What does ‘architectural thinking’ look like when it comes from a child? How soon is too soon to introduce ideas like multidisciplinarity, world-building and spatial agency? Elena Karpilova and Alexander Novikov of The Architectural School of Thinking for Children are building a powerful think-tank — with a cohort too young to buy a fishing licence. From a summer school in Minsk, to a community hub in Lisbon and soon to a pavilion in Venice, its founders say the children are our future.

This interview is part of KoozArch’s Issue #03 | New Rules for School.

KOOZ Thanks for making time for this conversation. May we go backwards, and then forwards? Or perhaps, let’s start with where you are now —

ALEXANDER NOVIKOV We started The Architectural Thinking School for Children in 2016 in Belarus, and moved to Portugal — where we are now — about two years ago. But we can say a few words about how we got here. We have been in Lisbon since May 2022, but our journey here was not so easy.

Before 2020, we had a kind of peaceful revolution in Belarus. For more than 30 years, we’ve had a sort of soft dictatorship: people move and work freely, but in each election, the same candidate wins. In 2020, a new generation — our generation — started to voice their support for another candidate, and although the regime didn’t allow for democratic forces to play out. People started to leave for fear of repression.

Then the war started between Russia and Ukraine — that was the final push for us, and we decided to leave too. In early March 2022, we fled to Uzbekistan — which was the only place we could go without a visa, and it was relatively safe. We felt that we were in a lot of danger during the first days of the war, when the government was starting to talk about militarisation — that would mean fighting against Ukraine, which we love so much. We spent one month in Kyrgyzstan: a crazy trip, in crazy times.

ELENA KARPILOVA We stayed in contact with the parents of our students — 70% of whom had also left Belarus. Online teaching was not a viable option, as we were all on the move without the necessary resources of stability — so we had to pause. Suddenly we received an invitation from the Lisbon Triennale of Architecture: they offered us help with our legalisation here in Portugal, using a building and supported us a lot in different ways. Quite simply, that’s how we moved to Portugal. We got here in May, and restarted our school in June 2022!

At first our Belarusian community helped us a lot, as some others migrated here too, as well as some private supporters. We restarted our school with a summer programme, free of charge for students from Ukraine, Belarus and Russia. And that's how we got going here — now we’re looking to expand our networks from the Lisbon Triennale to the Centro Cultural de Bélem; we hope to get to know more local organisations too.

KOOZ Let’s rewind back to when you started up in Minsk.

AN Well, I am an architect by profession; I studied in Minsk, then worked in Moscow and studied at Strelka, under Rem Koolhaas. Finally, I became a partner of an architectural studio with my father, back in Minsk. We were designing a huge bank at the time, and I realised that although we could design lots of beautiful, ambitious things, we could never build this building in Belarus — not the way we would like. We are only designers; then you have clients, construction workers, government departments, laws, bribery and corruption. In the end, regardless of the excellence of design, the result is not great.

I came to understand that if you want to do something good in architecture, you have to gather people who understand and share your ideas, which did not seem possible at the time. I had the opportunity to go elsewhere in Europe, but I really wanted to do something for my country. So I thought that if I can’t be this ambitious architect with ambitiously designed buildings, I will be an architect who designs education. So I started working with kids. At that moment, I had no idea how to do it but then I met Elina, who was really involved in working with young people. We began working together — I couldn’t do much without her, but gradually I found my own way to connect with the kids and in the end, I found that what we're doing together is much better than what I was doing as an architect. That’s my story.

"I thought that if I can’t be this ambitious architect with ambitiously designed buildings, I will be an architect who designs education."

- Alexander Novikov.

KOOZ So did you want to run an architecture school, or did you want to work with children?

AN I already had some experience of teaching adult students — students of architecture. Talking to them, it became clear to me that it was too late for the stuff I wanted to teach. I mean to say that the professional conception of these students is already set — you’re maybe working on a graduation project together, and there is no time to revise or include certain basic ideals and philosophies.

KOOZ I hear you: perhaps architecture school — and its students, who may be burdened with the aspirations of a career as well as with financial debt — is too far down the line to allow for a foundational, less professionalised approach towards architectural thinking. Elena, tell me your story.

EK I’ll add a few words. I'm not an architect at all. I was trained as a fine artist — classical oil-on-canvas, as if I lived in the 18th century! Eventually I studied comparative art criticism — a bit utopian, but it was lovely as we studied theatre, cinema, music. During this time, I had to earn money and so I started to teach. Throughout my studies and beyond, I had this really varied teaching practice: from young children in official public primary schools, to college applicants, even older ladies who wanted to learn about art history.But I wanted to do something for my people; I felt that I had something more to give back. And I had my own slightly traumatic experience of a very strict post-Soviet education, which was completely disconnected from the real world. For example, my conception of an artist was quite outdated.

Then too, I think I'm still a little child myself — I remember childhood as the best part of my life, and I remember all my emotions very clearly. I don’t know how, but I think I understand children intuitively — it's very special to work with them. When I met Alexander, I wanted to change something in education, but we decided early on to work in parallel to more formal education systems. One day we would want to share our experiences, through and with the support of other academies or institutions; the concern and focus of childrens’ education — and education in general, across ages — deserves to be elevated. For now though, I think it’s important to remain independent from official education.

KOOZ Right; you’re not trying to replace or compete with a system that has its own value and mode of operation. You're serving other needs that deserve recognition. So: you decided to establish a school. What prompted such a big step. and why architectural thinking — perhaps you could define that?

AN We started doing workshops together during the summer of 2016. At that point, with friends who were professional teachers. After a certain period we realised there was a lot of interest, and decided to make regular courses that run year round.

EK Actually, we didn't, and I think we still don't intend to have any proper architecture classes. After our 2016, parents started to follow up, asking us to please continue. We really felt this need from the parents, and a certain hunger in the city for what we were able to give.

AN On ‘architectural thinking’ — of course, I imagined an architectural school. But talking about it with Elena, she wondered if we really need another one — and I had to agree that we do not. In the end it led to this more complicated scheme, which I think is even better.

"The idea was to take the model of a regular architect who is using all these disciplines and knowledge to make only one project, and apply it to a school."

- Alexander Novikov.

Take an architect who is trained to do a lot of things: designing, researching, presenting. They must have a certain understanding of economics, political science, philosophy, art, anthropology — it’s a never-ending list, and it is not possible to excel in all spheres — but the more you understand, the better architect you usually make. The idea was to take the model of a regular architect who is using all these disciplines and knowledge to make only one project, and apply it to a school. A child moves from one discipline to another, culminating in a single project. For example if we run a semester of architecture, in order to design a building, they must go through lessons in contemporary art, in storytelling — as they would have to write a story about their project. They will learn how to make models, and even dance in order to understand form with their body.

EK We’re also running a semester of cinema, which is not so easy to explain to parents — where’s the architecture? At this point, we have to remind them we’re teaching architectural thinking — though the children might also go through classes of modelling, scenography, storytelling and history. And some disciplines are already interdisciplinary — like cinema or theatre. We’re also going to start a semester on the book — drawing on the idea, to quote Irma Boom, of a ‘book-architect’. Parents often insist that they want their children to become architects — and they can.But it’s not an architectural school — it's a school of thinking.

"But it’s not an architectural school — it's a school of thinking."

- Elena Karpilova.

KOOZ On your website, you say that you synthesise some of the best educational thinking from various countries, and also various architecture schools. Can you talk about this process of synthesis and where it started for you?

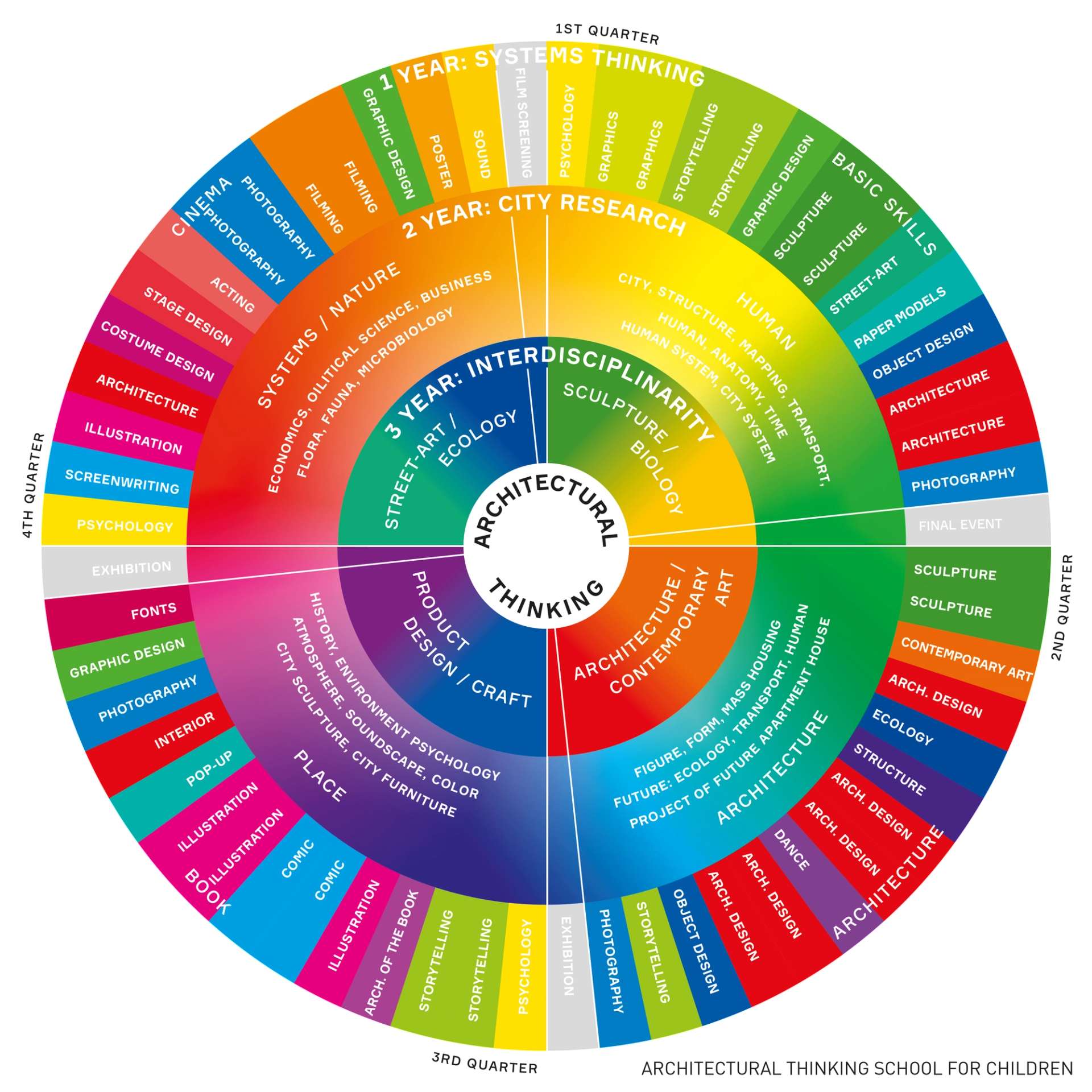

AN I think it stemmed from my earlier Soviet education. You might say that some things about it were outdated — it is very strict, very production-oriented — but at the same time, there are things that can be taken forward. Later, I studied at Strelka Institute in Moscow — I was a second year student when Rem Koolhaas was heavily involved with the school. Actually, Koolhaas would also compare architecture with cinema: it’s not about the container, but how the container frames the experience. Strelka itself was an educational experiment; when I was studying, it was still in a process of formation. Most of the students were from different backgrounds, countries and universities, yet we were all sharing this educational experience. That’s what I was drawing from.I should also say that if you notice some similarities to the multidisciplinary approach of the Bauhaus project, that was an inspiration for us — we hope to continue a tradition of pushing education forward. We’ve spent some time developing graphics and narratives to explain our approach, and we're really proud of our scheme.

Architectural Thinking School for Children, programme.

EK For my part, I studied in Paris for a few years including French language and culture — completely unconnected to architecture, yet in a way the process of learning, as well as the act of studying the construction of another language, did influence my thinking: our ideas are drawn from our experiences.

KOOZ The value and legitimacy of lived experience is starting to be recognised more widely, alongside formal qualifications and pedagogical theory — synthesising various experiences, including those of colleagues, peers and students. But the process of translating architectural processes or these complex ways of looking to your age group — six to fourteen — seems like it could fill a book by itself.

"[Children] can pose very simple questions, but at the same time, very tricky ones. Like, what is architecture? Try to explain it to yourself at seven years old, with all the complexity of knowledge that you have."

- Elena Karpilova.

EK Yes, actually, we’d love to make a book about it. You can invite an expert, a star in their field, but it's hard work to show them how to teach children. They need a vocabulary that is absolutely different. And in my opinion, it's much more difficult to explain something to children: you need to understand your subject fully, but also how to explain it in simple words. It’s similar to that multiplicity of architectural thinking: you need to understand a bit of psychology and to be a little bit of a show man or woman; to be a good manager, thinking about time — and also, to remain a little childlike yourself.

Try to imagine you're seven years old again. What were your thoughts? How did you talk? What did you think about? People often forget what childhood was like. A seven year old child is someone who, just a few years ago, started to go to the bathroom by themself. They can pose very simple questions, but at the same time, very tricky ones. Like, what is architecture? Try to explain it to yourself at seven years old, with all the complexity of knowledge that you have. it takes time to learn how to do that. Sometimes people think they can teach immediately. We respect their knowledge and believe in their capacity, but we insist on training. In fact, training people is one of the hardest parts of our work, as currently we do everything by ourselves; that is running the school as well as the training, even while I’m keen to share our expertise.

KOOZ How important is this factor of not only linguistic but also cultural cohesion? Your students and tutors are all drawn from migrant communities from Eastern Europe; how does this commonality play out in the context of Lisbon?

AN When we moved from Belarus, our main idea of architectural thinking gained additional value, namely as a way of connecting communities. We're working only with migrant children, whose parents need community too. We are becoming a sort of an island here in Portugal. We're working with migrant students from Russia, Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, and Belarus, and most of our tutors are again migrants.

"We're working only with migrant children, whose parents need community too."

- Alexander Novikov.

EK In Belarus, our most valuable aspect was this notion of architectural thinking; people came to our school because of that. When we started up here in 2022, a lot of migrants had recently arrived in Portugal. We discovered that people were hoping to use the school as a network to find friends for their children, having moved to a new country. These children, when they join Portuguese schools, cannot understand the language; they might have lost their friends back in Belarus or Ukraine. So this is an instance where the school has helped the community to find each other, and our common background helps with that.

"When we started up here in 2022, a lot of migrants had recently arrived in Portugal. We discovered that people were hoping to use the school as a network to find friends for their children [...] the school has helped the community to find each other."

- Elena Karpilova.

On the other hand, we want so much to involve local practitioners and students, and actually we sometimes do invite youth volunteers — local teenagers — to help us during some lessons. Many of our students can speak some English, so they can communicate. This move in Portugal has changed our school; we reinvented and remade a lot, but we’ll need a little time to understand our context before we work with local children and connect with programmes in Portugal.

KOOZ I think that's fundamental, to bond with your context and feel at home in it. But teaching in Belarus must be different from being in Lisbon, where you’re addressing children from various migratory contexts…

EK We have one (unofficial) rule at the school: we don't discuss which countries students are from, in order not to trigger anyone. But... It's a very tricky question. If you had asked me a few years ago about whether our communities share a common background, most people would have agreed: yes, we’re all Slavic peoples. But it would have an absolutely different reaction from different communities today — like Ukrainians. I mean, you can understand that. We are all Slavic, but for now everyone is so divided.

I think it's a tragedy, because we are really very close to each other — we have so much in common, from costumes to histories. So… it's a tough question. I think that over the years, we will split more; actually now I can see how different we Belarusians are from Russians; Russians from Ukrainians; Ukrainians from Belarusians and so on. I think it's a tough but very important time for Eastern European countries, in terms of confronting the formation of identity. People need to know their roots and stories.

KOOZ Thank you for speaking to that difficult point.. It’s always hard to negotiate these conversations, especially in an educational context. So why is it important to introduce architectural thinking at a young age? And what do you want for the school in the next five years?

EK Well, architectural thinking; I’ll just say that when we began to research to find our name, we never came across the term “architectural thinking” in other schools, even across a few languages. More recently, we see it is used by some organisations and people out there, and we’re very happy about it, because it means it’s alive.

"What is important for us to connect children to the broader world, to and equip them with knowledge and skills that are useful today. We change our programme almost every year; we revise and modify, responding to changing concerns."

- Alexander Novikov.

AN When we started, our main ambition was to help kids who are going to regular schools in their awareness and engagement with the contemporary, globalised world; the standard education felt outdated, and very focused on the immediate context of Belarus. The idea was to sort of connect young people to a wider world. We thought that idea might change since we moved but to be honest, it hasn’t. State education, even in advanced schools, cannot change as quickly as we do. What is important for us to connect children to the broader world, to and equip them with knowledge and skills that are useful today. We change our programme almost every year; we revise and modify, responding to changing concerns.

EK Via this understanding of ‘architectural thinking’, we study some things with kids that even adults don't consider. But another important point for us is to give space to the childrens’ voices and for their expression. We tell our parents that this isn’t just a fun hobby to do at the weekend — we discuss things that are serious for the children; for adults, it’s valuable to listen to their opinions about the world — what they think about it, how they analyse it. Children do that, even at seven years old. One of our agendas is to give voice to children, and Alex can tell you more about this through our plans for Venice.

"It's important for us is to give space to the childrens’ voices and for their expression. It’s valuable to listen to their opinions about the world — what they think about it, how they analyse it."

- Elena Karpilova.

Classes in Lisbon, 2023. Photo: Architectural Thinking School for Children.

AN It is a serious question, and I'm going to respond seriously. In the end, what school teaches is basic stuff: one plus one for arithmetic; writing and reading; in history, there was Napoleon and so on. But what can you actually do with that? This is a big question for me.

I think the model of an architect gives you an opportunity — even as a kid — to start thinking about how you can change the world, how you can act. All our modes of thinking include a process of research, decision making, design and proposal of your solution for the world.Maybe you cannot fulfil it properly in the end — but you know how to do that; you can construct a plan for action. I think this is a very important idea for our school: if we have set up an institution, it’s not just Elena, myself and the other tutors, but rather like a think tank which works together — developing ideas together. This leads me to the Venice project, which I’d really like to explain.

In short, we’re working on a presence at the forthcoming Venice Biennale of Art — the theme of which is ‘Foreigners Everywhere’. How about that? It seems specifically designed for our school — working with migrants, foreigners, refugees — we just couldn’t miss the chance to reflect on this topic.

"I think the model of an architect gives you an opportunity — even as a kid — to start thinking about how you can change the world, how you can act."

- Alexander Novikov.

Our project is called Bambini Ovunque — children everywhere. This project is being undertaken by kids and people from migrant and refugee backgrounds together with us. We are searching, in a way, for a language that can be understood by any foreigners, and we decided on the intuitive language of games. We researched the subject for a long time — looking at historic or traditional and contemporary games, and in the end, we came up with our own. Once you work with kids, you learn that games are not simply something to enjoy; there are sometimes very precise and wise things to learn hidden in them.

For example — and it is a strange and frightening example — when we have our breaks at the Architectural Thinking School, we often observe children playing games that have nothing to do with our curriculum. One of the most popular is called OMON — which is the name of the special military service in Belarus, known for arresting protesters. It’s an adaptation of a very old game, of course, but now they call it OMON; one group is the police and the others are on the run.

KOOZ Right; it’s a timeless game of tag, but they're applying their present world-view to those dynamics. That hits pretty hard.

EK So we take the game — this act of play — as a universal language between people of any age, or nationalities. And as Alexander said, we do work with children who, now in Portugal, are foreigners. As adults, though, let's understand each other somehow. Let's try to understand through games: you don’t need language, you don't even need to say a word. But we can exchange and interact. Games are a great example of how people can live together.

"We take the game — this act of play — as a universal language between people of any age, or nationalities."

- Elena Karpilova.

KOOZ I can’t wait to speak to you again about what we learn from your work in Venice. So many interesting ideas and so much admiration for your work — thanks so much for your time.

AN & EK Thank you very much!

Bio

Elena Karpilova is an art critic, designer, curator, head and co-founder of the Architectural Thinking School for Children. Graduated from the Minsk State Art College named after A. Glebov with a degree in "Painter, teacher", Belarusian State University of Culture and Arts with a degree in Comparative Art. Founder of the Minsk Design Week, curator of projects and expositions in Belarus, Poland, Lithuania, Russia, France. Founder and owner of the KARPILOVA jewellery brand.

Alexander Novikov is an architect, head and co-founder of the Architectural Thinking School, partner at KARAKO Architectural Workshop. Graduated from Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design and the Belarusian National Technical University. Worked at TOTAN Architectural Workshop, ADM Architects, ABD Architects, member of the Union of Architects of Russia.

Shumi Bose is chief editor at KoozArch. She is an educator, curator and editor in the field of architecture and architectural history. Shumi is a Senior Lecturer in architectural history at Central Saint Martins and also teaches at the Royal College of Art, the Architectural Association and the School of Architecture at Syracuse University in London. She has curated widely, including exhibitions at the Venice Biennale of Architecture, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal Institute of British Architects. In 2020 she founded Holdspace, a digital platform for extracurricular discussions in architectural education, and currently serves as trustee for the Architecture Foundation.