A conversation with Campo’s Matteo Costanzo and Luca Galofaro, and Citygroup’s Violette de la Selle and Michael Robinson Cohen on how each of their collective activities change the norms of curatorship, pedagogy, activism, and professional practice, and tackling the role of the discipline at different levels.

VALERIO FRANZONE / KOOZCan we start with your respective stories; how and why did your initiatives establish themselves? Can you also introduce your members?

MATTEO COSTANZO / CAMPOCampo started in 2015; we were very interested in doing a curatorial activity connected to a physical space. We are Gianfranco and I — the two partners of the Rome-based firm 2A+P/A — as well as Luca Galofaro, partner of the Roman firm LGSMA_ and Davide Sacconi, a scholar based in London. We are from three different generations: Luca is eight years older than Gianfranco and myself, while we are eight years older than Davide. These generational gaps represent different ways of looking at architecture as experience and intention. Still, we all share the will to understand and engage with curatorial work as a project per se.

We rented a small warehouse facing the courtyard of our office building, an old mill connected to the Roman aqueduct, and we started organizing a workshop. Campo is not a gallery but something similar to the ‘artist project rooms’ where people share discussions. Our space and its location are fascinating and contribute to our curatorial sensibility. It's an idea in-between times, on one hand related to the powerful heritage of Rome; on the other, it overlaps with our contemporary and international interest in architecture.

MICHAEL ROBINSON COHEN / CITYGROUPWe started in 2017 in New York City. At that time there wasn’t a formal group; some of our classmates from graduate school and people we knew from professional life were eager to have a different type of conversation about architecture and the city. We therefore organised debates.1 These were not formal academic debates where two people stand in front of a room and present their arguments; rather they were more casual. We were interested in finding a different way to talk about architecture, something nonhierarchical and multi-directional. There was a desire to encourage people to express strong opinions while also listening to each other — to prove that we could disagree and argue respectfully. Needless to say, the debates didn’t end with a winner or with the declaration of a resolution as such.

VIOLETTE DE LA SELLE / CITYGROUPWe were interested in the content of our discussions; we felt it was important for a debate that allowed arguments, oppositions, and where it was acceptable to change one’s opinion. We wanted new streams of knowledge exchange. We started building on that, and in 2018, we found a small space. That space suddenly opened up other exciting possibilities: meetings became more regular, we had walls upon which we could host and curate exhibitions, and a permanent address.

MRC / CITYGROUP Those walls create a frame that sets our activities and gatherings in a specific place. The storefront is also positioned a few steps below grade, which creates a unique vantage of the sidewalk and street. It’s connected to, yet set apart from the context, which is in a way how we see our relationship to the city.

KOOZ How many and who are you? Is there a reason you don’t list your names on your website?

VDLS / CITYGROUP There are a few different ways of answering your question. One is that it's a fluctuating group, and participation defines membership. So, if 36 people come to a debate, then Citygroup is those 36 people.

MRC / CITYGROUP It's also about foregrounding collective effort, but at the same time we recognize the importance of not erasing the individual and their labour. When we first secured the space, there were about 14 people actively involved: Luke Anderson, Ali John Pierre Artemel, Cody Campanie, Michael Robinson Cohen, Miles Huston, Sebastijan Jemec, Merica May Jensen, Georgia McGovern, Violette de la Selle, Will Sheridan, Radhika Singh, Amy Su, David Tasman, Alice Tai. People plug in and out based on their availability. The group fluctuates because everyone has other jobs and commitments; we really do try to emphasize the idea that participation defines membership and are very open to people getting involved.

"Institutions, when dealing with the knowledge of architecture, are often not capable of understanding the specific discourses that come out from new generations, dialogues between the urban and the rural, debates about pedagogy or radical approaches."

- Matteo Costanzo / Campo

KOOZ Describing Campo and Citygroup as architecture galleries feels reductive. You operate through various modes of practice and at their intersection: curatorship, pedagogy, research, publications and so on. Can you tell me about your approach? Is your work a critique of professional practice, or a way to develop it?

MC / CAMPO True, we cannot call Campo a gallery. Since the beginning, communicating what it is has been problematic — we have always described it rather generically, as a space. Contrary to a commercial gallery, we don't sell artworks, we don't represent artists or architects, and we don't impose a particular vision. In Italian, 'campo' means many things: a square like Campo de Fiori or a wider urban area like Campo Marzio in Rome, a sports or agricultural field. Campo can be translated with 'field'. Usually, a field is big enough to contain much information, yet it defines a space that is not infinite, which is our philosophy. Another aspect that, from the start, differentiated Campo from a gallery is that it is an intimate attempt related to specific liturgies: "Campo is a space to debate, study and celebrate architecture". Today, celebrating architecture is an issue, so we are trying to understand how to translate this into our activity. We believe liturgies of knowledge can help our audience understand this specific viewpoint. We organize workshops, talks, and exhibitions, three activities that sometimes mix. Everything is organised precisely and has specific liturgies — rules and methodologies — within the space. Everything overlaps with sensibilities, possibilities, and limits related to money, space, and time because Campo is an independent project detached from commercial logic. More than a critique of practice, Campo was born as a critique of a certain problem: institutions, when dealing with the knowledge of architecture, are often not capable of understanding the specific discourses that come out from new generations, dialogues between the urban and the rural, debates about pedagogy or radical approaches. Then too, we wanted to interact with Rome: it’s a city that is not so relevant in contemporary architecture yet can offer many occasions to reflect. So, Campo became a place where people could discuss and organise exhibitions, talks, or workshops faster and easier than in any institution.

Of course, there are many issues associated with professional practice, and how our firms interpret it is probably not the norm. That's why we thought the main problem was how to deal with architectural knowledge. In all our activities, we aim to understand what architecture means.

KOOZ By ‘critique’, I mean trying to understand what architecture could do in order to go beyond its status quo.

MC / CAMPO I agree. It is strongly associated with pedagogy, and we tackle it in our teaching activity in London and by organising activities in our space using Rome’s incredible historical archive. However, we also do it by manipulating the case studies we select as our activities’ prompts. For instance, the origin and inspiration of our first exhibition and workshop, The Supreme Achievement,2 was the Twelve Ideal Cities by Superstudio: we invited twelve offices to reimagine that project in the exhibition, which then became the brief for the student workshop. We reiterated this methodology many times. The issue is not about nostalgia but being able to translate old knowledge into contemporary practice. Then, we opened to the concept of 'misunderstandings'.3 We worked with the archive of the FRAC Center of Orleans to enable twelve offices to reinterpret the ideas that drove the projects we selected. It is an interesting exercise to manipulate history and to subvert its nature to make a contemporary project.

VDLS / CITYGROUP Campo resists the label of a gallery similarly to us. We don't have a portfolio of artists and we don't sell anything, but we are a space where people exchange ideas and generate projects. Our walls are an opportunity to exhibit.

Our activity is a critique of professional practice because of specific lacuna in architecture in New York. Here, practice is defined very much by its limitations, including risk, which means money and legal ramifications. Those two constraints subdue conversations about what architecture is in this city: you can practice as an architect, design significant buildings and work without addressing the public sphere — contrary to what has fascinated architects for centuries and is essential in a city. I'm not blaming practitioners for this, but the limitations. So, Citygroup tries to put together the idea that architects, in their creative pursuits, are interested in how people participate in the built environment.

"In some ways, Citygroup is an adversarial critique of professional practice. An effort to move outside to look inside."

- Michael Robinson Cohen / Citygroup

MRC / CITYGROUP In some ways, Citygroup is an adversarial critique of professional practice. An effort to move outside to look inside. Still, we started because we were hopeful about practice and we care deeply about built, material architecture. Two aspects of professional practice are at the centre of our critique. One is how architects relate to each other, and the other is the limits set by economic and political forces in the city. Especially in New York, professional practice situates architects in a very rigid relationship with real estate and its hold on the city’s development. The name 'Citygroup' is a reference to the financial entities that shape the city. Perhaps it’s too optimistic, but our aim is to delineate a small space outside of these structures where architects and non-architects can think, talk, and create differently. Our gatherings and activities intend to be less framed by the expectations of professional practice. They are not hierarchical, but are rather informal, experimental, and inclusive.

VDLS / CITYGROUP We began with a manifesto expressing our foundational principles and concerns. One is about creating solidarity among architects to generate a new practice model. We are not a practice, but we can exemplify how architects engage with the universe beyond architecture.

KOOZ You just mentioned your name; Citigroup, with an ‘i’ instead of a ‘y’, is a huge financial company.

VDLS / CITYGROUP The name 'Citygroup' comes from the bank Citigroup, which sounds like an urbanism practice; they wanted the word 'city' because it's prestigious to be associated with the city, which is a living organism. So, we reclaimed the name away from them.

MRC / CITYGROUP We see the bank’s name as an assertion that the city is owned by financial institutions. Due to the proliferation of the bike-sharing programme Citibike, the word “Citi” appears on almost every block in New York. We take offense to this. For us, reasserting the ‘y’ is a small act of resistance. It claims that profit should not dictate life in the city. This linguistic play might seem superfluous, but it professes a sentiment about how the city operates that guides all of our activities.

VDLS / CITYGROUP Our manifesto includes a quote from medieval Germany: "City air makes one free." As living in the city freed one from feudalism. However, this notion of freedom occurs within the C I T Y, not the C I T I. The outsized role of financial institutions in the city's operations and development is passively accepted, and adding friction here anticipates something different for the city.

"The idea that we developed with Campo is about improving the architectural project without proposing architecture as an answer. We work with the concept of 'protocols', a set of rules to allow a range of people to work on a given project at different curatorial moments and share ideas about architecture."

- Luca Galofaro / Campo

KOOZ The US and Italy represent two different economic and urban situations, and so is the role of professional practice. Here, architects' dependency on real estate is opening an interesting debate in academia and among the new generations of practitioners. There's often a search for a new role for architects and new modes of practicing. It's an issue many are tackling.

LUCA GALOFARO / CAMPOFour of us are practitioners, but our professional activity is detached from our cultural work with Campo. Still, our mode of cultural practice — which is based on participation and sharing ideas — expresses our attitude towards architecture and professional practice. Participation and sharing constantly drive our individual professional projects and communal cultural work. They are related to an idea based on generosity and offering our point of view to others by listening to them.

You will receive different answers if you pose this question to Matteo, Gianfranco or Davide. Yet, Campo has little to do with professional life beyond the driving principles I mentioned, representing our general approach to architecture. Understanding what architecture could be for the city is very important in all my forms of practice. So it is for Campo. We want to define an idea of architecture but not to prescribe an architectural project. The idea that we developed with Campo is about improving the architectural project without proposing architecture as an answer. We work with the concept of 'protocols', a set of rules to allow a range of people to work on a given project at different curatorial moments and share ideas about architecture. It’s not about language, style, or other typical architectural tools but to open a discourse about architecture.

KOOZ Fascinatingly, Campo and Citygroup are very different but share many things in common. What is the scale of the issues you tackle? Do you respond to your cities' societal and environmental urges, global ones, or is there a transscalar attention behind your approach and focus?

VDLS / CITYGROUP There are different ways of talking about scales. Our current exhibition is centered on the Poots, a tiny sunken space — nine square feet — between our space and the sidewalk. It's a space waiting for an intervention in the city at a microscopic scale. Still, at the larger end of the spectrum, we're also interested in how zoning armatures define the city. We don't have hard limits in either direction. The recent show Geo-Fantasies,4 organised by Andrea Molina with Reem M. Yassin, was about the United States’ extensive western landscape and carbon sequestration, trying to answer the broader scale of the problem: pollution as a global phenomenon.

MRC / CITYGROUP We have been particularly focused on issues related to our immediate context, namely Manhattan’s Lower East Side and Chinatown. Our group formed at a moment when this part of the city was undergoing intense gentrification and real estate development. The East Village, the neighbourhood to the north, was ‘downzoned’, so construction activity moved to the south. One of our first group activities was joining a community march contesting the construction of luxury towers along the waterfront in Chinatown. We have since embedded ourselves in community and activist organisations that are fighting displacement and advocating for affordable housing. Our participatory approach runs counter to the typical models of architectural activism and engagement, which often maintain barriers between architects and the community. Instead of seeing the community as something to engage, we have worked to become part of the community. This required showing up for meetings and events at first, and spending a lot of time listening. Ultimately, we introduced ourselves as architects and artists and offered our skills to support the community efforts. I guess here ‘participation’ refers to our participation in the life of the neighbourhood. A significant portion of our work has involved using architectural representation to demystify the language of city-planning and zoning.

VDLS / CITYGROUP Citygroup began around debates, and conversations that can be had at different scales. Still, some conversations are more insular to architects. Hence, we reflect on how to communicate architecture to non-architects.

MRC / CITYGROUP We've also used our exhibitions to draw architects into these community efforts. Around the time of the march that I mentioned above, we organised an open-call exhibition that asked architects to redesign the floorplan of a luxury tower on the Lower East Side. We see this curatorial activity as a type of political organising that breaks down the barriers set by professional practice.

"Citygroup began around debates, and conversations that can be had at different scales. Still, some conversations are more insular to architects. Hence, we reflect on how to communicate architecture to non-architects."

- Violette de la Selle / Citygroup

KOOZ So, your transscalarity — from carbon sequestration to housing issues in the neighborhood — is a device to turn speculative ideas into precise and feasible actions, forfeiting the theoretical realm?

VDLS / CITYGROUP Some projects lend themselves to this more seamlessly than others. This is particularly true following a close reading of a neighbourhood zoning proposal and our attempt to make it legible to non-architects. The content we produce for our shows and the visual imagery we create work similarly, to provide tools to community movements.

KOOZ Can you reflect on the same questions for Campo?

MC / CAMPO Campo is a project open to many things but doesn't offer solutions; our obsession is understanding how to talk about architecture. Referring to the scale, we always look at architecture as directly related to the city; they are not detached. In the debate about the origin of architecture — which opposes the theory of the Primitive Hut as an isolated shelter just protecting from climate adversities and animals versus the theory of the Primitive Hut as a group of units already defining a community — we embrace the second interpretation. Through this, we can work to tackle environmental and social issues because that is the role of architecture. Another essential element is the above-mentioned notion of 'campo' or field — because the dimension of the problem is so big that it's crucial to establish a common ground to find systems of sharing knowledge as the base of the discussion: liturgies, topics, and the rules directing our activities, which are consistently as precise as possible. Ultimately, the limits we have set become our most effective device.

"We consider architecture a humanist discipline, as it can't be reduced to the construction of space."

- Matteo Costanzo / Campo

KOOZ Would you say that you analyse and develop general architectural methodologies rather than analyse and tackle specific issues?

MC / CAMPO We consider architecture a humanist discipline, as it can't be reduced to the construction of space. A text and a picture of architecture also constitute architecture; this is very crucial if we look at the history of architecture. We cannot forget that it's a discipline through which we can interpret our condition. That's why we tend to think that our exhibitions are not only for architects; what they offer is not just related to the discipline of architecture: they always provide a broader point of view, reading the world, the complexity of our societies and the role of architecture within that.

MRC / CITYGROUP Matteo's notion of common ground resonates with our work. Creating a shared ground for unexpected interactions between architects, other professionals, and the public is our primary concern.

KOOZ I agree with the broader vision of architectural practice, which is not just professional practice; there are other practices: research, curatorship, pedagogy, etc. Understanding this issue is fundamental to the discipline.

LG / CAMPO But this is not the common idea shared by the profession, and it's a concept shared by a few of us. Campo is a gymnasium for us, precisely because it allows us to engage in many possible ways to practice architecture.

MRC / CITYGROUP One of our most important activities is a weekly get together that we call ‘circolo’ (We first encountered this term in Margaret Kohn’s book Radical Space: Building the House of the People).5 After everybody gets off work, we gather in our space in Chinatown to eat dumplings, drink beers, and talk. Sometimes we discuss architecture but it's really just a chance to be together.

KOOZ What you just said introduces the issue of your relationships — how architects relate to each other plays a crucial role in our profession. What is your approach? Do you operate individually within a shared structure or as a collective mind?

LG / CAMPO The collective mind represents precisely how we operate. When we start a project, I might arrive with my idea; after a while, I start defending Matteo's idea, which Davide has already transformed. Identifying a project's intellectual owner is difficult because everything we do emerges from discussions. Our approach is based on collective thinking, and this shared vision gives the architectural project different values.

"The collective mind represents precisely how we operate. When we start a project, I might arrive with my idea; after a while, I start defending Matteo's idea, which Davide has already transformed."

- Luca Galofaro / Campo

MC / CAMPO Authorship is often an obsession. It’s necessary when referring to professional practice — where there are specific responsibilities — but with Campo, it is different. Our development process is not linear, sometimes things become very ambiguous: we choose a topic, invite architects to discuss it, and later students elaborate on everything. In the meantime, there's a curator coordinating everything. With Campo, we are free to erase the author of any decision or output.

VDLS / CITYGROUP We're constantly balancing celebrating our collective mind without erasing our individual opinions and work. It's a delicate balance, and we never apply the same method. Still, we insist that what we present in our space never belongs to a single author. We're invested in this dialogue that makes our communal process understandable, favouring multiple authorships more than the celebration of one person. I philosophically believe that the hero-author doesn't exist and that every author exists thanks to the work of others. We prefer to foreground the idea that groups produce work.

MRC / CITYGROUP In order to do this, we dedicate a lot of time to establishing structures and methods that allow us to work collectively. We call this ‘group work’ and it’s an ongoing effort. Our hope is also that new people will plug in and use the space to pursue their own ideas. We are particularly interested in supporting emergent or less established people who don’t have access to the larger, more protected institutions in NYC.

KOOZ Publications constitute another aspect of your practices. Campo has produced several books and recently presented Zibaldone, a publication that rethinks the canonical anthological format and the book as an object. Tell me about the editorial strategy; is the book a testament or a moment to reflect before taking another step?

MC / CAMPO Zibaldone6 was intended as our activity anthology from the beginning. However, the problem was translating this knowledge into something autonomous. Finding a precedent that could gather many things like talks, workshops and exhibitions regarding architecture, photography, art, and various specific research was challenging. We looked at the history of books until we encountered the word 'zibaldone', which in Italian means many things — from recipes with various ingredients to books containing notes without a specific order — two things we judged negatively because they are an accumulation. At the same time, we found something positive in these examples too — they could represent a discussion made through fragments, where these fragments could be the outcome of our activities. Then we met Valerio Di Lucente, the book's designer and publisher Veii, which taught us many things about the book format, including its objecthood and autonomy. The issue was that zibaldone books are usually composed of words, while Campo's work is strongly related to the production of images. Our Zibaldone is divided into two parts: the first is textual and compiles the work of more than a hundred authors, while the second is an atlas collecting elements from our big, accumulative archive. Thanks to Valerio, we found how to translate this amount of information and knowledge into something related to the dimension of the published object.

LG / CAMPO Zibaldone is a way to elaborate our archive and transform it into an atlas. It also reproduces our space, using the cut-up technique similar to that of William Burroughs in Naked Lunch: when he didn't have ideas, to avoid stopping writing, he cut parts of his text, relocated them, and restarted writing around those elements. This method of recomposing our experiences provided a new meaning to all kinds of ideas about architecture from the people who passed through Campo. It's fascinating how Valerio created a new narrative that allows Zibaldone to provide the reader with what Campo was as a space and methodology.

Campo is not dead. It is moving to a different dimension — thanks to Matteo, Davide, and Gianfranco, who are teaching a diploma unit at the Architectural Association. Our methodologies are now instrumental in transforming that space into an architectural pedagogy that, as part of an academic path, is structured quite differently from the workshops that we organised. Transforming our thinking and discourse about architecture in another practice is a crucial evolution of our work and is a new form of experimentation.

"Citygroup is a small space that can't contain too much information; the more precise the message, the more successful the exhibition."

- Violette de la Selle / Citygroup

KOOZ Citygroup has also produced several non-canonical publications, experimenting with various formats. Can you discuss these?

VDLS / CITYGROUP During the Manifesting Manifesto exhibition, we gave visitors our own manifesto, which they were welcome to mark up and pin on the wall. With Évita Yumul, we made a zine of that exhibition: it’s a printed collection of all the marked-up and annotated manifestos. At the end, there is a blank page to add more reflections that can be mailed back to Citygroup. The catalogue therefore perpetuates the exhibition, giving visitors a “posthumous” chance to participate.

Citygroup is a small space that can't contain too much information; the more precise the message, the more successful the exhibition. Our exhibitions tend to reinforce a message or present a provocation but with a didactic intent. Our publications are informal and encapsulate our shows to extend them in time.

MRC / CITYGROUP Then there is the Citygroup bulletin, an initiative led by Georgia McGovern and Sebastijan Jemec. An artist is invited to create a work for the fence outside our storefront that responds to and expands on the exhibition or activity on view within the space. This work then acts as a sign or billboard. You might also consider our project Off the Fence as a type of publishing. For the project, a series of posters were covertly adhered to the construction fence of a luxury tower in our neighbourhood. The posters, which were organized in an alternating pattern of bright colors, displayed quotes from local residents and media outlets pertaining to real estate development in the city. The posters created a dialogue across their expanse and also intended to converse with people passing by. Like the debates that we first organized, the bulletin and the posters are an effort to make discourse.

KOOZ I like your continuous activism and guerilla tactics in publications on social-urban issues.

VDLS / CITYGROUP The term 'publication' implies making something public. Consequently, these examples are publications, even if they don't have an ISBN. We use these publications to advocate for and educate the public about social-urban issues, such as new zoning regulations, new developments, and what affects the built environment in our neighbourhood.

KOOZ What is Campo’s long-term agenda?

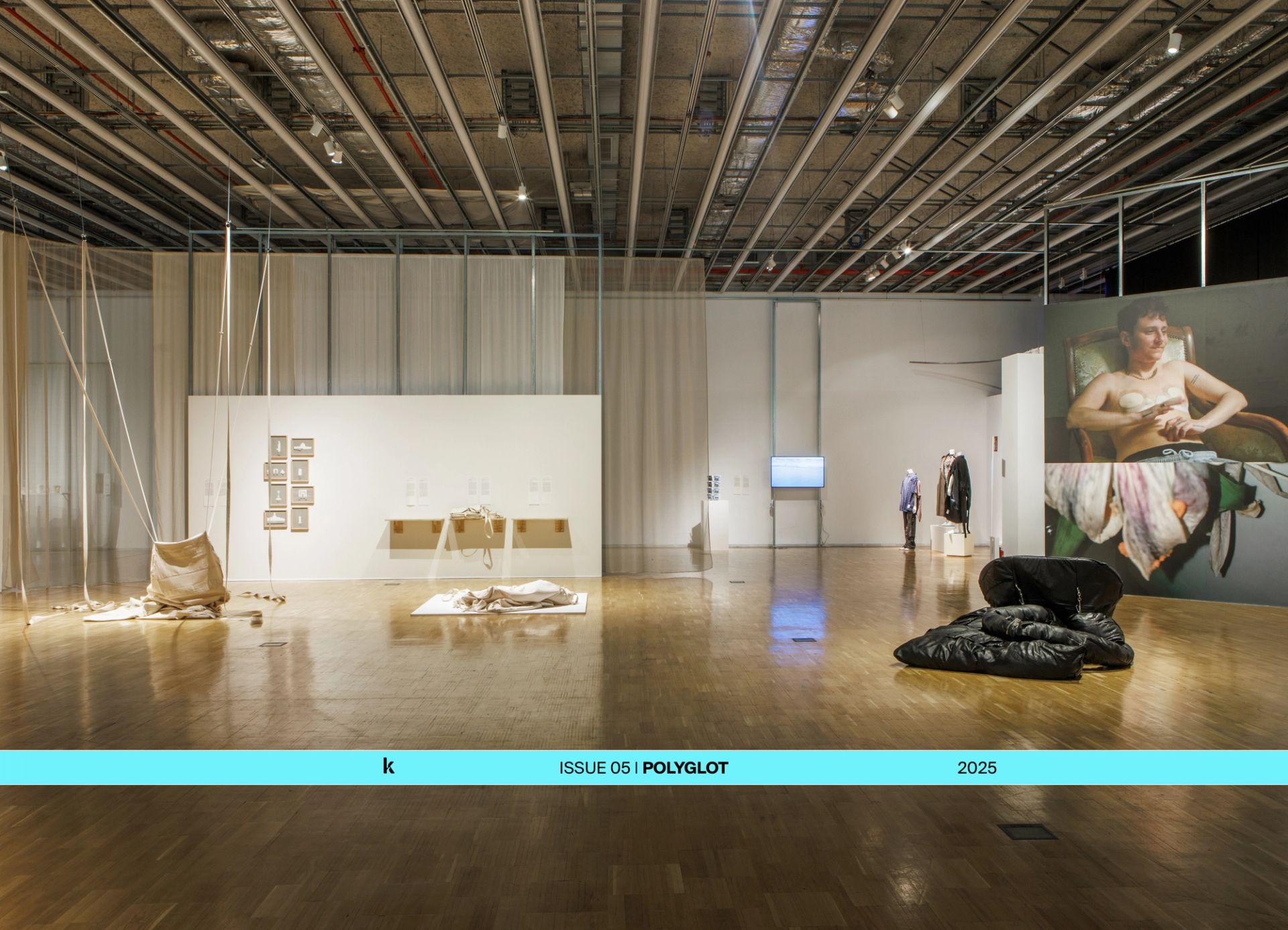

MC / CAMPO Currently, we are promoting Zibaldone and continuing to teach in the UK. Then, we will be the guest curators at the Fondazione Pastificio Cerere in Rome, where we made an exhibition two years ago and will exhibit again in February, under the heading Aperture.7 Of course, it's completely different when you are a guest instead of having your space, but at a certain moment, we realised that our space was no longer the focus of the project.

In the future, we'd like to establish an independent school, which we believe to be the only project that can enhance Campo's approach. We want to focus on pedagogy and architectural knowledge, translating the methods we apply in space into something that can be shared with new generations, and to bring into discussion many different sensibilities — even if doing so will probably change our whole attitude. In Rome as well as in international discourse, the role of the school is crucial. We appreciate teaching at the AA, but we still recognise that some issues cannot be addressed outside of an independent institution.

"I'm very optimistic about the debate framework that has defined us. It has permitted us to evolve but also stay consistent in a dialogical way."

- Violette de la Selle / Citygroup

KOOZ What is Citygroup’s long-term agenda?

MRC / CITYGROUP To avoid becoming too rigid and structured, while building the necessary systems for the group to productively work together and for new people to get involved. As we become more established, hopefully we can pursue ways of staying informal and accessible. Refusing to ossify as we pursue meaningful ideas and projects would feel like a success.

VDLS / CITYGROUP I'm very optimistic about the debate framework that has defined us. It has permitted us to evolve but also stay consistent in a dialogical way. If we keep discussing, we will move from the concerns that defined us in 2017 to the new ones that will define us in 2027. This is a place for experimentation — and we have no money, which is both a restriction and a potential. I'm not glamorising austerity, but being forced to make things inexpensively has stimulated us to find new solutions.I hope this spirit continues to inform how we work and give us, our partners, and our audience new opportunities. This will allow us to continue being a place where different ideas can mix.

Bios

Matteo Costanzo is an architect, founding partner of 2A+P/A Associates, and co-coordinator of the Laboratorio Roma050, a research group directed by Stefano Boeri. He has collaborated with the magazine Domus and written several texts and essays for international magazines and books. He is a co-founder of the magazine San Rocco and the space Campo in Rome. He has exhibited research, works, and installations at the 1st Orleans Biennial, the 2nd Seoul Biennial, the 5th Lisbon Triennial, the 14th, 12th,and 11th Venice Biennials, the FRAC Center in Orleans, the CIVA foundation in Brussels, the NAI in Rotterdam, the V&A in London, the Architectural Association in London, and the MAXXI in Rome. He has been a visiting critic and runs workshops in many schools in Europe, including IED, Rome; Naba, Milan; Domus Academy, Milan; Syracuse University, London; Cornell University, Rome; University of Miami, Rome; the TU Munich; Sandberg Institute, Amsterdam; Academy of Architecture, Mendrisio. Since 2017, he has taught in the studio ADS10 at the Royal College of Art in London, and from 2022 in the unit Diploma 20 at the Architectural Association in London.

Violette de la Selle is an architect and educator based in New York City. Violette earned her Masters in Architecture at Yale and her Bachelor of Science in Architecture from the University of Virginia. She is a founding member of Citygroup. Violette has worked as a project manager with Becker + Becker since 2020 on renovating and transforming the Pirelli Building in New Haven into the energy-pioneering Hotel Marcel. She has previously worked at SHoP Architects in New York and Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners in London. Violette co-edited the journal Perspecta 49: Quote. Violette has published writing in Exhibit A: Exhibitions That Transformed Architecture, E. Pelkonen, Ed. (New York: Phaidon, 2018), and San Rocco 66. Violette is currently teaching design studios at the Yale School of Architecture.

Luca Galofaro is an architect, educator, and associate professor at Università di Camerino - SAAD Ascoli Piceno. Luca was a founding member of the firm IaN+, a visiting professor at the Bartlett School of Architecture, Ecole Spéciale d’Architecture in Paris, and Confluence in Lyon. He obtained a Master's in Spatial Science at the International Space University, UHA. He is the author of several books. With Ian+, he received several prizes, including the Gold Medal for Italian Architecture in 2006. His research around architecture is made not just by architectural projects but through different research tools: two blogs (www.the-booklist.com and www.the-imagelist.com) and the collective of CAMPO www.campo.space. Co-Curator of the first Architecture Biennale in Orleans at the Frac Centre Ville de Loire Marcher dans le réve d'un autre (October-April 2017).

Michael Robinson Cohen is a founding member of Citygroup, a visiting lecturer at Bard College, and the author of the book Housing as Housing, published by Black Square. He earned an MPhil in Architecture and Urban Studies from the University of Cambridge, a Masters in Architecture from Yale, and a Bachelor of Arts from Brown University. His research at the University of Cambridge was funded by the Bass Scholarship in Architecture granted by the Yale School of Architecture. Before graduate school, he served as the Community Coordinator for the Hollygrove Design Initiative, a neighborhood-based design organization funded by the National Endowment for Arts. His work has been published in Burning Farm, Journal of Architecture, NYRA, AA Files, Pidgin, San Rocco, and Scroope.

Valerio Franzone is Managing Editor at KoozArch. He is a Ph.D. architect (IUAV Venezia) and the director of the architectural design and research studio OCHAP | Office for Cohabitation Processes. OCHAP focuses on the built environment and the relationships between natural and artificial systems, investigating architecture’s role, limits, and potential to explore possible cohabitation typologies and strategies at multiple scales. Valerio teaches design studios at The School of Public Architecture - Michael Graves College at Kean University. He has been a founding partner of 2A+P and 2A+P Architettura. His projects have been awarded in international competitions and shown in several exhibitions, such as the International Architecture Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia. His projects and texts appear in magazines like Domus, Abitare, Volume, and AD Architectural Design.

Notes

1 Dialogue Not Monologue (Citygroup, New York, ongoing)

2 The Supreme Achievement - Twelve plaster rooms for twelve ideal cities (Campo, Rome, September 12 – October 3, 2015)

3 Misunderstandings. On the collection of Le Frac Centre d’Orleans (Campo, Rome, November 25, 2016 – January 13, 2017)

4 Geo-Fantasies: A Space Race on Planet Earth, by Andrea Molina Cuadro, co-curated with Reem M. Yassin (Citygroup, New York, April 19 – June 16, 2024)

5 Margaret Kohn, Radical Space: Building the House of the People (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003).

6 Campo, Zibaldone (Rome: Veii, 2024)

7 Aperture (Fondazione Pastificio Cerere, Rome, January 31 – March 15, 2025)