidence of the destructive force of colonialism, we recognize that what was really lost, what was destroyed, was the embodied knowledge to create and interpret quipus and the entire network of social, cultural, and environmental relations organised around them.

"Instead of attempting to mine and extract every bit of the quipus' information, perhaps we should accept their inscrutability as a way to push back against the totalising Western European gaze."

- Marina Otero Verzier.

Four centuries after their prohibition, and despite being indecipherable, Quipus still have a history to tell. As our bodies and worlds disappear, our countless digital files will face the same fate as those ecosystems and social structures affected by their processing and storage.

KOOZ The quipu is testament to how, throughout history, empires have depended on communication networks. At a time when the management of our data is in the hands of big private corporations, what is the potential of rethinking data as a good which is run by self-organised communities? To what extent could this counterbalance enormous ecological and social scars that the digital industry is bearing on Chile’s landscape and communities?

MO I believe in the importance of community mobilisation. During my last visit to Santiago, representatives from the Quilicura community asked me and my research partner in Santiago, Nicolás Díaz, to support them in their demands for a more ecological approach to the functioning of data centres in the region. That's how we, together with Serena Dambrosio, organised a hybrid forum, with the purpose of establishing a collaborative methodology among government representatives, municipal entities, the private sector, academic institutions, and local communities. This forum, taking place in mid-January 2024, seeks to combine efforts and knowledge towards new prototypes for data centre governance and design, prioritising the reduction of resource consumption such as energy and water, and the consultation with local communities.

"I aim for a cooperative model, a sort of collectivisation of digital infrastructure. The case of Quilicura will be the starting point."

- Marina Otero Verzier.

I aim for a cooperative model, a sort of collectivisation of digital infrastructure. The case of Quilicura will be the starting point. This was possible thanks to Quilicura's community vision and efforts, the support from the Wheelwright Prize, the CCA's Architecture as Public Concern Fellowship 2023, and Núcleo Milenio (FAIR) "Future of Artificial Intelligence Research," and will include participants such as Kate Crawford, Jaime San Martín, Martin Tironi, and Rodrigo Vallejos. We are very excited about the possible outcomes of this forum. Hopefully, one of them will be a pilot project for a decentralised network that can be managed at the neighbourhood level.

KOOZ Only by being aware of these processes and dynamics can we as citizens speak up and stand up to those who have a seat at the policy making table/s. Locument team, what is the potential of using film as a critical and subversive tool to unfold such complex and multilayered researches?

LOCUMENT One of the aspects crucial to our kind of filmmaking is physical presence: the fact that we, as creators, immerse ourselves in the distinct contexts that constitute the movie. Inevitably, this methodology is determinant in defining each project's content and format. It is in this process that the intangible is captured and, by being transposed into this medium, becomes palpable.

As film requires us to create narrative, it gives the opportunity to interpret our surroundings. With research as a base, audiovisual representation creates a starting point for debate. It is here that we see movies as mediators, as presenters of distinct points of view and formulators of questions for the audience to reinterpret their understanding of the world.

"We see movies as mediators, as presenters of distinct points of view and formulators of questions for the audience to reinterpret their understanding of the world."

- Locument.

In Computational Compost, the film takes Marina Otero’s research as a base for its narrative, following the thread of the real-world impacts of data storage and the digital infrastructure; in parallel, the visual simulations provided by DIPC present the knowledge frontier accessed only via supercomputers and complex processing power. We position the viewer somewhere in between these two opposite coordinates of the same vector, aiming to create a comprehensive representation of the problematics of data futures.

Computational Compost has the purpose of revealing how data centres and digital infrastructure, so often made invisible to the common user, have the most real implications of our physical world. As phrased in the film “The Cloud does not float above the ground; it is built into its depths.” It is here that the Quipu embodies an important literal metaphor, as a functional object devoid of its function, it stands to represent both its own history as well as a symbolic comparative of a contemporary equivalent, reminding us of the human need and desire for data storage, as well as confronting what might happen when this data is lost.

"The ultimate goal is to develop a vocabulary that enables the spectator to unfold the layers that comprise the world we inhabit and take part in the discussion that can generate changes in their own context."

- Locument.

We embrace the impossibility of a film to be impartial or objective; rather, we attempt to incorporate a multitude of perspectives and contexts so that viewers can create their own narratives and conclusions, stimulating discussion rather than providing definitive answers. While there is a need to create a narrative and to communicate its complexity, the ultimate goal is to develop a vocabulary that enables the spectator to unfold the layers that comprise the world we inhabit and take part in the discussion that can generate changes in their own context.

Credits

Artistic Direction and Research: Marina Otero Verzier

Project Coordination and Research: Claudia Paredes Intriago

Film Direction: Locument (Francisco Lobo, Romea Muryń); Marina Otero Verzier

Collaborators: Pablo Saiz del Río, Fernando Fernandez Sanchez, Gaspar Cohen, César Arenas, Rocco Roncuzzi, Jacinto Moros Montanes, Xabier Abel Martinez, Diego Cabezas.

In partnership with the Donostia International Physics Center (Txomin Romero, Silvia Bonoli, Raul Angulo, Jens Stücker).

Computational Compost is part of the exhibition Máquinas de ingenio. Jakintzen bidegurutzean curated by Maria Ptqk at Tabakalera, which can be visited until February 4, 2024, at the Tabakalera Contemporary Culture Center, Donostia-San Sebastián.

Bio

Dr. Marina Otero Verzier is an architect, researcher, and visiting professor at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation at Columbia University, New York. Since 2023, she has been a member of the Advisory Committee for Architecture and Design at the Reina Sofía National Museum and Art Center. Otero Verzier specializes in the relationships between architecture and digital infrastructures and resources such as lithium that sustain them. In 2022, she received the Harvard Wheelwright Prize for a project on the future of data storage. Between 2020 and 2023, she was the Director of the Master in Social Design at the Design Academy Eindhoven, and from 2015 to 2022, Director of Research at Het Nieuwe Instituut, where she led initiatives focused on labor, extraction, and mental health. Previously, she was Director of Programming for the Global Studio-X Network, Columbia GSAPP. Otero Verzier has curated exhibitions such as ‘Compulsive Desires: On the Extraction of Lithium and Rebellious Mountains’ at the Municipal Gallery of Porto in 2023, ‘Work, Body, Leisure,’ the Dutch Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2018, and ‘After Belonging,’ the Oslo Architecture Triennale in 2016. She has co-edited “Automated Landscapes” (2023), “Lithium: States of Exhaustion” (2021), “A Matter of Data” (2021), “More-than-Human” (2020), “Architecture of Appropriation” (2019), “Work, Body, Leisure” (2018), and “After Belonging” (2016), among others. Otero Verzier studied at TU Delft and ETSA Madrid and Columbia GSAPP. In 2016, she received her Ph.D. from ETSA Madrid.

Locument is a research studio founded in 2015 by Francisco Lobo and Romea Muryń that combines filmmaking with architecture and urban research. They use architecture and film as analytical, critical and subversive tools to emphasise contemporary issues and dissect their resolutions. They see the importance of observing rapidly changing social conditions through the influential factors of technology, economy, politics and urban environment. Locument’s movies have been screened internationally at exhibitions and film festivals such as – the 15th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, the 18th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, Italy; the 25th Biennial of Design Ljubljana, Slovenia; Arquiteturas Film Festival, Portugal; Archstoyanie Festival Festival at the Nikola-Lenivets Art Park, Russia; In-Between Conditions Media Art Festival Tbilisi, Georgia; Commiserate Chicago Media Art Festival, US. They have collaborated with institutions such as MIT Architecture Department, INDA - Chulalongkorn University Faculty of Architecture, Nikola-Lenivets Classroom, OSSA - Polish Association of Architecture Students.

Federica Zambeletti is the founder and managing director of KoozArch. She is an architect, researcher and digital curator whose interests lie at the intersection between art, architecture and regenerative practices. In 2015 Federica founded KoozArch with the ambition of creating a space where to research, explore and discuss architecture beyond the limits of its built form. Parallel to her work at KoozArch, Federica is Architect at the architecture studio UNA and researcher at the non-profit agency for change UNLESS where she is project manager of the research "Antarctic Resolution". Federica is an Architectural Association School of Architecture in London alumni.