I originally started this column by recounting heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, floods, food shortage, energy crisis, soaring living costs, crumbling global supply chains, escalated geopolitical tensions, pandemics that perpetuate, moods of exhaustion that sweep across societies and so on and so forth. Then the list got too long, and it sounded like a broken record of daily news’ headlines.

Yes, the circumstances are pretty precarious. Established points of reference stopped making sense. Take the simplest - that the UK saw unprecedented 40°C in the summer of 2022 is less of an issue than that this may well be the coolest summer from now on. The traumatic loss of coordinates in time, in space and in sense-making is indeed unsettling.

Film still from Taming the Garden, 2021, dir. Salomé Jashi © Mira Film / Corso Film / Sakdoc Film

We are confronted by a historical opening. Our lived experiences can and should be taken as a point of departure towards reckoning our relationships with others, humans and more-than-humans.

Yet, precisely because of this, it cuts wide open the status quo. What is far more difficult than learning new things is unlearning established habits, especially when it comes to frames of mind. We are now in a time in which norms and consensuses are shattered by reality itself on a daily basis. This is significant. No need for any grand moments of revelation; just look around and breathe it in. We are confronted by a historical opening. Our lived experiences can and should be taken as a point of departure towards reckoning our relationships with others, humans and more-than-humans, and towards melting down established perspectives and mindsets for new ones to emerge.

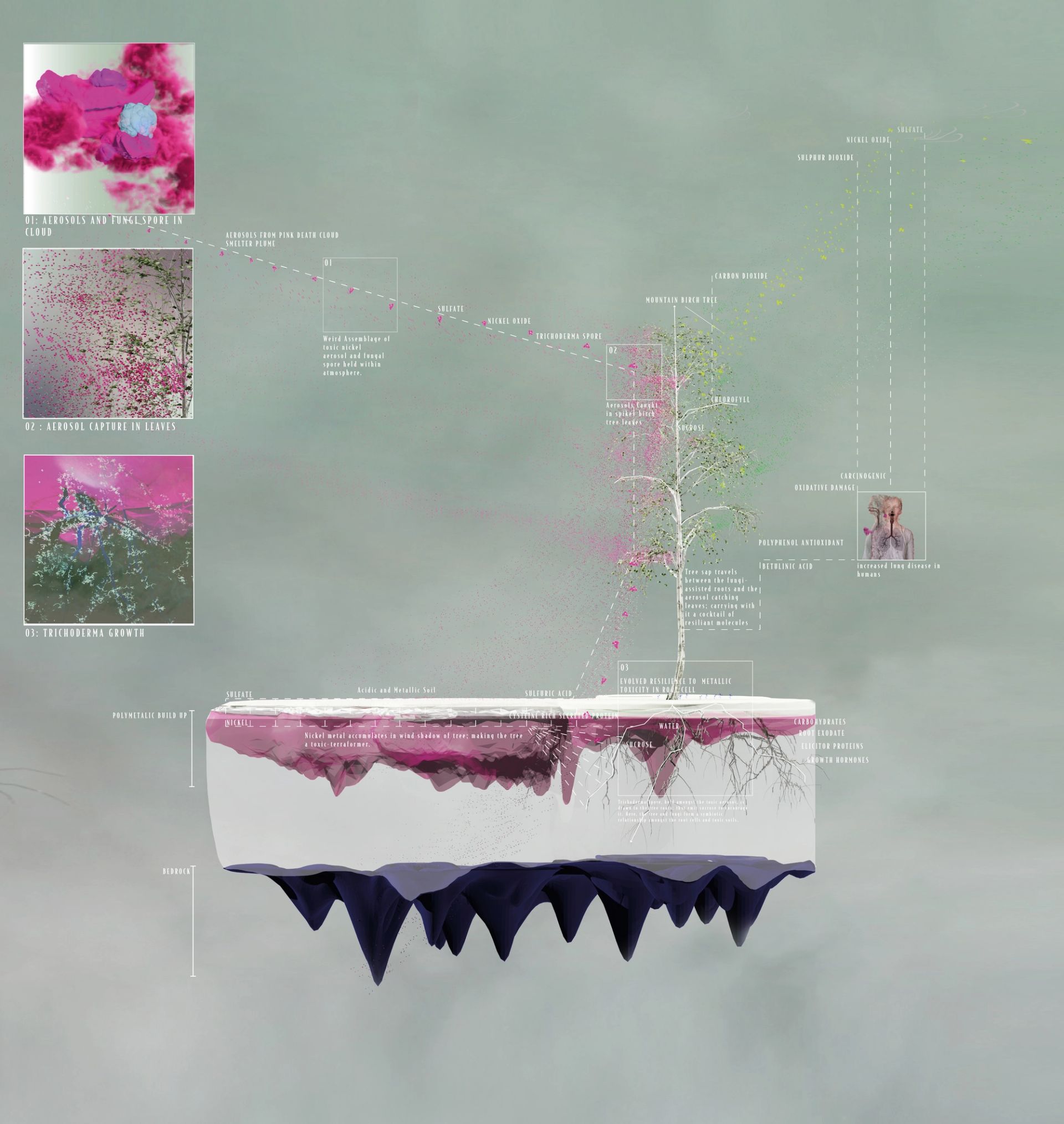

In the Pink, 2020, graduation project by Rosa Whiteley, ADS7 2019-20, Royal College of Art School of Architecture

Precarity as a condition is as epistemological as it is material. When we talk about modes of thinking or frames of mind, we are talking about it mostly as a character of an individual or entity. But, very crucially, it is also a character of the context. Without going into the Foucauldian notion of the episteme (i.e. conditions of possibility of knowledge),1 let’s take something seemingly scientific and common sense: the water cycle diagram. Upheld as a paradigm of modern hydrology, it was in fact modelled based on the temperate hydrological conditions of Northwestern Europe and Northeastern America at the time of its conception - which does not represent vastly different water conditions and how people live by them in other parts of the world. So, more precisely, it is a diagram of the historical and geographical circumstances of its making.2

Precarity as a condition is as epistemological as it is material

At large, modernity, or the modern paradigm of progress, is rooted in conditions of predictability and control that operate on a universal, linear timescale (ever-growing economy, higher productivity, more advanced technologies, just to name a few). This also moulds the modern mind. Yet, what we are living through now - from everyday life to the outlook of the geological epoch, from one’s living room to the planet - is shaking this very context to its core.

However, the thinking habit formed by certainty conforms to a default desire for certainty, still looking for radical, revolutionary solutions or universal, elementary models, ones that just might be trapped and paralysed by their own purity.3 “This kind of bleak certainty misses how things are.”4 The ground is melting, literally. The melting down of established mindsets, thinking and knowledge needs to catch up.

Film still from Asia One, 2018, dir. Cao Fei. Courtesy of the artist, Vitamin Creative Space and Sprüth Magers.

To think with precarity is challenging, in that it entails acknowledging our vulnerability, enacting interdependency with others and other lifeforms,5 and embracing indeterminacy when it comes to the future. Or simply, it subverts narcissism. Then the question is: how to take a nexus of indeterminate, ambiguous relations as the basis of being, knowing and practising?

To think with precarity is challenging, in that it entails acknowledging our vulnerability, enacting interdependency with others and other lifeforms, and embracing indeterminacy when it comes to the future.

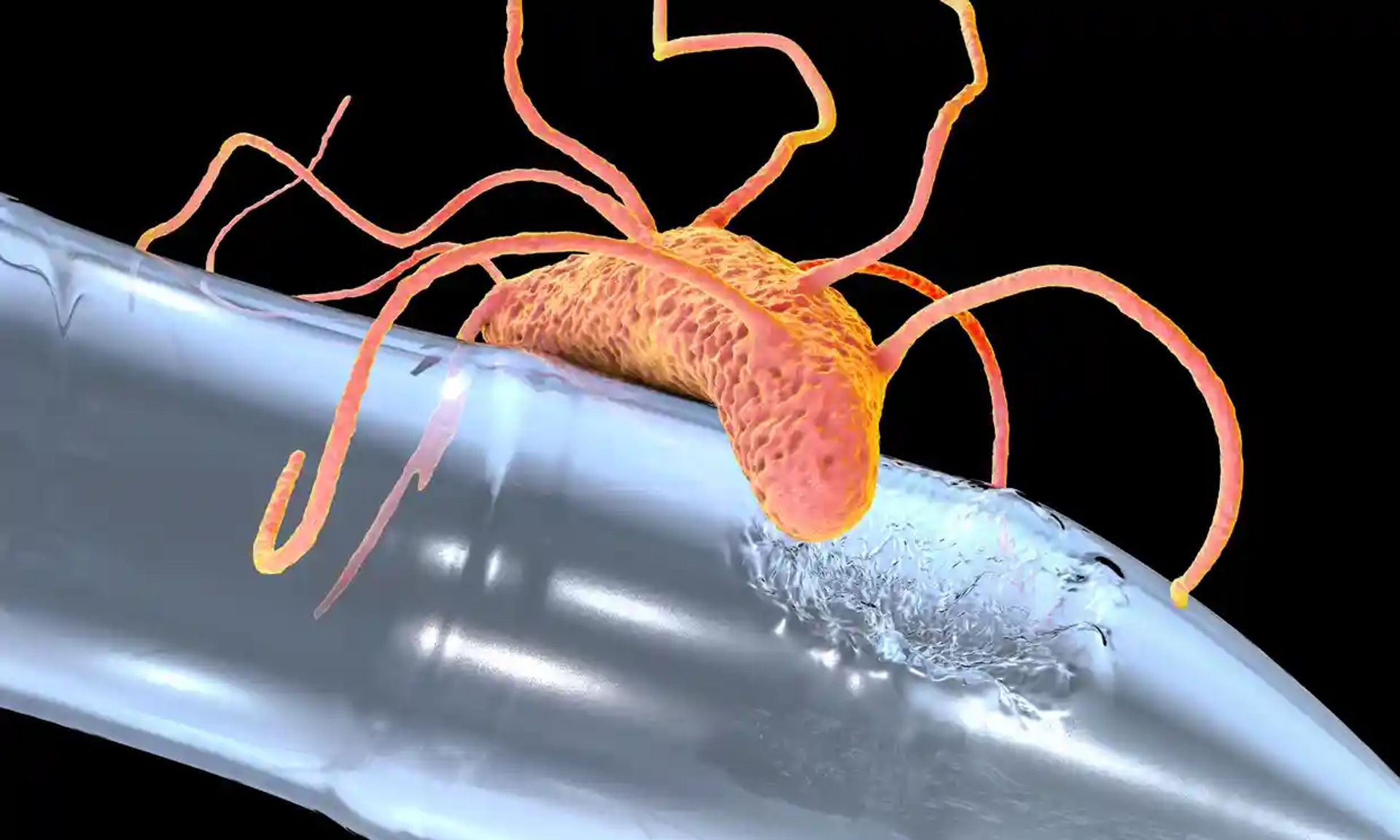

If the planetary feedback loop that connects herds of Yakutian horses, yaks, reindeers and others in the Siberian Arctic, the grassland ecosystem, the permafrost as carbon reservoir and greenhouse gases warming up the Earth’s surface feels a bit too distanced, even though it is certainly not,6 then think of the last time a single-use plastic container passed through your hands. It might even be too fleeting to be remembered. Yet, this moment of instant convenience cracks open the abyss of deep time: On the one hand, the hundreds of thousands of years of fossil fuel production that takes form in our daily life as single-use plastics,7 and on the other, the centuries in the future of plastic nanoparticles circulating through soil, water and air, getting registered in the lungs and bloodstreams of future generations. Somewhere in-between other lifeforms and their life cycles get caught. Sea turtles choke (mistaking plastic bags for jellyfish), dolphins drown (tangled up in packaging), and albatross chicks die of starvation (with a stomach full of plastic resin pellets),8 while plastic-eating bacteria are recently found growing in a plasticised marine environment or the plastisphere, a synthetic ecosystem at sea.9

Ideonella sakaiensis is a recently discovered bacterium that has the potential to ‘eat’ plastic waste. Source: Dr_Microbe/Getty/iStockphoto

Be relational. Individuality is overrated.

The above is to say: be relational. Individuality is overrated. The feeling of insecurity when one’s individual sphere is seemingly being transgressed is a first step towards attuning to relationality. What is being secured after all and at the expense of what? To know one’s position in the world (instead of “we are the world”) and in relation to others - humans and more-than-humans - is first of all ethically and politically important. It is also a transversal mode of sensing and sense-making: see connections between dots that seem completely unrelated, out of sync or at odds with causality, feel them, and let them have an impact on you. It smashes anything taken for granted. It unleashes imagination.

Read the entire "Living with Precarity" column by Jingru (Cyan) Cheng.

Bio

Jingru (Cyan) Cheng is a transdisciplinary design researcher. At the intersection of architecture, anthropology, performance and filmmaking, Cyan’s collaborative work is committed to generating new sensibilities and imaginaries. The wide-ranging themes include non-canonical frameworks of being, knowing and practising, aesthetic agency, and modes of co-existence between human and more-than-human. Cyan received commendations by the RIBA President’s Awards for Research in 2018 and 2020 from the Royal Institute of British Architects. Her work has been exhibited at Critical Zones: Observatories for Earthly Politics (2020-22), Driving the Human: 21 Visions for Eco-social Renewal (2021), Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism (2019), Venice Architecture Biennale (2018), among others, and included in the Architectural Association’s permanent collection. Cyan holds a PhD by Design from the Architectural Association (AA), and was the co-director of AA Wuhan Visiting School (2015-17). She currently teaches at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London.

Notes

1Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London : Routledge, 1966/2018).

2 Jamie Linton, “Is the Hydrologic Cycle Sustainable? A Historical-Geographical Critique of a Modern Concept,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98, no. 3 (2008): 630–49.

3 Keller Easterling, Medium Design: Knowing How to Work on the World (London: Verso, 2021).

4 Timothy Morton, All Art is Ecological (London: Penguin Books, 2021), 21.

5 Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2021).

6 This planetary feedback loop mainly refers to the long-term geoengineering project known as Pleistocene Park. More on this, see Ross Andersen, “Welcome to Pleistocene Park,” The Atlantic, April 2017.

7 Heather M. Davis, Plastic Matter (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022).

8 Chris Jordan, “The Pacific's plastic shame,” The Guardian, 4 November, 2009.

9 Russell Thomas, “Welcome to the ‘plastisphere’: the synthetic ecosystem evolving at sea,” The Guardian, 11 August 2021.

Bibliography

Davis, Heather M.. Plastic Matter. Durham: Duke University Press, 2022.

Easterling, Keller. Medium Design: Knowing How to Work on the World. London: Verso, 2021.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. London : Routledge, 2018.

Linton, Jamie. “Is the Hydrologic Cycle Sustainable? A Historical-Geographical Critique of a Modern Concept.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98, no. 3 (2008): 630–49.

Morton, Timothy. All Art is Ecological. London: Penguin Books, 2021.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2021.