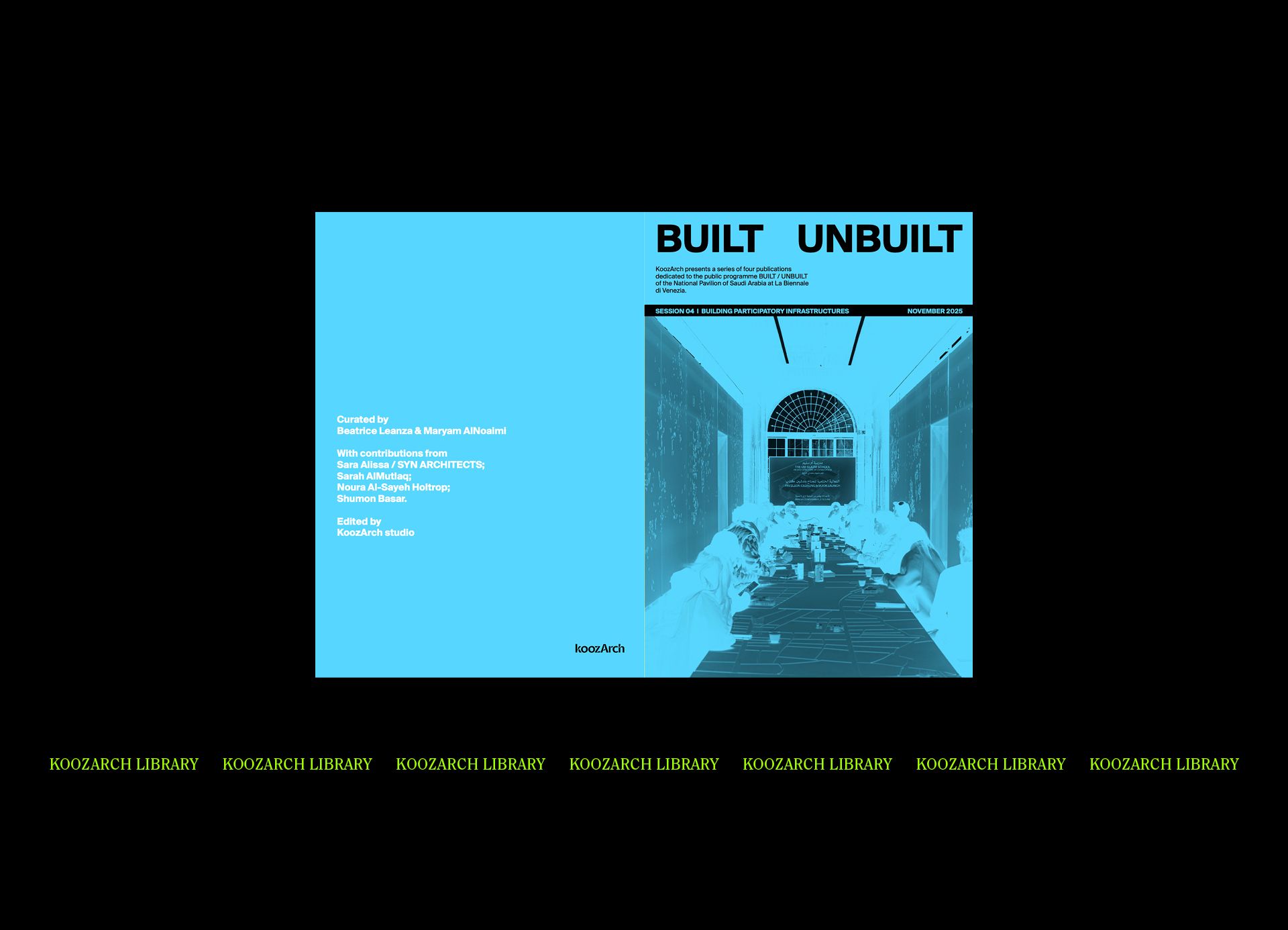

This is an excerpt from the BUILT / UNBUILT: Archiving Otherwise reader edited by KoozArch on occasion of the Public Programme accompanying the Pavilion of Saudi Arabia at the 19th International Architecture Exhibition which is available to download at this link.

Federica Zambeletti / KOOZ Could I ask you to start introducing your practice and how you approach this idea of pedagogies of proximity?

Yuri Tuma I apologise if some of what I share overlaps with what you may have already found in your research about us, but it’s important that you hear it directly from us — to listen not only to “what” you do but “how” you speak about it — because tone, voice, and the way we exchange ideas are just as meaningful as what’s written on a website.

I’ll briefly skip over two of our main areas — the curatorial and editorial components of our research platform — because I think the main reason we’re here today relates to our academic programming. That has really become one of the pillars of our work and one of the core ways we engage with others. Our academic activities began quite organically. Gabriel Alonso, one of the co-founders, was already deeply involved in seminars, knowledge-sharing, and collective thinking around the concept of ‘postnature’. When we came together to shape the Institute for Postnatural Studies, it was clear that this academic dimension — this space for exchange and learning — would be central to how we operate and how we want to connect with people.

When we decided to launch the Institute, we imagined it as a very physical, situated space — in Madrid. Our idea was to invite people in, to start the school in person, engaging directly with our community. That was the vision: imagery, presence, physicality.

Then 2020 hit; with it, our confinement in Madrid. Suddenly, we were faced with the question: what do we do now? How could we engage with the audience we had imagined being physically present with us? People who we thought would be right there, talking with us, sharing the space.

The launch itself was a little cringe-worthy. I remember wondering whether we had even gone live, because we had launched it on YouTube and we didn’t really know how to operate this new medium. Yet, in a way, this hybrid experiment became the foundation of our school: blending online and in-person experiences while constantly thinking about proximity. One of the things we’ve questioned is the assumption that being online means being separate. Why do we automatically treat “in-person” and “digital” as a binary? What we’ve learned is that presence is not just physical — there is always someone listening, even if cameras are off or circumstances vary. We are present together, regardless of the medium.

Time and separation have also become fascinating dimensions to explore. We’re lucky to engage with people all over the world, which introduces different time zones and experiences. Someone connecting from Australia at 4 AM experiences the session very differently from someone joining from Argentina at 4 PM; your body, your energy, even what you’ve just eaten, all shape how you engage. This interplay of proximity and time has become central to how we think about presence and connection.

KOOZ You mention that hybridity is central to the way you operate. Could you elaborate on the specific types of formats you’ve been experimenting with? Additionally, what kinds of communities or individuals do you engage with? How does your programming relate to courses offered within traditional academic spaces?

YT Some of the formats through which we’ve been engaging with our academic programme are seminars. These are short-term, typically lasting four to six weeks, with sessions held once a week online. The seminars cover a wide range of topics, and we invite researchers and thinkers exploring areas such as blue ecologies — oceans, rivers, glaciers — as well as other emerging ecological frameworks. We also explore intersections with vocational paths, opening up spaces for dialogue between researchers, artists, and thinkers, as well as students at various stages — undergraduates, graduates, postgraduates, and master’s students.

This has become a kind of ecosystem for our academic program. From our perspective, universities often lack engagement with contemporary ecological frameworks. While there are certainly excellent programs addressing these issues, the feedback we receive indicates that these conversations are still relatively rare. This is precisely why our space is so important — it fosters dialogue and thinking in ways that are otherwise largely absent in traditional academic settings.

KOOZ One of these seminars is the Postnatural Independent Program, could you expand on this further?

YT Yes, that is a six-month academic programme which is a truly hybrid format that we’ve been exploring, where most of our engagement happens online, but we also come together for two in-person encounters in Madrid. Those moments, when geographically separated bodies finally meet, are always incredibly exciting. Seeing and connecting in three dimensions, hearing voices without the mediation of a computer, experiencing the ambient energy — there’s something about that shift from virtual proximity to physical presence that is truly special. Zoom is an amazing technology, but it naturally filters the world in a particular way; these transitions are moments of reconnection that are both tangible and emotionally rich.

The Postnatural Independent Programme is structured around theoretical modules where participants share research on situated practices. We strongly believe in thinking together and learning from people deeply engaged in specific fields. In these modules, academic content is collectively explored, and we encourage participants to reflect on the balance between structure and freedom — verticalities and horizontalities that aren’t static, but can wobble, shift, or even disappear. This balance is crucial to creating a safe space.

We admire programs that embrace anarchic learning, where participants self-guide and explore freely. That approach is brave and inspiring, yet we’ve also found that mixing some guidance with this flexibility helps generate a sense of safety. Structure can sometimes be necessary — it doesn’t restrict freedom; it supports it.

Another core aspect of the programme is collective practice. For instance, participants contribute to an editorial project over six months, generating content for books. These projects are enriching, but they are also time-consuming and sometimes stressful. Managing that balance — between collective energy, production goals, and individual well-being — has been central to our understanding of safe space. That first edition of the programme was pivotal for us in critically thinking about what a safe space could be.

I love to share a particular moment from that first day: after months of preparation, curriculum design, and framework creation, we finally connected globally with the participants. We began with a sentence that reflects our Postnatural framework: “We should rethink our relationship with nature.” Immediately, someone raised their hand and asked, “Who’s we? Why are you speaking for me?” That single question became a lens through which we explored the entire six-month program:

- Who is “we”?

- What does it mean to be human, and in how many ways can we be?

- What defines a community — can it be ephemeral, malleable, inclusive, exclusive?

- Can non-human beings be part of this safe space?

These questions continue to drive our thinking about safe spaces and community.

Yuri Tuma presenting 'we?', a publication developed and edited within the framework of the Postnatural Independent Program 2023.

KOOZ It’s interesting that you connect this back to language. How have you been exploring language at the Institute and how does that tie into the research on safe spaces done for the pavilion?

Gabriel Alonso At the Institute we’ve been reflecting on the growing use of certain buzzwords that are now entering academic and pedagogical spaces — terms such as “safe space”. For the public programme at SAR, we wanted to propose a critical rethinking of what a “safe space” actually means when approached from an academic or institutional perspective. At the same time, we hoped to draw on the practices and experiences of the other practitioners present to reshape this concept. Perhaps a truly safe space may not even be possible — but through dialogue, through relationships, and through the ways we listen to one another, we might begin to create certain conditions or explore alternative methodologies that open up new forms of collective action, proximity, and relation.

When asked to reflect on pedagogies of proximity and relation, I found that particularly stimulating. Recently I have been thinking with other practitioners and philosophers about how ecological thought has introduced terms such as “entanglement”, “interconnectedness”, and “being together”. These words have become pervasive, evoking a kind of enchantment with the idea of constant interrelation among beings, thoughts, and ideas. I’ve been revisiting that notion critically, and what I’d like to propose is that we also consider the beauty and necessity of ecologies of distance — an approach that gives room for the other to exist and to have agency. In that sense, we’re exploring proximity through a process of critical revision.

I’m reminded of a beautiful conversation we once had with Karen Barad — a friend and quantum physicist — who said that if things actually touch each other, there would be no relation. Even atoms don’t truly touch; what connects them is the gap, the in-between. And perhaps it is precisely there, in that space of separation, that relation occurs.

This resonates strongly with the work we do at the Institute. When we speak of postnature or the postnatural, it is a critical invitation to think with the other — to think with those entities, beings, and forces that are not like us but that nonetheless constitute us. For us, the ‘postnatural’ serves as a framework for engaging with difference, for recognising how the heterogeneous and the unfamiliar co-create the cosmopolitical and ecological spaces we all inhabit and work within.

KOOZ Could you expand upon the work done with the students specifically focusing on the Safe Space workbook as well as this collection of practices presented within the exhibition at Palazzo Diedo?

Daniel H. Rey I joined the Saudi Pavilion project back in February when I went to Riyadh on behalf of IPS and started thinking of space spaces as being both situated and relational — a culture of relatability. Relatability, for us, emerges from proximity and shared engagement. In developing this concept, we recognised the importance of positioning the Global South at the forefront of discourse — not merely as a subject, but as an active agent shaping architectural knowledge.

In our work, we emphasised engagement in the process of inquiry rather than seeking predefined “safe spaces,” as no rubric existed at the outset. Reflecting on my own experience at the Institute of Arab Culture of Colombia, a mentor once described the concept of the ‘Arab Caribbean’ as a place everyone knows exists, even if its borders are undefined. This resonates with our approach: we have an intuitive sense of safety and belonging, but defining the material and spatial conditions that produce it requires exploration.

With the invaluable support of students and practitioners, we began identifying patterns and gestures within complex gestures — moments, configurations, and architectural forms where one might feel safe. This pattern recognition exercise allowed us not only to understand students’ experiences but also to contextualise architectural practice within specific temporal and cultural conditions — such as contemporary Saudi Arabian sites in 2025.

This approach highlights the broader mission of the Institute: to operate not as a conventional centre of knowledge replicating existing power structures, but as a slow, deliberate centre of trans-local, cross-cultural exchange. Our work in Riyadh, for example, prompted us to ask: how do we engage meaningfully with local residents, regional histories, and national contexts — without imposing familiar narratives from distant capitals?

Ultimately, our aim is to craft architectures of presence and safety that are both locally grounded and globally resonant, allowing spaces to emerge through attentive, relational practice rather than predefined blueprints.

KOOZ The setting for this third workshop is quite unique in how soft and inviting it feels. How did you approach the design of the space for gathering? In what ways do you think spaces shape the kinds of exchanges that take place within them?

GA At the beginning, we didn’t really know what we wanted with this idea of a flexible or fluid space. But what’s fascinating is how, through the process of designing a space where we can all spend time together, certain ideas begin to emerge — ideas about world-making, about the structures from which we think and share. These start to take shape almost naturally.

It’s also interesting to see how these processes materialise in very subtle ways — in small design decisions, in cultural gestures, or even in the way the space is organised. This makes us reflect on the responsibility of architecture today: to imagine and propose new ways of operating, of creating spaces that allow for new kinds of encounters and thought.

Of course, this is always a collaborative endeavour — one that brings together many people with very different backgrounds and knowledge. And that, I believe, is the beauty of it: reconnecting and rethinking from these diverse perspectives, from the technical to the administrative, and everything in between.

And this is how the Institute began — rooted in the desires of people eager to understand how contemporary pedagogical spaces might challenge and question the deeply hierarchical relations that still persist within education. We often say that today we are not necessarily facing a crisis of ideas or of thought, but rather a crisis of methodologies — of systems, of the ways we do things and imagine alternatives. This is precisely what we try to explore with everyone who passes through the platform.

So it remains a constant question: how do we operate within these models, these tools, these platforms? We felt that the invitation to participate in the Um Slaim School resonated deeply with our ongoing inquiries, our challenges, and our frictions, as well as with our desire to think and act collectively alongside other practitioners.

BUILT / UNBUILT: Pedagogies of Proximity and Relation session with Institute for Postnatural Studies. Courtesy of the Architecture and Design Commission, the Commissioner for the National Pavilion of Saudi Arabia.

About

The Um Slaim School grew from the research-driven work of Syn Architects and the Um Slaim Collective — originally focused on vernacular Najdi architecture — into an alternative pedagogical prototype to be established in Riyadh after the Biennale. Aiming to redefine architecture education in Saudi Arabia, it fostered transnational dialogue on practice-led and research-centered methodologies, exploring how architecture can recalibrate relationships among natural, social, and technological systems through regenerative and participatory approaches. Guided by terms such as Matrilineals, Situated Practice, DIY Archiving, Ritual Matter, Adaptive Reuse, and Sprawling Grids, the program developed a situated spatial vocabulary while pursuing actionable outcomes for the School’s future. The Public Programme Biennale sessions — titled BUILT /UNBUILT — were built around core thematic investigations which included: Archiving Otherwise; Material Ecologies; Pedagogies of Proximity and Relation and Building Participatory Infrastructures. The programme was curated by Beatrice Leanza and co-led by Maryam AlNoaimi.

This conversation is excerpted from one of four readers documenting the laboratory activities, conversations, and key participants of the public program organized in Venice from June to November, as part of the Pavilion of Saudi Arabia—The Um Slaim School: An Architecture of Connection. These readers serve as companion pieces to the two publications produced as part of the Pavilion project, both co-published by Mousse Publishing and Kaph Books.

The Um Slaim School: An Architecture of Connection – 19th International Architecture Exhibition. La Biennale di Venezia (Mousse Publishing & Kaph Books, 2025)

Connections as Method: Relational Pedagogies and Participatory Spatial Practice (Mousse Publishing/Kaph Books, 2025)

Bio

The Institute for Postnatural Studies is a centre for artistic experimentation from which to explore and problematise postnature as a framework for contemporary creation. It is conceived as a platform for critical thinking that brings together artists and researchers concerned about the issues of the global ecological crisis through experimental formats of exchange and the production of open knowledge. From a multidisciplinary approach, the Institute develops long-term research focused on issues such as ecology, coexistence, and territories.

Gabriel Alonso is a visual artist and researcher whose practice lies at the intersection of ecology, science, and critical theory. His work investigates the contemporary shifting relationships towards nature, exploring new relations between matter and narrative, proposing new ways of bonding beings, technologies, and their environments.

Daniel H. Rey is an independent curator working on contemporary art and design storytelling, curation and programming in Madrid and its regions of influence.

Yuri Tuma is a multidisciplinary Brazilian artist living in Madrid, where he co-founded the Institute for Postnatural Studies and practices as its Academic and Artistic Co-Director. Yuri’s practice focuses on the investigation of contemporary narratives related to sonic and queer ecologies through collective healing practices, active listening, sound art, installation, and performance.

Federica Zambeletti is the founder and managing director of KoozArch. She is an architect, researcher and digital curator whose interests lie at the intersection between art, architecture and regenerative practices. In 2015 Federica founded KoozArch with the ambition of creating a space where to research, explore and discuss architecture beyond the limits of its built form. Parallel to her work at KoozArch, Federica is Architect at the architecture studio UNA and researcher at the non-profit agency for change UNLESS where she is project manager of the research "Antarctic Resolution". Federica is an Architectural Association School of Architecture in London alumni.