Both the recent book Histories of Ecological Design - An Unfinished Cyclopedia (Actar, 2024) by Lydia Kallipoliti and the agenda of The Emilio Ambasz Institute for the Joint Study of the Built and the Natural Environment directed by Carson Chan extend from ongoing investigations into the relationships between architecture, the environment, science and politics. Such histories contribute to establishing various roles for architects, as researchers, educators or practitioners who can participate in possible reworlding, addressing not only the environment but also issues of equity and justice.

VALERIO FRANZONE (KOOZ) As we approach the climatic tipping points1 and their catastrophic social, political, and economic consequences, you have both worked to reorganise the history of relationships between design and the environment. What are your projects’ founding urgencies, ambitions, and methodologies?Are they also a way to reorganize criticism of the ecological design?

LYDIA KALLIPOLITI (LK) It was not really my intention to write a total history of ecological design. In fact, I find writing an encyclopaedia a very threatening task — I have always considered it dubious to hold an idea of encircling knowledge and writing a definitive, singular, history. Histories of Ecological Design started many years ago, when the Oxford English Encyclopedia of Environmental Science asked me to write a peer-reviewed text of the history of ecological design. Although I originally hesitated, I took on this rather daunting challenge.

In the end, it was a beautiful, if painful project, which allowed me to see that in architecture and design circles, ‘ecological design’ is a very recent term. It was only in 1996 that Sim van der Ryn and Stuart Cowan used the term in their book, Ecological Design.2 But the term ecology was coined in 1866 by Ernst Haeckel. Interestingly, both definitions — made150 years apart — establish ideas of harmony and balance. It was really about a sense of integration of organisms and structures with the natural environment; a seamless continuum that unfolds, say, between buildings as objects and their environment. This is the main way that the term has been used. There's a pervasive idea in design — one which has infiltrated economic institutions and political constructs — that any designed object should synchronise with the natural world; even that there is such a thing as an untouched and purely natural world. One of the things that I have been trying to argue is that ecology starts from the moment designers reproduce natural systems synthetically. Also, that the world can be understood as a system of flows, rather than a compilation of objects.

"One of the things that I have been trying to argue is that ecology starts from the moment designers reproduce natural systems synthetically."

- Lydia Kallipoliti

The other fundamental critique is that ecological design, from the outset, is a deeply rooted, extractive, colonial project. It originates from the long exploratory journeys of white European men, journeys that exemplify their physical endurance and fortitude, and overlap with the noble scope to document the world’s living stock. Despite this disclaimer, the book does not offer alternative indigenous histories; rather, it reassesses the values entrenched in the various perceptions of ecological design asan ideological instrument and didactic structure.

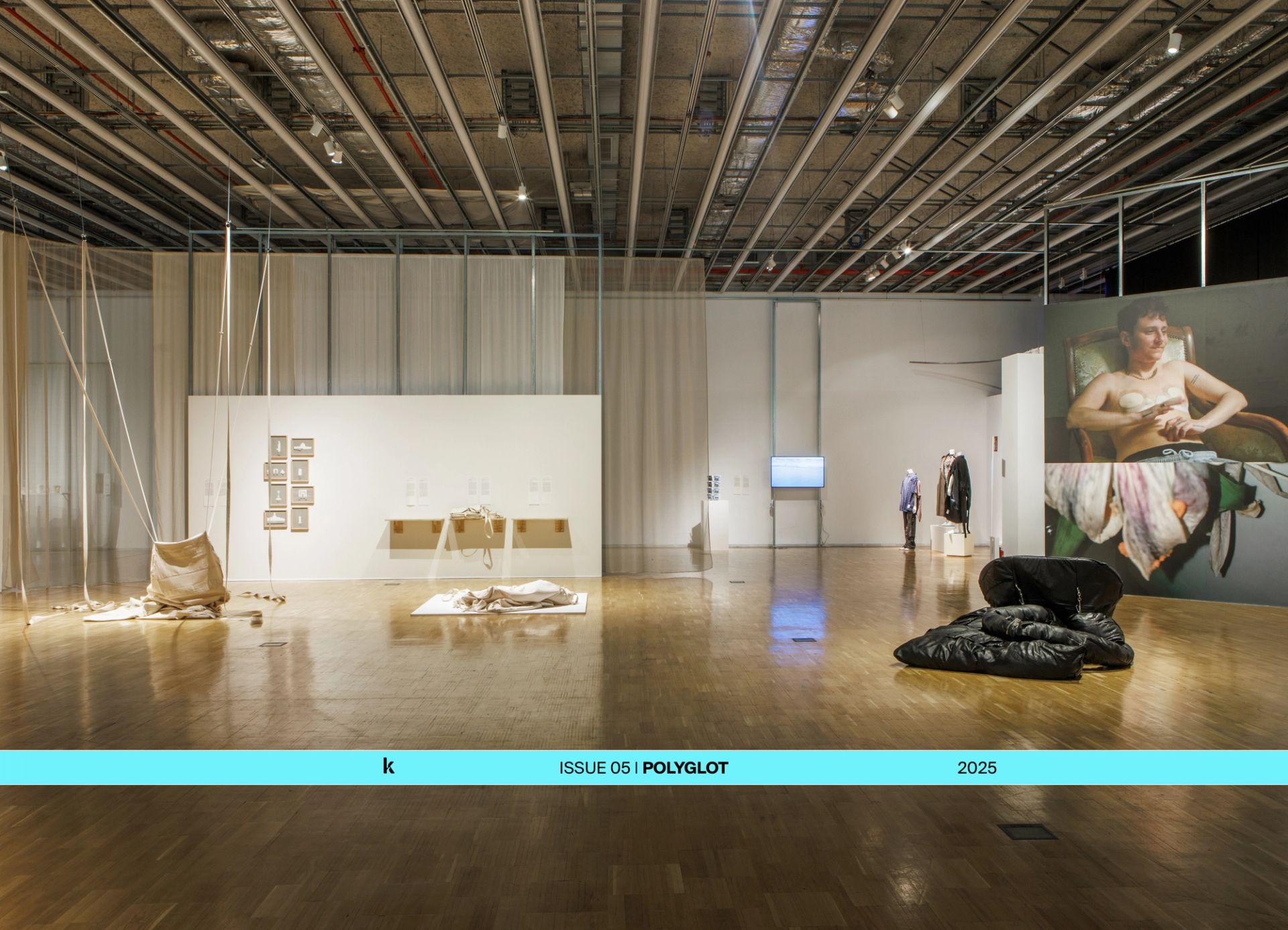

CARSON CHAN (CC) Many things between our two projects rhyme. The Ambasz Institute’s first exhibition, Emerging Ecologies,3 and the two accompanying publications4 were all framed through the mission of the Institute, which is to redefine architecture as process, not as object, as it is traditionally understood. By seeing architecture solely as buildings, we miss the many different histories that are crucial in accounting for the ways humanity has adapted its surroundings to its needs: architecture is a process that includes everything from resource extraction, the labour connected to that extraction, and the social, political, economic, and racial context in which buildings are produced. It also includes the afterlife of buildings because what happens when we're done with them is crucial: do we dismantle or demolish them? The building is just a particular moment of the architectural process. The lens of environment and ecology compels us to redefine architecture and its history differently. The exhibition starts in the 1930s with Frank Lloyd Wright and ends in the mid-1990s with the advent of LEED certification. This period covers modern architecture but presents projects constituting nodes of a new, retroactively formed movement we called environmental architecture.

"Architecture is a process that includes everything from resource extraction, the labour connected to that extraction, and the social, political, economic, and racial context in which buildings are produced."

- Carson Chan

Interestingly, while we gravitated towards environmental architecture, Lydia uses ecological design in her book. I find the term environment to be more expansive. In the 50s in the US, environment meant surroundings and context — encompassing not only the “natural” but also cultural, social, or technological surroundings. Harvard had a program in Environmental Design, started in 1953 by Serge Chermayeff, about structuring neighbourhoods through cars, privacy and belonging, but not really through ecology. In the 60s and 70s, “environment” took on an ecological dimension. Finally, by the late 90s or early 2000s, we associate “climate” with the environment. I was drawn to how the term environment can continually shift and how it has modified architecture in the process.

KOOZ Design cannot be about controlling the environment but about understanding architecture's role, limits, and potential to comprehend how to cohabit with nature. To do that, we need to change our operative approach. I recently talked with Philippe Rahm about how 'Architectural Design' and 'Building Physics' should be integrated instead of being two separate disciplines. Looking back in history, how could we reshape the discipline and professional practice to address this issue?

CC We can do this in many ways, it’s just about being strategic in choosing where to put pressure. The conventions of professional practice are currently acting as a bottleneck to progress even though new engineering and construction the technologies are there, ready to be used. Part of the problem has to do with habit. For example, making a mass timber building requires relearning how to design and build, changing a cascading number of workflows, including new certifications, material specifications, and licensing. It is an expensive process. Even if the architect wants to make these changes, does the client?

In the academic setting, however, students are demanding to learn about the climate crisis and environmental issues. Change is starting on the pedagogical front. Part of what I'm doing at MoMA is understanding that we're not policymakers. I work at an institute of public education to help change the conversation so that we can be prepared for the future; we have programmes to address pedagogicalpractice. For example, one is a discussion series called Architecture Studio in the Anthropocene, where we invite studio coordinators of all architecture schools in the United States and Canada — about 350 architecture schools — to join in conversation with design instructors who have been integrating climatic and environmental issues into their studios. We run this to impress upon academic coordinators why and how addressing the climate crisis in schools is urgently necessary. Change in professional practice starts at school, and connecting practice with education is fundamental.

LK I found it poignant that Carson's exhibition stopped chronologically at the development of LEED and other comparative sustainability criteria. This moment marks a critical shift in environmental history. With the dissemination of the term “sustainability” — most broadly quoted from the United Nations Brundtland Commission in 1987 — as well as the institutionalisation of design policies, mostly promoting mainstream corporate values, there was a very particular shift to the epistemic dimension of metrics and measurement. This transition has created an enormous schism between the agency of how architects think, draw, and design, versus how they can assign value to the success of these forms relative to environmental concerns.

"Only through pathologising materials, techniques, processes, and life cycles, can ecological design regain merit and relevance."

- Lydia Kallipoliti

For example, many understand environmental practices as different systems that are added to an existing formal structure, like adding apparatuses to make buildings sustainable and performative. Yet, it is critical to consider how environmental problems and questions may generate new languages of space and representation. Metric assets (like the carbon footprint) need to be addressed not only as tools of technical classification, but also as social, political, and conceptual constructs that can be reshaped through a reform of values. Only through pathologising materials, techniques, processes, and life cycles, can ecological design regain merit and relevance.

Another vital aspect of integrating these ideas in contemporary practice is understanding the dimension of physical bodies as part of spaces: they sweat, leak, cry and shit. All these things make them active ingredients in the formation and transformation of environments; understanding these interactions between climate and bodies is fundamental, not just as abstract phenomena but as embodied experiences.

CC To continue Lydia’s discourse regarding response to the profession, thinking through the environment allows us to understand that architecture is already an environmental discipline. If you look at architecture before the industrialisation and globalisation of building components, things were built with local climate and materials in mind; there was necessarily a built-in understanding of climate. I think we should distinguish between building designers and architects. An architect can think through and incorporate the social, climatic, material, economic, and racial systems in a structure; a building designer does not.

KOOZ Did you find architects applying this environmentally driven holistic approach to professional practice?

CC What's interesting about Emerging Ecologies is that we never considered it a celebration of practices. The show included projects that I don’t think were great ideas, projects that failed, and projects that didn’t develop in ways their creators intended. Emerging Ecologies is an incomplete survey of US architecture’s response to environmentalism, and the rise of environmental activism in the US, like Lydia’s book, is an incomplete cyclopedia of projects responsive to climate questions.

LK In the third part of the book, I present many contemporary practices but as Carson says, it's not about celebrating the practices as much as identifying the conceptual and theoretical threads or worldviews aligning these designers. In many ways, they offer new ways to think about the discipline.

CC Precisely, but I must add that the failures I highlighted in the exhibition are also incredibly instructive. We decided to make a historical show as the first Ambasz Institute exhibition a historical show because it is necessary to revisit the mistakes of the past in order to avoid reproducing them; hopefully the historical works on display can provided the basis for future critiques of architectural culture and discipline.

KOOZ Lydia, in the book, you question the economy several times; you say that “the history of ecological design is a deeply rooted, extractive, colonial project,” and you mention the performance issue of sustainable design, which is tied to capitalism by transforming sustainability into a commodity for real estate and public funding. Operating within the framework of capitalism —for example, there are efforts to make certifications for BIPOC or women-owned businesses producing mass timber to diversify the ownership of the wood industry— can ecological design shift the relationship between economy and environment?

LK I wish I had the answer for this, because I am yearning for and seeking a viable answer. The economic dimension is critical as the whole project of sustainability, from the nineties onward, has shrouded capitalist economies under a thousand veils of environmentalism and attendant ethical claims. Replacing ecological design with sustainable design offered up the narrative of performance, the spectacle of the numerical, and the value of technical expertise as the prime constituents of success. This turn, an aspect of capitalism, has promoted illegible frameworks and a type of bureaucratisation that generates its own experts while preventing the general public from partaking in the caring and co-evolution of the world. Nevertheless, the creation of technical subsets of criteria for sustainability are infused with paradoxes and absurdities that are difficult to reverse: for example, glazed facades that diminish thermal loss and thus reduce energy bills, also contribute to the development of the sick building syndrome.It's a complicated problem deeply ingrained in market values, commodities, and economics, and we don't have control over those things as designers.

Ideologically, I am completely aligned with decarbonisation and non-extractive architecture, but I don’t know if there's a realistic path forward to counter economic realities, except through small counter-actions that may become conceptually representative of alternative futures. The agency of designers to create small subversions is pivotal and critical; it’s within the responsibility of environmental literacy and what we teach.

KOOZ Absolutely, we need to celebrate these subversions in order to change the general mindset. Michael Braungart and William McDonough’s book Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things,5 which you mentioned, is also about changing our approach.

LK That book was instrumental to me, but I admit to having a love-hate relationship with it. I love many of the ideas — in fact Cradle to Cradlelargely motivated me to write my previous book, The Architecture of Closed Worlds,6 — exploring the possibilities and faults of circularity. But I hate the way in which ideas are promoted as an institutionalised common-sense for architectural production. In the book, the design agency is reduced to a series of canons, often resulting in questionable architecture. Nowhere in the book is there any path forward as to how circular systems and thinking might apply to architecture and design as a discipline with its language, syntax, tectonics, and intelligence.

CC I'm thinking about how architecture and the building sector can change capitalism. Architects require proximity to power and capital to build; buildings, especially in the global North, are manifestations of capitalist systems, so I don't know if architects have the agency to change capitalism. Still, we can operate with some of the tools of capitalism to change the system itself; indeed, certifications have a role. I'm also thinking about how trends work in commodity culture. For example, veganism has become very trendy, which is great for the environment, even if people might not care that meat production is a huge contributor to climate change. I wonder if clients and architects even need to care about the environment in order for sustainability in the building sector to succeed. Maybe we need to create a condition where environmentally friendly actions are “on trend,” desirable, and can be effective.

Think about it through materiality: we can have a conventional building, or a sustainable one that looks the same but costs twice as much; no one will want that. However, if we produce an aesthetic of sustainability, in which people can express their positions, perhaps that could make a difference. So, can we use the logic of style and design to promote and serve sustainable goals? In our transition phase from carbon to non-carbon-intensive, we should try everything.

KOOZ Carson, your exhibition shows how environmental activism is linked to fights against racial, cultural and social inequality. The double-direction causal link between ecological crises and these issues is clear. How should design be connected to these struggles to be more environmentally efficient?

CC We presented the Yavapai Indians opposing the plan to build the Orme Dam on their land in Arizona. Preventing something from being built is as much an architectural project as building something. The environmental justice movement has galvanised through these protests and consequently changed the built environment through policy and the introduction of regulations. It enacted material changes at a scale that people who draw buildings will never address. You don't need to be an architect to change the built environment. The sooner we realise that the discourse of architecture includes a lot more people than those trained in architecture schools, the sooner we can use the discipline to make it effective as a voice in the urgent conversation about the climate crisis. It also allowed us to insist on indigenous primacy in American architecture, especially when it comes to the environment. Ecological knowledge of this land has existed for millennia in the native communities that have been killed or displaced.

"Preventing something from being built is as much an architectural project as building something."

- Carson Chan

LK Architecture is a fundamentally political act; it cannot be devoid of a political position. Any decision we make — this is very much related to the distinction Carson makes between the architect and the building designer— is not just about creating forms but a logic of life patterns where livelihood circulates. Rather, it is enabled or disabled through different spaces, their connections and interactions. One of my favourite examples to speak about environmental politics is the train that carries shit from New York City to Alabama. The shit train devalues real estate because of the smell and methane clouds, which are also explosive; it lands in Alabama to further impoverish the land of poor communities. The devalued territory where unwanted waste is deposited is no accident. Waste is deposited precisely at places where people do not have the economic and political power to protest or reverse these decisions. So, creating infrastructures that reuse human waste on-site could be a solution. Not allowing or diminishing garbage or waste exports out of metropolitan environments is not just a question of design; it’s a question of equity and justice, a demonstration of what environmental inequality is all about. Protesting against these phenomena is not an act of design, but design logic may lead to reversing such outcomes, and this is what we should be doing in the discipline.

"The sooner we realise that the discourse of architecture includes a lot more people than those trained in architecture schools, the sooner we can use the discipline to make it effective."

- Carson Chan

KOOZ Our understanding of design, what it addresses, and how — for example, systems and processes — is linked to how we represent projects. Similarly, it is how we communicate architecture to the public. How has ecological design changed the paradigms of architectural representation?

LK Architecture representation has been enormously immune to change since the Renaissance, excluding the representation of environmental phenomena, which is a huge problem. Since the 1960s, Howard Odum's Energese or “Energy Systems Language” has instrumentalised ecosystems, as well as human agency, in terms of input and output. This representational language for ecological simulation models, derivative from electronic circuits, has become the primary tool for architects to visualise performance and energy flow. These deductive forms of representation have become the main way to illustrate environmental phenomena through a series of arrows, symbols and diagrams, which differ substantially from pictorial representations of flows, such as what we now call computational fluid dynamics. The plague is that the arrow — which is not an architectural symbol — is the only symbol we use to convey these phenomena in drawings; it reduces everything to a linear causality, even if these physical phenomena are more complicated and need different languages. The language of environmental representation is fundamental because the aesthetic dimension of environmental issues has vacillated enormously. There is no formal language that is related to the way we represent physical interactions. We must change that, and in this sense, I side with Philippe Rahm. We must know how to describe physical phenomena and complexities.

CC The exhibition demonstrates architecture’s struggles with representation with many examples, like Howard T. Fisher’s invention of an early computational mapmaking system, Ian McHarg and his students’ giant, hand-coloured maps of the Delaware River Basin, and Beverly Willis’s bespoke digital design program CARLA (Computerized Approach to Residential Land Analysis). Still, I agree with Lydia that architectural representation has not evolved much. We should differentiate the discourse: if in professional practice we need to hold on to the plan, section, and elevation as construction drawings, in architecture education, there’s no need for that because there are many media to express architecture beyond drawings, like film, narrative, and audio. Today, we have many options.

KOOZ Lydia, you are a professor and received a Ph.D. while Carson, you are currently pursuing a doctorate. I am interested in how pedagogy at all levels is changing or should change in response to the ecological crisis.

CC At MoMa, we engage with children on topics like the climate crisis in the hopes of reaching the next generation of policymakers. With our Learning and Engagement team, we transformed many works in Emerging Ecologies into activities for students from kindergarten to grade 12. We distributed them to more than 5000 schools in the New York area. We've been organising field trips for teachers that equip them to give their students environmental literacy. Soon, we hope to make children's books and videos to introduce kids to sustainability concepts like the circular economy. So, in a generation or two, children who grew up on these books will think it's ridiculous that we use a plastic cup for five minutes and then bury it underground for 500 years. This way, my work can help to change the conversation.

"The dynamics of ecology is not hierarchical but inter-relational, co-constitutive, horizontal. Should this change the way we even think about scholarship itself?"

- Carson Chan

Thinking through ecology and the environment compels a different method of scholarship, especially at the PhD level. In Western academia, we work through archives, books, and field research — all very structured forms of knowledge. In contrast, the dynamics of ecology is not hierarchical but inter-relational, co-constitutive, horizontal. Should this change the way we even think about scholarship itself? Are books inherently better than oral histories? Is academic writing more truthful than poetry? These become fundamental questions once we accept ecology as the entire condition in which all life is embedded on this planet. Last year, we started experimenting in this way with Building Life: Spatial Politics, Science, and Environmental Epistemes,7 a two-day symposium organised by Spyros Papapetros and Esther Choi on the relationship between the built environment and nature. They invited people from different disciplines, and this approach permits the analysis of one topic through many different lenses. There were architecture historians, poets, literary scholars, historians of medicine, for example. It is a way of seeing scholarship ecologically because it changes the hierarchy between various modes of thinking.

"Mediation and abstraction via statistics, cautionary tales, and daily practices of scarcity are not possible in our age of planetary disruption."

- Lydia Kallipoliti

LK At the Cooper Union, I teach every year a course called “Environments”, which specifically provides undergraduate students with a conceptual grounding in environmental issues; I also teach electives on environmental technology, environmental history and theory along with thesis studies. I would argue that throughout these courses, a main objective is to face climate change as an embodied and lived experience as it lands on human and non-human bodies, as physical entities experiencing the world.Mediation and abstraction via statistics, cautionary tales, and daily practices of scarcity are not possible in our age of planetary disruption. Indicators of climate change — greenhouse gas concentrations, rise in sea levels, ocean heat and acidification — are more than numbers. They are literally embedded in bodies and demonstrate how environments manifest themselves. Bodies are co-produced by and with the environment; they are not passive organisms inserted in a given, built, and measured context.

A second matter which is critical is that climate change registers not only in the flesh and chemical constitution of bodies, but also in the severe displacement of populations, climate migrations, and territorial inequalities. The need to mitigate and confront it as a matter of justice and equity.

KOOZ One last question about the relationship between architecture and the environment: where is the field of ecological design or environmental architecture going, and where should it go?

CC I'll answer it by saying that, hopefully, all architecture will be environmental architecture. I would like to see the fields of building design, architecture, and the building sector move towards and assimilate environmental architecture’s energy, dynamics, and ambitions. It is a fundamental understanding that any human act on this planet is an environmental act. The sooner we realise this, the sooner we recognise that any destruction we do destroys our ability to live.

LK At this moment, we must ask more of architecture beyond the scope of shaping the experiential aptitude and design of the physical world. Amidst current interrelated crises — namely the climate emergency, social inequity and war — the role of pedagogical institutions and educational curricula is critical to reform, rebuilding renewed alliances and hierarchies with real impact. At this vital moment, architecture as a practice of knowledge must constantly re-situate its productive capacities, and interrogate how it gets its power, economy, materials and labour, as well as to understand the present and future role and operational capacities of buildings in urban and exurban environments.

Bio

Lydia Kallipoliti is an architect, engineer, and scholar whose research focuses on the intersections of architecture, technology and environmental politics. She is an Associate Professor at the Cooper Union in New York. Kallipoliti is the author of The Architecture of Closed Worlds, Or, What is the Power of Shit (Lars Muller Publishers, 2018), the History of Ecological Design for Oxford English Encyclopedia of Environmental Science (2018) and the editor of EcoRedux, an issue of Architectural Design in 2010. Her work has been awarded, published and exhibited widely including the Venice Biennial, the Istanbul Design Biennial, the Shenzhen Biennial, the Oslo Architecture Triennale, the Onassis Cultural Center, the Lisbon Triennale, the Royal Academy of British Architects, the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York and the London Design Museum. She is the principal of ANAcycle research thinktank, which has been named a leading innovator in sustainable design in Build’s 2019 and 2020 awards and Head Co-Curator of the 2022 Tallinn Architecture Biennale that was the winning project of the year at 2023 Design Educates Awards. Kallipoliti holds a Diploma in Architecture and Engineering from AUTh in Greece, a Master of Science (SMArchS) from MIT and a PhD from Princeton University.

Carson Chan is the inaugural Director of the Emilio Ambasz Institute for the Joint Study of the Built and Natural Environment and a Curator in the MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design. He develops, leads, and implements the Ambasz Institute’s manifold research initiatives through various programs, including exhibitions, public lectures, conferences, seminars, and publications. In 2006, he cofounded PROGRAM, a project space and residency program in Berlin that tested the disciplinary boundaries of architecture through exhibition-making. Chan co-curated the 4th Marrakech Biennale in 2012; in 2013, he served as Executive Curator of the Biennial of the Americas in Denver. His doctoral research at Princeton University tracks the architecture of public aquariums in the postwar United States against the rise of environmentalism as a social and intellectual movement. He is a founding editor of Current: Collective for Architecture History and Environment, an online publishing and research platform that foregrounds the environment in the study of architecture history.

Valerio Franzone is the Managing Editor at KoozArch. He is a Ph.D. Architect (Università IUAV di Venezia), and his work focuses on the relationships between architecture, humanity, and nature, investigating architecture’s role, limits, and potential to explore new typologies and strategies. A founding partner of 2A+P and 2A+P Architettura, he later established Valerio Franzone Architect and OCHAP | Office for Cohabitation Processes. His projects have been awarded in international competitions and shown in several exhibitions, such as the 7th, 11th, and 14th International Architecture Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia. His projects and texts appear in magazines such as Domus, A10, Abitare, Volume, and AD Architectural Design.

Notes

1 Betsy Reed, “Earth on verge of five catastrophic climate tipping points, scientists warn”, The Guardian (December 5, 2023)

2 Sim Van der Ryn, Stuart Cowan, Ecological Design (Washington DC: Island Press, 1996)

3 Emerging Ecologies - Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2023-2024)

4 Carson Chan, Matthew Wagstaffe, Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2023);

Counter Ecologies, eds. Carson Chan, Eva Lavranou, Matthew Wagstaffe, Dewi Tan, Art Papers, Issue 47 no. 1, Fall 2023.

5 William McDonough, Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things (Berkeley: North Point Press, 2002)

6 Lydia Kallipoliti, The Architecture of Closed Worlds, Or, What is the Power of Shit (Baden: Lars Müller Publishers, 2018).

7 Building Life: Spatial Politics, Science, and Environmental Epistemes: November 10, 2023, Princeton University School of Architecture, Betts Auditorium; November 11, 2023, The Museum of Modern Art, Bartos Theater [online]