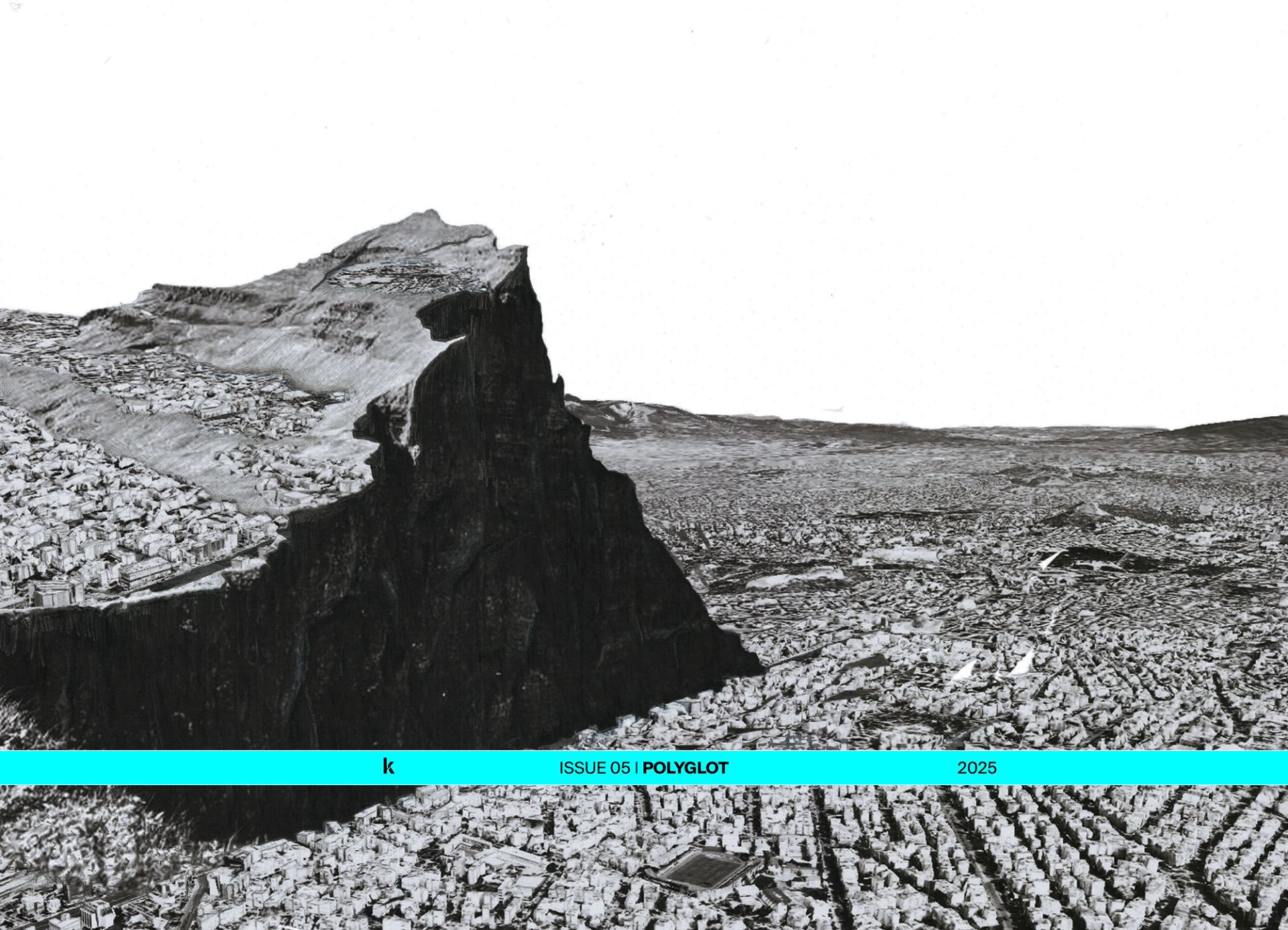

Part of the "De-Activated City" series.

Mere digitisation cannot compare with the engagement of real-world experience. In fact, storytelling and an enabling environment are essential elements for offering users an active role when interacting with cultural heritage. Initially considered a world existing in parallel to the “real” one, today digital information is increasingly becoming embedded in the physical world – effectively becoming a unified, hybrid version. Methods for the digitisation of museum collections and virtual exhibitions, although not entirely new, are becoming more and more widespread due to the physical limitations to prevent Covid-19. Communication methods used by the cultural sector were particularly affected by the pandemic. Challenges arise especially due to faulty user experience and to the digital divide. The empathic and social experience of cultural heritage is a critical but substantial gap that is often missing from the promotion of culture and arts through online media.

We explore seven successful hybrid experiments that took place in Rome during the pandemic era. These three different methods for promoting and allowing access to cultural heritage integrate digital and physical elements. The main difference among them lies in the adoption of precise storytelling and in the creation of an enabling environment.

The first type of experiments is entirely focused on digital contents, such as “A Short Video History of (Almost) Everything” and the New Year’s Eve event of the Municipality of Rome “Oltre Tutto”. Their storytelling promoted digital access to cultural functions, such as museums and archaeological sites closed during lockdowns. The enabling environment of these initiatives is still limited to the digital medium.

Secondly, physical events with additional online contents, such as “Back to Nature”, “Art Stop Monti” and “Life in the times of Coronavirus”. Here, art pieces are integrated in public spaces —parks, metro stations and city walls— and the public is invited to further explore digital contents. Such storytelling builds upon the practice of “diffuse museums”, leaving to any passer-by the freedom to learn more about the initiative and the artists involved — and share these contents on social media.

Third, experiments structured around a harmonic integration of physical and digital media. The projects “Change Architecture Cities Life” and “Viaggi nei paraggi” dwelled on how the abrupt changes of Covid-19 affected our cities and surrounding environment. The public could therefore attend events in their own neighbourhood and throughout the city, while some of these events were entirely digital — roundtables, workshops, tours and mapping.

Besides creating and communicating culture, the synthesis of these different methods is also an attempt of returning to business-as-usual. These projects are experiments narrating how Covid-19 changed our interaction with and enjoyment of cultural heritage. Technology, in this sense, can help overcoming limitations to physical interaction, and maintain (and enhance) human and social aspects of cultural heritage in the post-pandemic context. These experiments show that Rome is experiencing a cultural stir thanks to both institutionalised and independent initiatives. The cultural sector of the city is entering a more mature stage, defining new possibilities of innovation and resilience in the diffusion of cultural contents through online media. These new cultural practices could effectively answer the urgent need for transforming the relationship between cultural heritage and digital technologies.