The talk below and subsequent discussion have been edited and excerpted from the session symposium ‘Startup Architecture: Venture as a New Mode of Practice’, held at ETH Zurich on 17 September 2025, with the kind permission of the organisers; more information can be found here.

A Patent Atlantis, Professor Silke Langenberg *

Even though not every startup begins with a patent, I believe — and I know from experience — that patents can play a crucial role in the transition from an invention to the foundation of a business.

Within our ongoing research project on Architecture and Patents, supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, we have been examining the role of the patent as an actor or driver of innovation in architecture. Although the 21st century is still young, it already presents an impressive range of new materials, construction techniques, and building processes. Yet none of these would be possible without the creativity and innovation of earlier generations of engineers and architects.

"Although the 21st century is still young, it already presents an impressive range of new materials, construction techniques, and building processes."

Since the late 19th century, patents have played a key role in protecting inventions and helping inventors or companies secure a strong position in the market. Over the past two decades, globalisation and digitalisation have led to a sharp rise in patents within the construction industry. One reason is that more architects are filing patents to protect their designs from imitation. Another is the rise of digital fabrication, where new developments often build on earlier inventions.

Digital fabrication allows us to rethink old ideas — and some patents created during times of crisis or scarcity might even help us address today’s challenges, such as climate change and resource shortages. Revisiting historical patents — both famous and forgotten — feels more relevant, timely, and inspiring than ever. Under changing circumstances, they can reveal unexpected potential or inspire entirely new ideas and even new businesses.

Let’s look at an example from the early 20th century: the invention of building materials made from waste products. Builders began experimenting with stones made from slag and ashes — an early step toward what we now call sustainable construction and materiality. The hydraulic properties of blast furnace slag and, to a lesser extent, regular slag and fly ash were discovered in the late 19th century. But it was only after World War I, during a period of economic hardship, that slag gained renewed attention across Europe.

Coal was scarce, energy was expensive, and traditional bricks were costly to produce. Slag bricks — artificial stones made from slag and ash — offered a promising alternative. Easy to produce, requiring less energy, and making use of waste materials that would otherwise need large disposal sites, these lightweight stones represented an early example of sustainable thinking in construction.

Patent holders in this field quickly diversified their strategies. They filed patents covering every stage of the production process — from the mixtures used to make the stones, to the machines that mixed, pressed, and cured them. Patents addressed every aspect of cost reduction, efficiency, and early automation; the fees and licenses these patents generated became important business drivers.

"Revisiting historical patents — both famous and forgotten — feels more relevant, timely, and inspiring than ever."

Before digitalisation enabled mass production of customised components, simplifying and standardising building elements was essential for industrial production. This need drove the development of system buildings in the 1930s and especially during the 1960s, when Europe faced a severe housing shortage after World War II. Large-scale housing projects began to use solid precast slab systems. These standardised elements were prefabricated either on site or in nearby factories.

One pioneer in this field was IGÉCO AG, founded in 1956. The company became a leading force in Switzerland's industrial construction sector, building residential complexes using prefabricated concrete elements. To prefabricate the large concrete elements, IGÉCO developed its own vibrating tables with timber and steel molds and filed a patent for Dispositif pour le moulage orbital in 1963. A year later, the company patented special metal plate anchors that allowed panels to support themselves without grouting. With its patents and licenses, IGÉCO held a significant share of the Swiss market, and was responsible for thousands of apartments during the 1960s and 70s.

Similar developments took place across Europe, particularly in Germany and France, where the reconstruction needs were even greater. Standardising buildings and reducing the number of construction elements became key to the industrialisation of the building sector in the second half of the 20th century. Concrete became the dominant material — cheaper than steel and well-suited to prefabrication. In Germany, for instance, the number of concrete prefabrication companies grew from just 14 to over 500 in only three years.

At the same time, new static and mechanical formwork systems were developed for high-rise construction — such as climbing and sliding formwork. These systems evolved from technologies originally used in silo construction at the turn of the century. The first patent for slip casting, for example, was filed in 1900 by the engineer Charles Hagelin, while the influence of American industrial and silo architecture on European construction industrialisation was vividly described by Reyner Banham in A Concrete Atlantis (1986).

So, can patents support the startup process? My answer is: yes and no. Applying for a patent requires significant investment — of time, money, and expertise. But if successful, it can offer valuable returns. To conclude, I’ll return to the ETH Machine Laboratory and explain why my team and I are so deeply interested in patents. For us, patents are not just technical documents — they’re also part of our construction heritage.

The buildings designed by Otto Rudolf Salvisberg for ETH, extensively renovated between 2013 and 2023, illustrate this beautifully. The most iconic space, the Machine Hall, once housed machinery for teaching and research and now serves as the home of ETH’s Center for Robotics. In 1933, the hall was fitted with a Luxfer glass-concrete ceiling — whose story is closely tied to Frank Lloyd Wright’s design patents for the Luxfer Prism Company. The earliest Luxfer patents date back to the 1890s. In Zurich, the firm Robert Loser & Co. made these glass-concrete ceilings accessible under Swiss and German patents licensed from Luxfer.

Unfortunately, the original ceiling began leaking in the 1950s and was boarded up for decades. During its recent renovation by Itten Brechbühl, architects sought to reconstruct the original ceiling. And once again, a patent made this possible: Marco Semadeni’s 2015 patent for a new glass-concrete system — three times thicker than the original — allowed the ceiling to meet Swiss building standards while restoring the hall’s historic appearance.

This example reminds us that innovation doesn’t always mean creating something entirely new. Sometimes, it’s about reinterpreting the past with new technologies. So, as you develop your own research or startup ideas, remember: the potential for innovation doesn’t lie only in new construction, but also in the existing building stock. Revisiting old patents and historic inventions can reveal unexpected and shining paths forward.

Federica Zambeletti / KoozArch We began today by talking about how architects historically became involved with patents, as a way to protect their designs. In relation to the broader urgencies of our time — both social and environmental — is the commercial model of patents and protection still the best way forward? Could more open-source, accessible, and collaborative approaches to producing architecture practically offer a more viable or interesting alternative today?

Silke Langenberg I would say yes, I agree that alternative methods can forge another path — especially when it comes to sharing knowledge and research. On the other hand, patents serve as a form of protection, particularly when starting a business. When it comes to funding, investments or money, a patent acts as a legal instrument to help securitise these. However, patents can also block innovation. They can prevent others from working with a certain technique if they can’t afford the fees, much like patents in medicine — not everyone has access. So while patents are essential for startups and running a business, they can also create barriers for broader innovation.

Regarding the protection of original designs; in German, for example, the right term would be a Gebrauchsmuster. I think that a certain distinction is quite crucial: are you trying to protect a design itself — which can be difficult with a patent — or is it a process, a new material, a construction technique, or a machine? There are really important differences here. We’ve seen a rise in patents from architects, but also in efforts to protect design ideas. This even led to discussions a few years ago with a colleague who wanted to patent floor plans for housing. That kind of thing, as you can imagine, is quite difficult to protect under patent law.

"Are you trying to protect a design itself — which can be difficult with a patent — or is it a process, a new material, a construction technique, or a machine?"

KOOZ In what ways have patents potentially filled gaps in the fields of architecture and construction? How have they positioned themselves within these areas?

SL I think the most important patents were those filed for new construction processes; I would say they were really the main driver. When a patent is combined with a large company that already builds substantial housing stock, that becomes a key driver. In that scenario, the company and the inventor can work together, or the inventor might even start running a company themselves. Facade systems are another example of something very special. They require highly specific knowledge of the process, materials, connections, and details. All of these elements come together, allowing the system to be sold as a single product, which makes it very easy for the client.

KOOZ If we accept startup culture within architecture as a term which is still in definition, what are its defining characteristics?

Gilles Retsin Maybe I can frame it like this: not every entrepreneurial venture qualifies as a startup. The key qualifier is that a startup involves technology with the explicit goal of scaling. It’s really that link to scale that matters — it’s not just any entrepreneurial adventure. A startup is about building something designed to grow significantly.

"The key qualifier is that a startup involves technology with the explicit goal of scaling."

Débora Mesa Molina I see startups as strategy. They’re a tool to build good architecture. In our case, we’re very focused on making affordable housing, as we believe that, technologically, we can create much better housing — housing that is of a higher quality, more sustainable and more cost-effective. It’s just a matter of putting the right resources, intelligence, and capital to work. If startups are the way to achieve this, then that is the way forward. If we need to approach it differently, wear a different hat, or adopt a different strategy, we will. But if we can create a trend where startups become a real vehicle to challenge and accelerate this energy, then why not pursue it?

"We believe that, technologically, we can create much better housing — housing that is of a higher quality, more sustainable and more cost-effective. It’s just a matter of putting the right resources, intelligence, and capital to work"

Jelle Feringa I think there’s also a generational shift taking place. I came to architecture in the nineties, and at that time the discipline was extremely subjective — it was almost like practicing philosophy rather than designing buildings. The generation before mine — the likes of Koolhaas and Liebeskind — was so built around personality that many of the objective aspects of architecture — engineering, technology — were largely set aside or outsourced. Architecture became purely about design and lost much of its technical foundation. Because of that, some of the authority within the profession was also eroded. I think now, in a sense, we’re trying to recover some of that lost ground.

"Architecture became purely about design and lost much of its technical foundation. Because of that, some of the authority within the profession was also eroded. I think now, in a sense, we’re trying to recover some of that lost ground"

KOOZ When we think of startups and technology, the driving objective tends to be around growth. How do you navigate this balance between scale and growth on one hand, and measuring impact on the other?

GR I think this is actually a really unique relationship, and I believe it’s one of the reasons why this model works so well. In our case — and in Débora’s case as well — we’re focused on creating large amounts of affordable housing. That’s our core goal. This approach combines societal impact with the necessity of growth and scale — because you can only achieve meaningful impact at a certain scale.

It’s actually the same with climate technology. For example, one of our investors is a climate fund that is legally bound to invest only in startups that can demonstrate measurable carbon removal from the atmosphere. For them, investing isn’t just about supporting a startup — it requires that the startup achieves a sufficient scale of impact. So for me, impact is inherently tied to growth and scale. Without it, it’s simply virtue signaling — it’s not real impact.

KOOZLet’s talk about access: you’re building mass housing for many people — generally considered a social initiative — yet we see a video of an autonomous robot. So the question is: what role can startups and technology play in democratising design?

DMM I feel that developing architecture through the processes of product-making — which require extensive validation and testing — is, in itself, already embedded with a means of ensuring quality. It brings together strong design, effective technology, and the intelligence of multiple disciplines. It’s an integrative effort that rarely happens in the context of affordable housing.

For me, that challenge of qualitative integration is both possible and incredibly compelling. For example, the systems we develop with WoHo are designed to make an impact in affordable housing, but we could apply the same systems in luxury housing. Our focus is on the core of the building — the systems, the structure, the components that truly need to function and endure. How a building is ultimately finished, adapted, or located is less important. As long as the “bones, muscles and organs” of the building are well designed, you can wrap it in gold if you want.

The key is that the essential quality and durability of the building should be guaranteed — and that, I believe, should be a right for everyone.

"How a building is ultimately finished, adapted, or located is less important. As long as the “bones, muscles and organs” of the building are well designed, you can wrap it in gold if you want."

GR I find it interesting that, looking at architecture over the past few decades, that it has become an extremely niche profession — one that excels at creating exceptional, singular works, but rarely produces the norm. And that raises a fascinating question: what if we flipped that on its head? What if we asked, how can we make architecture in large quantities? How can we make it accessible to everyone?

To do that, we need to reconsider the very model of architectural practice and even the business model behind it. It requires a shift toward approaches that are scale-oriented. This isn’t a new question — we’ve asked it before: what is architecture, and can we do good work in large amounts? That was once a central driver of modern architecture, and I think it’s time to revisit it now. Today, the challenge is about creating large-scale, high-quality architecture that is accessible and impactful for the many, not just a few.

JF I think the Eames’ captured it well in their motto: “The best, for the most, for the least.” That drive within late modernism really resonates in our work, I feel.

My interest in infrastructure can be partly illustrated by recalling an exhibition — if I remember correctly, at the Design Academy in Eindhoven — where designers were obsessed with recycling, like making ‘leather’ shoes out of mango skins. I reflected that in our fields — cultural or architectural — there’s historically been suspicion toward people who can do maths, use Excel, or grasp economic concepts. But when it comes to products that actually affect climate change, I find that approach problematic. We’re not going to save the world with mango leather shoes.

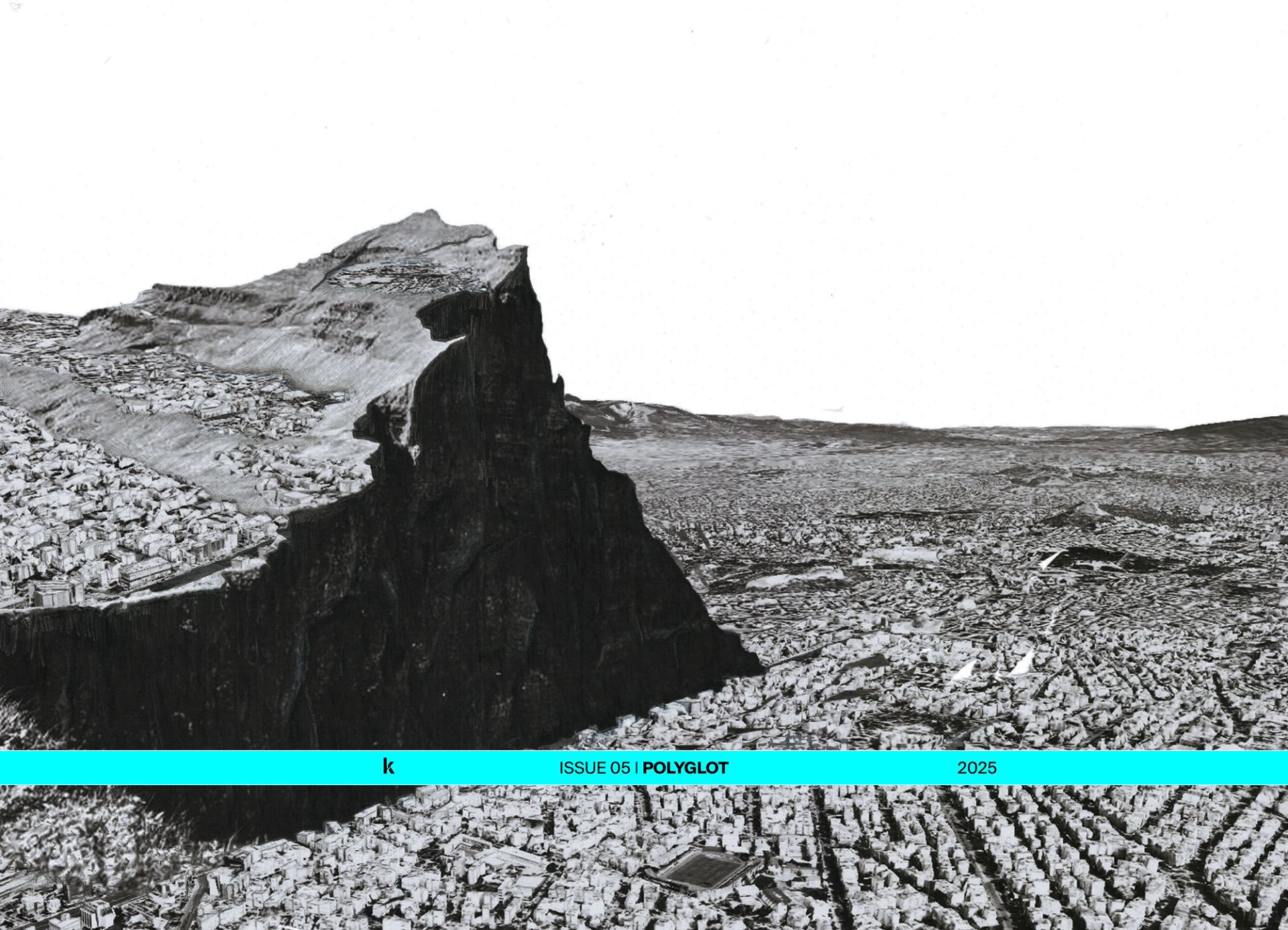

What we need is production at scale, and infrastructure is a phenomenal opportunity for that. At the same time, infrastructure — especially when combined with robotics — can possess qualities that almost evoke land art. And Ensamble’s work demonstrates that beautifully; it’s been an important source of inspiration for me.

"Infrastructure — especially when combined with robotics — can possess qualities that almost evoke land art."

SL I’d like to build on something you mentioned — the idea of democratic design, creating the best design for everyone. It’s a really nice concept. But in practice, if we look at something like the Bauhaus lamp, it’s actually the most important and expensive lamp — not an IKEA-style mass-produced product.

This brings us back to the question of industrialisation. We can have brilliant ideas, but their true impact comes when we bring them into industry. Startups can begin small, but the real change happens when we scale. As Gilles mentioned, I think the biggest transformations happen when we actually change industrial processes. All these ideas exist already. We have hundreds of system buildings, including wooden system buildings. We don’t necessarily need to invent entirely new systems — we could simply build on the ones we already know work.

What’s really interesting is that changing industrial processes — like incorporating robotics or digitalisation — can create moments where real change happens, because that’s when scaling becomes possible in a meaningful way. So yes, designing good products for everyone is a beautiful idea, but without industrial scale, it can remain quite exclusive in practice.

Fabio Gramazio I very much agree. I think there’s a fundamental tension between the completely generic and the super-specific. We’re trained to focus on the specific. Even if we were to engage with the generic, which I think is very important — we could have simply written or talked about scaling up, about how important these things are, or designed them and let them unfold. But if we truly engage and determine to address something ourselves, then we need to be able to accept a certain idea of the generic.

There are times when we face decisions that force us to interrogate whether we would kill our startup by saying no to something that strays too far from our core vision — a vision we cannot fully discard, nor should we have to. At such times, the choice becomes a rational one. It’s about assessing opportunities: is it better to scale up or to stay closer to our original path?

Many great attempts and ideas in the twentieth century failed precisely at this point — when that final, painful compromise wasn’t made. I don’t have a ready answer for how I would decide, in the moment. But if the argument for large-scale impact is serious, then this tension — and its consequences — must be confronted.

SL Every startup fails at some point — especially in the first round, failure is very common. As founders, we can also be optimistic and learn from those failures… Starting up is often a process of trying, failing, and starting again — sometimes repeatedly.

"Starting up is often a process of trying, failing, and starting again."

KOOZ Building on that, what support systems beyond academia are needed to support architectural entrepreneurship?

GR The key, obviously, is the investors. For me, one of the most important things is making sure that the conversations we have as architects also start engaging the people who can actually make these ideas real and help them scale. Over the past few years, some of the most interesting conversations I’ve personally had about architecture were not with other architects — they were with people in the investor community. I think that’s actually a useful rule for any architect: if you want to understand impact, don’t just talk to other architects.

DMM Since we’re on a panel about culture, I think it’s also worth talking about values. There are different types of investors, and increasingly, we see investors who care about more than just quick financial returns. If someone is only looking for fast profits, architecture and construction are probably not the right path — these sectors take time. However, if the focus is on mission, vision and impact, that opens up a completely different conversation. In that space, there are many investors and individuals who are genuinely willing to use their money to support meaningful change — and in that sense, I like to believe that we’re far from irrelevant.

"If someone is only looking for fast profits, architecture and construction are probably not the right path — these sectors take time."

JF I think a startup gives us the opportunity to take real initiative. For a long time, architecture has often been constrained by the vision of a third party — typically a developer — with an already-defined design intent. As such, your role becomes more about deciding what finishes to apply or what small adjustments to make, which dramatically limits the scope of architecture.

In that sense, after working on Ottico and Aectual, I’m on my third startup and finally get to author a third initiative myself. I think architects truly excel when they’re formulating that kind of initiative. That said, once a startup reaches an operational phase, it’s also entirely valid to shift focus — to keep developing, keep moving forward, and adapt to operational realities. Personally, I tend to step away when a startup becomes primarily operational.

KOOZ Thank you for bringing us back into values — and for all of your contributions.

* Silke Langenberg's keynote contains material from an ongoing research which refers to the works of two further members of the team which also include PD Dr. Robin Rehm and Dr. Sarah M. Schlachetzki.

Bios

Silke Langenberg is a Professor for Construction Heritage and Preservation at ETH Zurich. Her professorship is associated with the Institute for Preservation and Construction History (IDB) as well as to the Institute of Technology in Architecture (ITA). Since 2023, she is director of research and member of the department board. One of her latest SNF-funded projects deals with the role of patents in architecture.

Jelle Feringa is a pioneering architect and robotics specialist. Following his PhD research at TU Delft, he founded Odico Formwork Robotics — the first publicly traded architectural-robotics firm. In 2021 he founded Terrestrial, patenting “shot-earth” 3-D printing for large earthen structures.

Débora Mesa Molina is Professor of Architecture, Art and Technology at ETH Zurich and Principal of Ensamble Studio, the cross-functional practice she leads with her partner Antón García-Abril. Through their startup WoHo (World Home), they are currently developing strategies to improve quality and affordability in architecture by integrating offsite construction technologies.

Gilles Retsin is co-founder of Automated Architecture (AUAR), a London-based technology startup developing robotic micro-factories, timber-frame systems, and software platforms for sustainable, affordable housing at scale.

Fabio Gramazio is a Swiss architect, and Professor of Architecture and Digital Fabrication at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, ETH Zurich. He is also the co-founder of the architecture and design group Gramazio Kohler Research, which focuses on the integration of digital fabrication and robotic technologies into architectural design and construction.

The proceedings of the symposium ‘Startup Architecture: Venture as a New Mode of Practice’ may be explored further here.