Presenting the little-known history of the Turkish-speaking community in Yugoslavia, the exhibition Translated Into Socialism explores how a Turkish identity was affirmed and transformed under multinational socialist ideology. In this conversation, curators from SALT Galata in Istanbul explain the historic and spatio-political context of the exhibition.

This conversation is part of KoozArch's issue "Polyglot".

KOOZ Let’s start from the roots of the exhibition ‘Translated into Socialism’ – which traces back to 1920, to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and in particular to the Turkish-speaking community in Kosovo and Macedonia. Could you share some context for the lesser-known history of this community and its involvement in the formation of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia?

CURATORIAL TEAM The experience of the Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and the First World War (1914-1918) were crucial conflicts for the Turkish-speaking community in Yugoslavia. Before these wars, Kosovo and Macedonia were part of the Ottoman Empire. The wars left a devastated population, traumatised by war, epidemics and migration. The newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes promised democratisation, including agrarian reform. However, people soon realised this promise was empty, specifically in Kosovo and Macedonia. At that time, the region of the Kingdom including Kosovo and Macedonia was called ‘South Serbia’ and was subject to an even more oppressive regime than other parts of the country. The agrarian reform was used as a political tool to Slavicise. Serbian culture was promoted; the Albanian language, for instance, was not allowed in public institutions. Many people emigrated after the war, though others stayed. Most of the wealthy Muslim landlords and citizens who remained in the Kingdom were able to reclaim their properties. They even collaborated with the Belgrade regime and were used as a buffer against the radicalisation of poor Muslims toward communist ideas. Despite this, many Muslims followed communism and sought salvation in internationalism. In this atmosphere, many Turkish-speaking people from Skopje, Prizren, Prishtina, Bitola and other parts, supported the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. They protested against the Kingdom’s regime and saw the Russian Revolution as a political inspiration for a democratic future in the Balkans.

"The project aims to highlight the overlooked history of the Turkish-speaking community in Yugoslavia between 1920 and 1980 and how actors of this period initiated a unique perspective that is based on internationalism and solidarity."

KOOZ By looking into the lesser-known narratives of the Yugoslavian Turkish speaking community, what kind of alternative histories does the exhibitions reveal? What is the value of doing so today, within a cultural space like SALT?

CT The project aims to highlight the overlooked history of the Turkish-speaking community in Yugoslavia between 1920 and 1980 and how actors of this period initiated a unique perspective that is based on internationalism and solidarity. However, the other important aspect for us is to challenge the etho-nationalist discourse and narrative that is so prevalent in the world today. We aimed to highlight an alternative history of national formation in a politically progressive and multinational country. What should be done with the nation and national minorities in a context where capitalism is challenged by a new socialist reality? How can we rethink the relationship between nationalism and socialism? What kind of shifts do these new relations create in the language of a community? How could national formation occur in an internationalist context? These are some of the questions the exhibition sought to explore in this rich and little-known history. These questions still remain relevant to our present.

Coming back to your question about SALT; we have been working with archives through exhibitions, workshops, and public programs since its opening in 2011. The Lumbardhi Foundation, one of the collaborators of the exhibition, has also been working in partnership with us for some time — so we thought that Salt Galata was the most appropriate venue for the exhibition.

KOOZ The exhibition draws our attention to pedagogy and the spaces and forms it can inhabit: from the library of the Great Madrasa or school of King Alexander I in Skopje, to the prisons of Yugoslavia. What role did these places play throughout the resistance? What other spaces proved pivotal for the mobilisation of Yugoslavian Leftist Organisations?

CT The history of Yugoslav communists before the Partisan War is also a history of imprisonment, torture and migration. The Party (CPY) was banned in 1921 by the Kingdom, and its archives were burned. Many people were either killed, tortured, imprisoned, or forced to migrate. The situation, with its ups and downs, continued until the victory of the Partisans. The students of the Great Madrasa present an interesting case in Skopje. The school was opened in the early 1920s by the Kingdom in order to 'enlighten' and contain the Muslim population in Kosovo and Macedonia. Contrary to the regime's plans, the school became a hub for communists, where discussions, secret readings and protests were organised. Many students took part in the Partisan movements, and many of them were also imprisoned and killed. Since there were numerous communists in the prisons during the 1930s, it also became an underground place where discussions and translations of Marxist literature took place. Hayrettin Volkan, a young Turkish activist of the CPY at that time, was also imprisoned in the early years of the Partisan War. Later, he included his prison memories in his books Gül Goncasi and Kanlı Sabahın Baharları. These are exhibited at the exhibition. One could read these books to gain a better understanding of prison life and solidarity among communists at that time.

"We aimed to highlight an alternative history of national formation in a politically progressive and multinational country. What should be done with the nation and national minorities in a context where capitalism is challenged by a new socialist reality?"

KOOZ Specifically, ‘Translated into Socialism’ unearths and reworks historical materials — sourced from private archives and public libraries – in the form of newspapers, propaganda posters, poems and books (for both adults and children). How were these literary documents pivotal in mobilising the anti-fascist resistance?

CT The materials included at the Great Madrasa were crucial for the partisan struggle. The first Turkish-language newspaper, Birlik, was also published at the end of 1944, just after the liberation of Skopje. The rest of the printed materials either date from an earlier period or from the socialist construction of the country. Especially notable are the materials from the early period of Socialist Yugoslavia, which are being exhibited for the first time.

KOOZ What role did women play in the process?

CT The role of women in the anti-fascist resistance is extensive. For example, The Women’s Anti-Fascist Front (AFŽ), which was formed in 1944 and lasted until 1953, was organised in different parts of Yugoslavia by volunteer women. We are focusing on the Macedonia and Kosovo branch in the exhibition, which was never thoroughly studied. During the liberation struggle, they concentrated on communist pedagogy and literacy courses in a context where more than 80 percent of women were illiterate. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Macedonian Front published its own Turkish-language journal, Yeni Kadın [New Woman], in Skopje. The organisation was also active in negotiating and implementing the unveiling campaigns. Apart from AFŽ, there are individuals like Nakiye Bayram; as a teacher, she is considered one of the leading figures in the history of Macedonian modernisation. Also Kevser Seyfullah, who was active in education, campaigns and various other anti-fascist activities.

KOOZ How does the exhibition and research project approach the role and importance of language in shaping identities?

CT The real national formation of the Turkish community in Yugoslavia occurred after the partisan revolution. The Turkish language was supported through public schools, publications, television, radio, and other media. The language encountered the basic challenge of appropriating the socialist literature and terminology from scratch. It didn’t have an established tradition to rely on. During the formative years of the socialist state, if there was any such tradition in the Turkish language for the Yugoslavs, it was probably Nazım Hikmet. As a result, new terminologies had to be created. As the exhibition title suggests, the language had to be translated into socialism. This process led to a shift in the language and played a significant role in the formation of the cultural identity. The exhibition, in a way, tries to visualise this shift.

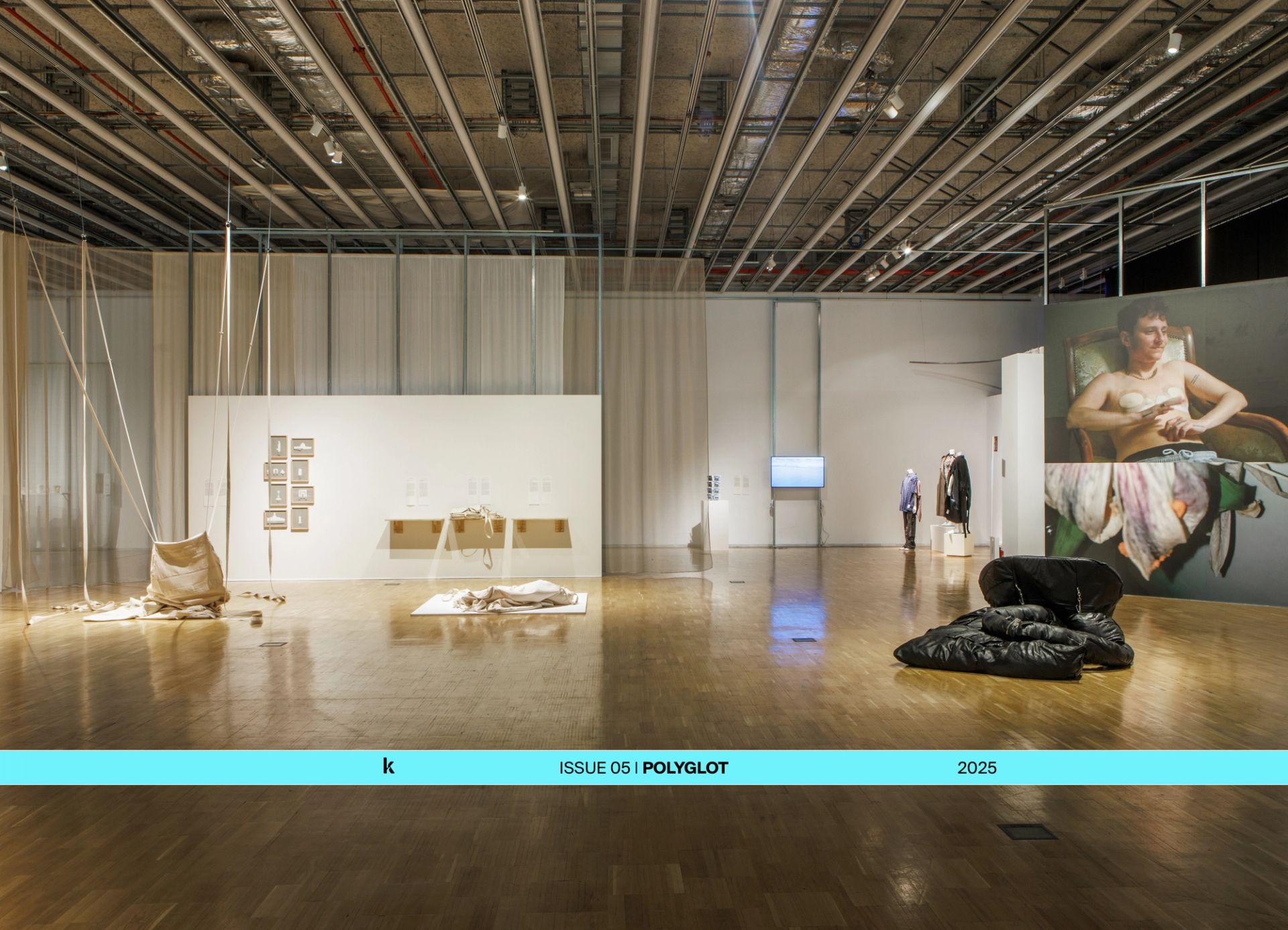

KOOZ Throughout the exhibition historical materials are juxtaposed to contemporary works by artists Mustafa Emin Büyükcoşkun, Yane Calovski and Hana Miletić (amongst others). How do these occur spatially within the venue? What kind of new dialogues and conversations do these juxtapositions seek to establish?

CT We have invited five artists to the exhibition: Mustafa Emin Büyükcoşkun, Yane Calovski, Hana Miletić, Ahmet Öğüt, Fevzi Tüfekçi and Dilek Winchester. Their works in the exhibition respond to the historical materials and open up new research and subject scopes, almost like 'further readings.' We have invited these artists quite early in the process. We had time to discuss the scope of the exhibition together; they are familiar with each and every archive document. For the layout of the show, all of us decided early on to intertwine the archival presentation and the works. This means that the archives and the works are actually presented together in the space; the boundaries between the documents and the works are marked by abstract lines.

Bios

Translated into Socialism is programmed by Sezgin Boynik, Tevfik Rada, and Merve Elveren and realized in collaboration with the Lumbardhi Foundation (Kosovo).

Sezgin Boynik is a writer, editor and publisher based in Helsinki. He founded Rab-Rab Press, an independent publishing platform in Helsinki that combines experimental art and leftist politics with scholarly rigour and a punk attitude. He is a founding member of Pykë-Presje in Prizren, Kosovo, an independent space using archives to oppose the nation-state narratives.

Merve Elveren is a curator based in Istanbul. Between August 2011 and September 2018, Elveren was part of Research & Programs at SALT (Istanbul). Some of her projects realized at SALT include A Promised Exhibition — Gülsün Karamustafa (co-curated with Duygu Demir, 2013), How did we get here (2015), and Continuity Error — Aydan Murtezaoğlu and Bülent Şangar (2018). Elveren was the curator of the Guest Programme of the 39th EVA International-Ireland’s Biennial (2020-2021) titled Little did they know. In 2022, she co-curated In Time / On Ground in the 17th Istanbul Biennial. In 2023, the second iteration of the project was exhibited at the Archive (Berlin) in the In the Inner Bark of Trees exhibition. She is the co-editor of Cengiz Çekil: 21.08.1945-10.11.2015 published in 2020. Recently, she curated Translated into Socialism with the researchers Sezgin Boynik and Tevfik Rada at Salt Galata. In 2018 she was the recipient of the Independent Vision Award for Curatorial Achievement, awarded by Independent Curators International, New York.

Tevfik Rada is a sociologist based in Prizren. He is the co-founder of Pykë-Presje, a research and publishing platform focused on people’s movements and contemporary art. He is currently pursuing a PhD at Central European University in Vienna, where he is researching the socialist intellectual history of Albanians in Yugoslavia.

Federica Zambeletti is the founder and managing director of KoozArch. She is an architect, researcher and digital curator whose interests lie at the intersection between art, architecture and regenerative practices. In 2015 Federica founded KoozArch with the ambition of creating a space where to research, explore and discuss architecture beyond the limits of its built form. Prior to dedicating her full attention to KoozArch, Federica collaborated with the architecture studio and non-profit agency for change UNA/UNLESS working on numerous cultural projects and the research of "Antarctic Resolution". Federica is an Architectural Association School of Architecture in London alumni.