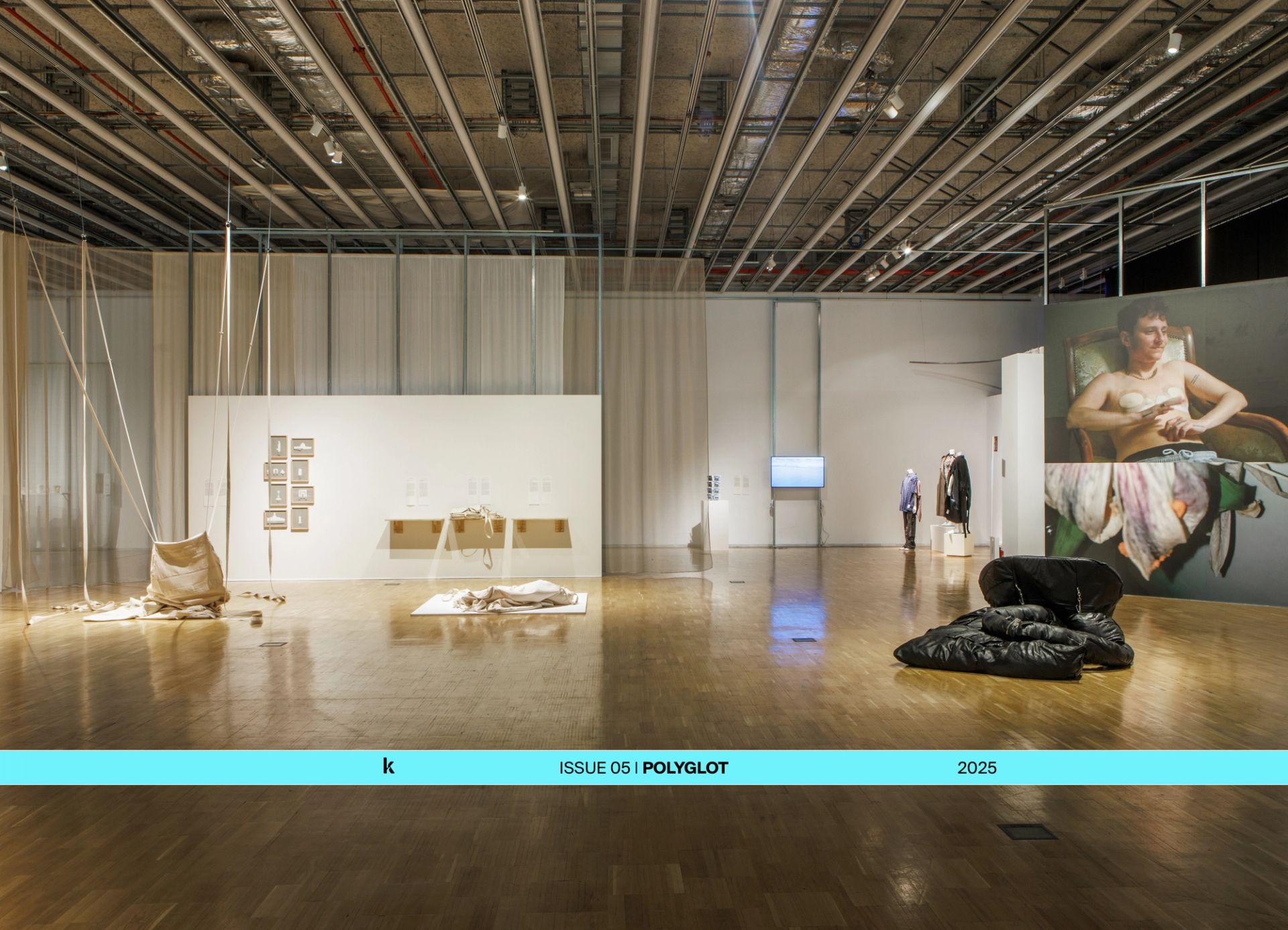

The recent edition of the Timișoara-based Beta biennial — curated by Oana Stănescu — wove together a rainbow of multidisciplinary practitioners and dreamers. The medium of film acted as a thread recurring through many critical installations and events. In this conversation, participants Jack Hogan, Nida Ekenel and Laurian Ghinițoiu discuss their contributions.

FEDERICA ZAMBELETTI / KOOZARCH cover me softly features a number of films, either as commissioned pieces,pre-existing works or as part of a curated selection of lecture recordings from Harvard GSD. How does film shape your perception of our built environment?

OANA STĂNESCUBecause of the power of the medium, film was important from the get go in conceiving the exhibition. To answer your question, maybe the most startling experience understanding the film's role in the perception of space was the first time I set foot in New York City. The first subway ride from JFK airport is a (nondescript) frame that is stored in my memory, along with the stupefaction at its familiarity. How could this giant city, in a different continent, feel so familiar to someone coming from another corner of the world? I never sought this city before in explicit terms, but a combination of its presence in movies and music videos made the body feel weirdly at home. Film has the ability to immerse us into space but also convey additional dimensions to other media through which we typically try to make sense of the built environment, such as drawings or photography. And because we receive so much of the world today through film — in various ways, whether it's tiktok reels or continuous news coverage — there is a feedback loop, a back-and-forth, a continuity, an exchange of information between the built environment and film.

"Because we receive so much of the world today through film, there is a feedback loop, a back-and-forth, a continuity, an exchange of information between the built environment and film."

- Oana Stănescu

JACK HOGANI explore the built environment through film, constantly recording videos of my everyday life. Buildings are always already shaped by cultures of representation: they inform how we view and make film; in turn, film informs how we make buildings.

NIDA EKENEL That's a difficult question. Instead of an answer, perhaps I will offer this passage from a novel I admire, The Loiterer* by Yusuf Atılgan:

"... A short-lived creature exists in our time, unknown to past centuries. A person who has just stepped out of the cinema. The movie he saw did something to him … It is hoped he will do great things. But he dies in five or ten minutes. The street is full of people who have not left the cinema; with their sullen faces, indifference, and sly walks, they surround and vanish him..."

KOOZ All of your practices explore film as a curatorial tool. Could you expand on the potential of this medium for you?

JHI think of film — video art, in particular — as a basin for other media, including sound, music, writing, animation, drawing, performance, painting, sculpture, personal archive and footage. That's what keeps me coming back to it, because I like to do a lot of different things and it’s satisfying to be able to edit and compile things sequentially when there aren't many occasions to do so spatially.

NEI can speak to the potential of this medium for my work at the Timișoara Biennial. My video — which I submitted through an open call — emerged from a realisation that a century ago, in 1923, Le Corbusier’s Vers Une Architecture (translated as ‘Towards a New Architecture,’) gained popularity partly because it included the word 'new' in its title. In the hundred years since, architects have laid claim to novelty, time after time. A New Lecture: Architecture's Century-Long Quest for Novelty, traces the long and tired history of this fetish. It montages publicly accessible lectures by prominent architects in their pronunciation of the word “new”; “new form of sensibility,” “new possibilities to make connections,” “together into a new, a new kind of hybridity…” and so on and so forth.

In addition to montaging, my video employs cropping and zooming from film to refine the clips into a series of physical gestures, accompanied by their corresponding sounds. I like to think that this focused mise-en-scène seeks to highlight the discrepancy between words and actions. Through the video, this pretense paradoxically becomes the very thing that unites these architects — who otherwise claim to share little common ground.

"If you truly know how to observe, things will naturally reveal themselves, and the tools I work with often emerge organically through this process."

- Laurian Ghinițoiu

LAURIAN GHINIȚOIU Until a few years ago, I worked exclusively with photography as my main tool to document the built environment. This project began in the same way — but from the very first day in the quarry, I felt overwhelmed by the power of the space; I realised it needed sound and moving images to convey its essence fully.

When I am curious about something, I usually follow my intuition, trying to impose as little as possible on the subject, allowing the work to reveal itself through presence and honest observation. If you truly know how to observe, things will naturally reveal themselves, and the tools I work with often emerge organically through this process. Presenting the film as an installation— rather than screening it in a cinema for a film festival — was an interesting and new experience. It felt more democratic, as people could choose when to enter and for how long to engage with it. It became a dialogue — an ongoing cut of frames in real-time. I was deeply surprised to see people standing for 47 minutes, completely absorbed by the work. At the same time, there are plenty of those who simply passed by without a glance.

KOOZ A New Lecture synthesises over one hundred lectures bypractising architects as a means of examining the profession’s obsessions with novelty. How far and wide does this obsession extend — and how is this reflective of the wider context within which architecture inserts itself? Where does that leave newness today?

NEFull disclosure: I’ve long shared the profession’s obsession with novelty. I, too, am an architect guilty of this pursuit. Over time, this evolved into frustration every time I heard someone else claim it. The video became no less of a means to confront and release this agitation.

In the study of these lectures, I discovered the pursuit of novelty ranges. There is the 'new' as the antonym of old, that belongs to the simpler world of dualities. Then there is the 'new' associated with prosperity, quality, and progress; synonyms crafted by modernity. We cannot reject the existence of an architecture that erects itself for merely claiming to be new. It allures an audience, that its use every so often becomes a good marketing strategy. There is the 'new' that assumes tabula rasa; by erasing existing contexts it claims to be brand new. And there is the ‘new’ as a filler word, a handy adjective to be used carelessly, as if its positive connotation could do no harm.

For some, each repetition of the word 'new' in the video renews a sense of comfort. For others, like me, it feels darker. It exhausts me. There is an irony of when the word “new” is frequented, even used twice; it diminishes itself with overuse. Immediately after the next takes precedence, it undermines its earlier claims. On a loop, especially, it prevents any notion of 'new' from ever truly succeeding. I feel that the video reveals how ambiguous and fleeting the concept of 'new' really is; it questions whether it can ever truly emerge.

One series of scenes stands out to me in particular: Sou Fujimoto’s lectures at the GSD, where he emphasizes 'new' while the word Veritas — Latin for 'truth' — remains visible on the lectern. As other clips take over, Veritas gets blurry and blurrier. While I didn’t intentionally focus on GSD lectures, I suspect this reflects a subconscious misfit I felt during my time at the institution.

"'A New Lecture' reveals how ambiguous and fleeting the concept of 'new' really is; it questions whether it can ever truly emerge."

- Nika Ekenel

KOOZ Your film v e i n s — as part of the installation Marble Journey — reveals the extraction of thirty thousand tons of marble from a quarry to create the shiny, translucent façade of the Perelman Performing Arts Center, situated at the World Trade Center site in Manhattan. What can sustainability mean in the context of buildings which have punched enormous holes in geological time and space?

LGThank you. As a documentary, ‘v e i n s’ aims to raise awareness by carefully unfolding that process, attending to every detail with almost obsessive precision, while also embracing a poetic approach that fosters emotional resonance and reflection on the need to harmonise human actions with the natural world. Nature, with its inherent emotional intelligence, operates in balance, efficiency, and without waste, managing resources with deep wisdom. Through its meticulous documentation, the film makes this process more accessible to viewers, offering crucial knowledge that deepens our understanding of the journey behind materials like marble. This understanding is vital for cultivating empathy toward Earth’s resources and the lives impacted by their use. It also challenges how architects or clients may overlook the broader implications of a seemingly simple request — such as “I want marble here” — advocating for a more informed, conscious approach to material selection. The film encourages a deeper appreciation for materials and a design ethos that mirrors the natural intelligence inherent in the materials themselves.

KOOZ Beyond the environmental impact of such constructions, the film dwells on socio-political contexts, geographical landscapes, working conditions, language barriers, energy consumption and capitalist influences. What is the capacity of the filmic medium to unearth these narratives?

LGThe film uses the medium’s unique capacity for juxtaposition; by contrasting elements such as rhythm — rapid sequences versus still, almost motionless scenes — it mirrors the tension between the relentless pace of industrial production and the timeless, contemplative qualities of nature. Similarly, the interplay between micro and macro scales, from close-ups of hands performing repetitive tasks to sweeping wide shots of natural landscapes, reveals the human labour and environmental toll embedded within these processes.

The cultural and socio-political contexts emerge subtly through geographic and territorial shifts during the pandemic. Scenes of food, ethnicity, behaviour, and language convey a sense of place, while the lack of subtitles challenges viewers to experience these differences intuitively, emphasising both the universality and specificity of the human experience. The informality of certain production steps contrasts sharply with the precision and rigour in others, reflecting disparities in working conditions and the uneven impacts of global capitalism across regions. Graphics also play a critical role in bridging these narratives, highlighting the marble’s journey through locations and the distances travelled. This visualisation underscores the energy consumption and logistical complexities of transporting such materials, pointing to the larger capitalist systems driving these processes. As the kilometres decrease, the accompanying sound evolves into a concert, echoing the transformation of raw material into a refined product and suggesting the increasing strain and intensity as the marble nears its destination.

The dualities present throughout the film — such as the split screens during Zoom calls — highlight contradictions: the world of architects, the fathers of the architectural buildings versus the raw physicality of labourers, the craftspeople and their lifestyles and the moral weight of beauty created at a cost. In these contrasts I invite viewers to reflect on the socio-political and ethical implications of their choices, urging a deeper awareness of the interconnected systems at play. Although everything is presented as dualities, they may eventually create a balance. A balance that puts the film in a neutral pace, one where the viewer is empowered to decide on their own.

"I invite viewers to reflect on the socio-political and ethical implications of their choices, urging a deeper awareness of the interconnected systems at play."

- Laurian Ghinițoiu

KOOZCows and Flies explores the nature of maps as a form of control and categorisation. What brought you to Skowhegan, Maine to engage with the eight cows featured in the video? How did the act of ‘covering’ enable a more truthful relationship with the other?

JH I was invited to a nine-week artist residency in Skowhegan, Maine in the summer of 2019 — and these cows happened to live on the same 350-acre campus as the artists.

I got up each day at dawn, when they were huddled together, snoozing. The herd’s sleepy entanglement looked like a knot. I admired their indifference to me. I wondered what it would mean to live in a more-than-human community, more equally shared. One of my clearest televisual memories from childhood in Ireland is of cattle being destroyed during the 1996 Mad Cow crisis. In Rwanda, for example, cows have a totally different relationship to humans. There, they play a part in shaping culture and society.

I started making masks and then full costumes for my visits to the cows because I read that they don’t like direct eye contact. You could see some of these in the small photographs hung on the stove in the installation. On my last week in Maine, I made a life-size print of the cows (which also floated overhead in the cover me softly installation). It served as a cover for a group of humans to perform, as well as a map of the herd at a moment in time. Cowhides already resemble maps, and so I was reminded of the Borges and Carroll stories that also feature in the video, about one-to-one scale maps, that is those maps that would be large enough to cover their original site.

‘And then came the grandest idea of all! We actually made a map of the country on the scale of a mile to the mile!’

‘Have you used it much?’ I enquired.

‘It has never been spread out, yet,’ said Mein Herr: ‘the farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country and shut out the sunlight! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well.’”

— ‘Sylvie and Bruno Concluded’ by Lewis Carroll (1889)

The resulting video, “Cows and Flies”, traces lines between imposed individuation and mapmaking, in the broadest sense of flattening and establishing or contesting boundaries—how rich social lives and shared places are fragmented and stripped of information, context and complexity, in order to be instrumentalized, branded and easily consumed. We are encouraged to pluck out one aspect of ourselves and the other, and present this as the meaningful whole, eclipsing or denying the other parts for the sake of externally imposed definition.

Maps are covers. They are objects of political and social world-making, from wars to vacations. Maps usually depict the oblate spheroid earth, or other three-dimensional objects, on a flat plane. Implicit in these translations are decisions that determine priorities. Misrepresentations exist at every scale; Europeans, in particular, frequently used ink to draw lines that did not exist in reality. Drawing perimeters is an invasive procedure, an imperial attempt to regulate and contain differentiation. It is meant to exclude and make a boundary around generativity and degeneration. The creator reserves the right to transgress.

Various devices, motifs and perspectives weave together to form a video tapestry. My text and drawings combine with aerial and handheld footage, the sound of animals with the buzz of the drone, voices and silence. The drone is technology that is largely used for extraction. Its lens looks down from the heavens, conveying an air of neutrality. It flattens and alienates, making everything landscape, much like a mapmaker. I tried to shift that perspective to understand this operation and de-abstract those surveilled and surveyed by it.

“'Cows and Flies,' traces lines between imposed individuation and mapmaking, in the broadest sense of flattening and establishing or contesting boundaries."

- Jack Hogan

KOOZ All of the works were exhibited within the context of cover me softly. What is implied or offered by the notion of the cover as a means of looking forward?

NEI think A New Lecture responds to this exciting curatorial theme in two ways. First, it quite literally 'covers' multiple lectures, bringing them together into a single composition. This aligns with the open call, although, I presume, compositionally, A New Lecture would be a cover in the mode of a mash-up. Second, the theme of 'cover' questions the very notion that I sought to explore: novelty. A cover, by default, acknowledges that it builds upon something, rather than assuming a tabula rasa. I believe this interplay between the idea and the means strengthens the work.

Additionally, the video connects with the audience at one of the oldest buildings in Timișoara. Hearing architects summon novelty within narrow adobe-covered masonry walls with flaking paint adds another layer of contrast. I couldn’t attend the biennial, but from the photos, I was pleasantly surprised by this subtle touch from the exhibition team. Once I recover from this one, I am looking forward to making another cover of A New Lecture: Architecture's Century-Long Quest for Novelty.

LGBy recognising the tension between surface appearances and deeper layers, we can better understand how to move forward — embracing vulnerability, striving for authenticity or reconciling who we are with how we want to be perceived. Layers act as covers: sometimes for protection, and sometimes as a way to belong or be accepted. These covers can be strategic, aesthetic or even symbolic, shaped by trends, ego or the desire to use a specific language or behaviour to fit in.

Understanding these covers requires patience and neutrality — avoiding the urge to immediately define or judge a situation from our perspective, instead considering the perspective of others. It also involves exploring the space between the cover and the reality that lies beneath, acknowledging the duality of two realities: the “in and the out,” the “here and there,” the “before and after.” When we examine the emotional or financial costs of maintaining these layers, we can assess whether they serve a meaningful purpose or hinder authenticity. Authenticity, after all, is often a source of truth and that which is genuine. By thoughtfully engaging with these covers — whether to critique, embrace, or challenge them — we create opportunities to foster genuine connections, informed decisions and a shared sense of purpose.

Bios

Nida Ekenel is an architect. She enjoys engaging with salt and paper, musing upon novelty and potatoes, and dismantling the air-conditioners and electrical sockets. She has been published in MIT Thresholds, UCLA Pool, and The Funambulist, and was featured at the Royal Scottish Academy Annual Exhibition in 2024. You can also find her contributions at the 2023 Harvard Arts First Festival, the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale, and the 4th Istanbul Design Biennial. Nida holds a Master of Architecture from Harvard Graduate School of Design and a Bachelor of Architecture from Istanbul Technical University, with international studies in Lisbon and Tokyo.

Laurian Ghinitoiu is an artist that unearths the stories of the people and processes embedded within the built environment. Using photography, videography, objects and installations to blur the line between space, architecture, art, and image, his work critically explores the connections between architecture and its larger socio-economic contexts. What began as a curiosity for Ghinițoiu soon turned into a way of life taking him on a continuous journey around the world. Nomad for several years, this way of observing helps him understand the complexity of the built environment in the global context. Spontaneous meetings are the starting points of a series of ongoing conversations, books and exhibitions.

Jack Hogan is an interdisciplinary artist and architect from Waterford, Ireland. Their work focuses on the rich sociality of everyday life, foregrounding friendship and what constitutes good shared lives and places.

Oana Stănescu completed her architectural studies în Timișoara, working internationally before establishing her studio in New York and Berlin. She is also a co-founder of the collaborative project Plus Pool in New York. Through her projects, Stănescu encourages us to rethink our relationship with the built environment and explore the possibilities of creating urban spaces that prioritise livability and sustainability. Most recently, she established the interdisciplinary Blueprints of Justice Studio at MIT in collaboration with the Stanford Legal Design Lab and Virgil Abloh. In 2023, she established and started curating the “Nonprofessionals” lecture Series at EPFL in Lausanne.

Federica Zambeletti is the founder and managing director of KoozArch. She is an architect, researcher and digital curator whose interests lie at the intersection between art, architecture and regenerative practices. In 2015 Federica founded KoozArch with the ambition of creating a space where to research, explore and discuss architecture beyond the limits of its built form. Prior to dedicating her full attention to KoozArch, Federica collaborated with the architecture studio and non-profit agency for change UNA/UNLESS working on numerous cultural projects and the research of "Antarctic Resolution". Federica is an Architectural Association School of Architecture in London alumni.