Here’s an exercise: count the actions in your daily life that either produce or depend on some form of data. Looking up the weather, liking a post — each ephemeral action processes data, which in turn morphs from digital information to physical infrastructure. Laura Polkmane’s deep dive on hyperscale data centres — particularly in Denmark — demonstrates our data-hungry lifestyles in terms of their architectural and economic consequences.

KOOZ As our consumption of information continues to grow exponentially, hyperscale data centres continue to proliferate across our landscapes. What constitutes a hyperscale data centre — can you lay out the relationship between the data we process and the physical footprint of these structures?

LAURA POLKMANE Most people alive today — myself included — are immersed in an abundance of data, whether it is an email, a Google search, or streaming a video; we share an insatiable data appetite that lives in an abstraction called “The Cloud”. 90% of the world’s data has been generated within the past few years.1 However, this abstract, almost ethereal metaphor of “the Cloud” implies a spatial dimension. As data grows, so the global demand for data storage infrastructure grows with it, leading to the emergence of hyperscale data centres as a growing architectural typology. If we are the spectators and our digital information occupies the stage, then hyperscale data centres are every bit of backstage machinery and programs needed to keep the show running.

From systems of storage to systems of exchange, data centres orchestrate every single act of our data-permeated existence.

From systems of storage to systems of exchange, data centres orchestrate every single act of our data-permeated existence. These vast, almost fully automated structures are designed to accommodate expansive and ever-increasing volumes of data. Far from being mere larger siblings of traditional data centres, the hyperscale centre represents a radical intensification of space, power, and cooling capabilities. Each hyperscale typically boasts a footprint extending over hundreds of thousands of square metres, housing tens of thousands of servers that process and store exabytes of information. The architectural typology of a hyperscale data centre is characterised by modularity and efficiency, with standardised racks, raised floors and extensive cooling systems forming the bedrock of their design.

The relationship between our voracious data consumption and the physical incarnation of these centres is a dance of codependency.

In an introduction to the book “Datapolis,” Negar Sanaan Bensi and Paul Cournet describe data infrastructure as a many-headed demon, reshaping everything in its path while housing opposing forces and narratives within its unassuming facade.2 The relationship between our voracious data consumption and the physical incarnation of these centres is a dance of codependency. Part of my research was to identify these layers of extraction, such as surveillance capitalism, the digital divide, the mining of rare earth materials that are the backbone of our electrical devices, the sprawling power and water-hungry data centres that dot our landscapes, and the embodying material and energy demands of an increasingly data-driven world. The extractive nature of data is not necessarily a new subject, as the ontology and agency of data have been part of many debates. Considering the legal complexities, an important wave of discourse can be traced back to the establishment of WikiLeaks, while the significant energy consumption associated with data centres has long been highlighted by Greenpeace. However a less discussed, yet potent subject lies in the post-data centre environment. We are producing data at such an exponential rate that current storage methods will soon become inadequate. Molecular storage is emerging as a potential alternative, signalling the obsolescence of our existing infrastructure. This imminent obsolescence became a crucial trajectory for the project: how do we design for an infrastructure that is rapidly expanding yet destined to become the modern ruins of tomorrow?

KOOZ In the last few years, three hyperscale data centres have been completed in Denmark. What can we learn from the spatial and ecological consequences of these infrastructures upon the Danish landscape, both in physical and more intangible formats?

LP Data centre architecture has turned into a critical site of investment and innovation: a veritable playground for the nations that share reliable fibre optic cable grids, renewable energy grids, and cheap land. Denmark, among other countries, is recognising the lucrative side of hosting hyperscale data centres. The recent arrival of some of the world’s largest technology companies to Denmark (Apple, Facebook, and Google), coupled with the prospect of six more ‘hyperscales’, sparked my ethnographic interest in Denmark and the question: what is the entangled nature between the state and the data centre as a socio-political construct?

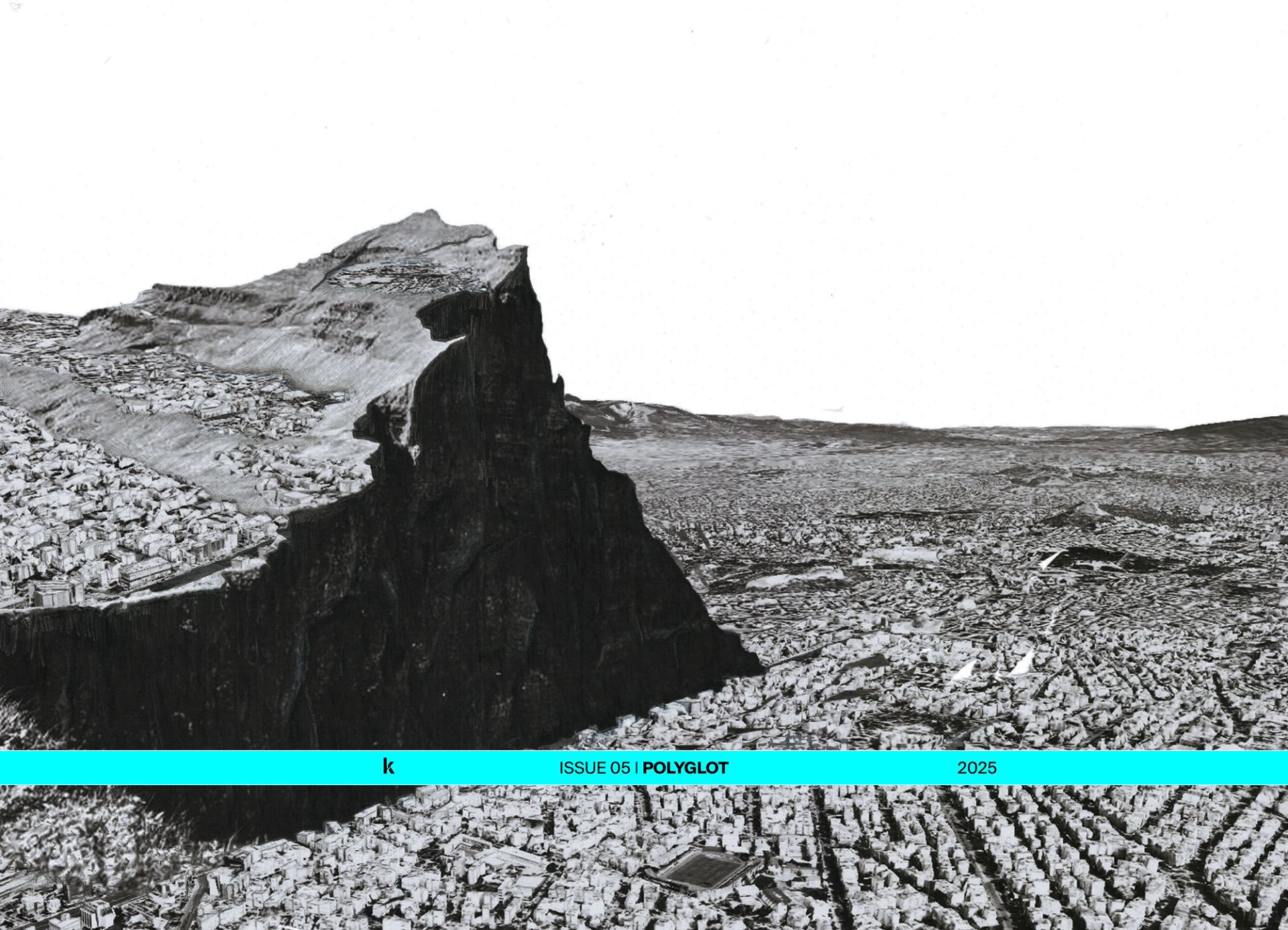

Moreover, it was the research done by artist Jacob Remin and philosopher Gustav Johannes Hoder, highlighting the environmental concerns, which demonstrated that these nine hyperscale centres will add an extra 22% to the energy grid by 2040 — the equivalent of powering over three million new homes.3 Despite this quite terrifying statistic, Denmark’s energy and climate agreements remain conspicuously silent on this front. Lying within is a compelling paradox: the state's enthusiastic embrace of digital infrastructure juxtaposed with a deafening silence on its ecological repercussions. Physically, these data centres are monumental impositions upon the landscape, converting under-utilised lands and greenfield sites into highly controlled environments. The sheer scale of these centres necessitates extensive land use, often leading to the displacement of existing ecological systems. They exert significant pressures on local resources, notably energy and water, while their heat emissions alter local microclimates. These structures introduce a new logic of space — one that privileges data over context, reconfiguring local economies and communities. Denmark’s experience underscores the duality of progress and disruption inherent in hyperscale data centres, as they anchor the global digital economy while reshaping the local environmental and social fabric.

KOOZ The project investigates the architectural typology of the hyperdata and advocates for an alternative approach that emphasises conscious resource use and post-data use. What kind of models has the project investigated and what opportunities for change has it identified?

LP A couple of years back, Apple announced they wanted to expand their existing hyperscale data centre in Viborg, Denmark, multiplying the typology with three additional data centres on the site. This expansion became a catalyst for my examination of the conventional data centre typology. Rather than settling for the status quo of mere efficiency, my project envisioned the site as a testing ground for an architecture that embraces deliberate resource use and possible post-data applications. Yet there was a need to embrace a pragmatic understanding of the expansion; the need for a certain amount of server racks, adjacency to the existing infrastructure networks, the need to first utilise existing hyperscale waste heat, and then consider possible tweaks in the planned expansion that might propose a paradigm shift. This meant moving away from an isolated monument, and instead seeing a data centre as a possible hyper contextual component.

In theory, the idea of using the excess heat of data centres for district heating purposes is widely discussed; however hyperscale data centres are often too far from central heating systems, so trying to find a more local solution for waste heat became an important lever. Besides the more technical models explored was the need to demystify the physical and operational aspects of data centres. By adding a layer of public access and transparency, one can imagine such a facility operating as a catalyst for discussions on data ethics, privacy, and wasted data resources.

KOOZ The final act of your project discusses the possibility of a future when data will be stored in a molecular form presenting a re-use system that enables the transition of data space into a conditioned setting for ongoing agricultural purposes. How would this future reconfigure the relationship between individual, data and territory?

LP When I started to investigate the context and the existing data typology, there was a noticeable relationship between the excess resources generated by the data centre and resources needed on the site for agriculture research purposes, by the adjacent research campus. With that, one of the models investigated was the concept of co-location; the possibility of leveraging the excess heat and water generated by data servers to support greenhouse farming and aquaponic systems. Technically, this model was explored by tweaking the understanding of the two main data centre isles, known as the cold and hot aisles, and introducing systems of exchange. Moreover, I saw the possibility of envisioning a data centre as a dynamic structure that can be easily reconfigured or repurposed as technological needs evolve. For instance, as molecular data storage becomes viable, existing data centres could transition into highly controlled environments for future agriculture purposes. This would be a direction that is very much aligned with Denmark's decarbonisation vision, to change its monoculture agriculture practices that take up a large portion of Denmark's land use to vertical farming solutions.

While the future of molecular data storage might seem like a utopian dream, it is very much aligned with the trajectory of information technology. The potential of storing our data in the DNA cell of a tree allows profound reconfiguration of the relationship between individuals, data, and territory. The integration of molecular data storage would significantly diminish the spatial demands of data infrastructure, allowing for the reclamation and potential rewilding of land currently dedicated to hyperscale facilities.

Ultimately, this future reimagines data infrastructure not as a burdensome imposition upon the landscape but rather as a dynamic, multifunctional asset that enhances both human and more-than-human thinking.

In this future scenario the boundaries between digital and physical landscapes blur, as data centres evolve from secluded figures into multifunctional spaces that support both technological and ecological processes. For individuals, this transformation signifies a shift in the perception and interaction with data. No longer confined to abstract or distant repositories, data becomes a tangible, integrated element of the physical environment. Ultimately, this future reimagines data infrastructure not as a burdensome imposition upon the landscape but rather as a dynamic, multifunctional asset that enhances both human and more-than-human thinking. But what it also enables is the ability to repurpose data centre infrastructures for alternative uses and to rethink data centre design as ephemeral and adaptable. The fun part for me was moving from the masterplan scale to more detailed, conscious thinking about how we can repurpose data server racks, raised floor systems, and wiring networks that dominate these centres.

KOOZ Although the issue of data is surely partly architectural, it is also inherently tied to questions of ownership and legal complexity that go hand in hand with surveillance capitalism. What role can architecture play within these complex frameworks?

LP A central theme at the Urbanism and Societal Change studio — at the Royal Danish Academy — was architecture’s capacity to interrogate and influence the broader socio-political frameworks it inhabits. However, when thinking of data, a big issue is the fractured governance of the internet across different global zones. It is very hard to imagine the internet operating in its early form — like ARPANET, the open-source exchange system between researchers called back in the 70s — it feels like wanting to conjure a digital Eden that is long gone. As most of the internet today is dominated by privatised monopolies, an important issue to explore was the idea of a cooperative infrastructure network — that is, to look at data architecture as a space for storing information while operating in many modes of collective use. In many ways, I think architecture can play a pivotal role in shaping more equitable and transparent systems — it can be a medium for making the invisible visible. This feels similar to the thinking of James Wines' early designs of supermarkets and his interrogation of typical commercial environments.

In many ways, I think architecture can play a pivotal role in shaping more equitable and transparent systems — it can be a medium for making the invisible visible.

One of the core questions was to understand how to make this typology open, or more literally how to de-fence it. Most hyperscale data centres are delivered as standardised packages, owned by big tech US companies. While such rigid structures may suit the American regulatory landscape, Denmark, within the EU framework, provides a ground to reshape and rethink the way we structure our infrastructure systems. By designing data centres with an emphasis on transparency and public access, one can demystify these black-boxed structures and foster greater awareness of the issues at stake. In many ways, it implies a transition from isolated objects to dynamic nodes in a cooperative network. Through such acts, architecture can try to advocate for the decentralisation and democratisation of data infrastructure and, more importantly, allow us to think about where our data resides, what even is data sovereignty, and what it means to challenge the monopoly of surveillance capitalism.

Bios

Laura Polkmane is a recent graduate from the Urbanism & Societal Change master’s programme at the Royal Danish Academy. Her graduation project delved into the dynamics of data infrastructure space, navigating the materiality and agency of data, advancing her nuanced interest in the interplay between architecture and technology. Laura has previously studied at Riga Technical University and has worked across different scales in Riga, Amsterdam, finally joining Gehl architects in Copenhagen. Throughout her time at different offices and the Royal Danish Academy, Laura has developed a diverse portfolio of projects ranging from large-scale strategic plans to detailed architecture and object design. Her thesis project is also currently shown in the exhibition "NEW Design and Architecture", at the Royal Danish Academy, Denmark.

Federica Zambeletti is the founder and managing director of KoozArch. She is an architect, researcher and digital curator whose interests lie at the intersection between art, architecture and regenerative practices. In 2015 Federica founded KoozArch with the ambition of creating a space where to research, explore and discuss architecture beyond the limits of its built form. Parallel to her work at KoozArch, Federica is Architect at the architecture studio UNA and researcher at the non-profit agency for change UNLESS where she is project manager of the research "Antarctic Resolution". Federica is an Architectural Association School of Architecture in London alumni.

Notes

1 “Data Growth Worldwide 2010-2025,” Statista, accessed September 22, 2023, [online]

2 Negar Sanaan Bensi, Paul Cournet, “Introduction: On Datapolis”. Datapolis: Exploring the Footprint on Our Planet and Beyond, ed. Paul Cournet (Rotterdam: Nai010 Publishers, 2023), p. 9

3 James Maguire, Ross Winthereik Brit, “Digitalizing the State: Data Centres and the Power of Exchange,” Ethnos 86 no. 3 (May 27, 2021), pp.530–51, [online]