Abstract

The matter of architectural representation as a translation of the internal space of a building is a territory with many well-trodden paths. But in this vast field, the radical acts, old and new, stand out to prove the ever-expanding possibilities of representing the multiple dimensions and meanings of space. This paper intends to bring into discussion two forceful gestures. The first one belongs to Luigi Moretti, who during the 1950s, built an unorthodox method of representing the internal space of churches and other important buildings in the history of Italian architecture, by stripping the edifices of their external meshes and turning the void into matter through plaster-cast models, showing the true shapes of the architectural body in his magazine called Spazio. The other one is the spatial survey Baroque Topologies by Andrew Saunders, who 60 years later, turns to the latest technology, using laser scanning, photogrammetry and digital imaging to translate the space into big data, using Luigi Moretti's study as reference. From one solid to million point cloud, the poiesis (coming into being/emergence) of space becomes a represented reality and a mental entity, being built, unbuilt, rebuilt, manipulated according to the author's will and vision.

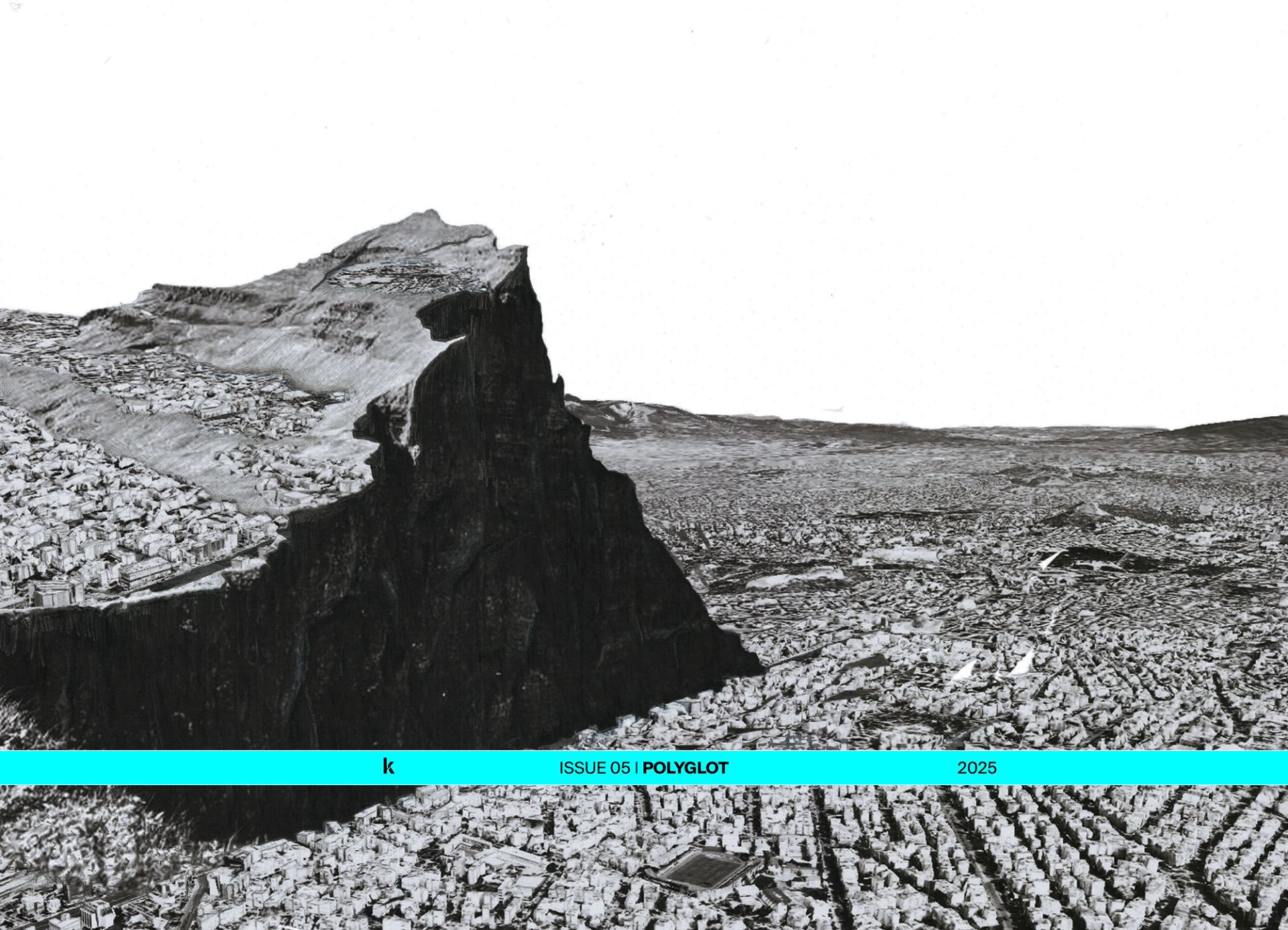

Taxonomy. Baroque Topologies by Andrew Saunders

The Body of the Unbuilt

“There is, however, an expressive aspect that summarises with such a remarkable freedom architecture […]: I refer to the internal space and the void in architecture. […] The internal space is the main reason, or even the reason from which the building arises, it is revealed as the seed, the mirror, the richest symbol of all architectural reality. […] The internal volumes have their own concrete presence, regardless of the figure and the material that encloses them, as if they are formed of a rarefied substance devoid of energy but very sensitive at receiving it.”¹

The graphic metalanguage of the plaster models depicting canonical Italian buildings became for Moretti the perfect instrument to conceptualise the idea of architecture as cast.

These selected passages from the seminal essay Strutture e sequenze di spazi comprise, in a few phrases, Luigi Moretti's bold vision of architectural space, developed and published in his eloquently entitled Spazio magazine. The seven issues of Spazio, built from 1950 to 1953 like a series of seven rooms of thought, conclude with the aforementioned study to ideally materialise Moretti's inquiries, both through text and visuals. The architect's choice to assign a physical and material consistency to the void, transforming it into a corporeal solid with its own determined parameters and qualities, constituted a radical act at its time, especially in terms of visual representation. The graphic metalanguage of the plaster models depicting canonical Italian buildings became for Moretti the perfect instrument to conceptualise the idea of architecture as cast, of space as a negative turned into positive, passive in form but active through cognitive mechanisms. The abstract representation implying the reduction of the interior space to its static essence was applied to very diverse architectural objects, carefully picked from different periods of history in order to create an operative taxonomy. The scope of this taxonomy was, among other purposes, to declare that the history of architecture coincides with the conquest, control and evolution of internal space and the role of architecture is that of Raumgestalterin (“creatress of space”).²

In Moretti's scientific-artistic laboratory, the unbuilt, generally seen as a vacuum shaped by the built, accumulated matter and turned itself into a mental and corporeal construct.

In Moretti's scientific-artistic laboratory, the unbuilt, generally seen as a vacuum shaped by the built, accumulated matter and turned itself into a mental and corporeal construct. The internal space of the edifice thus came into presence, showing its own body and physiognomy, stripped off its clothes and masks—the abstract expression of a pure void devoid of any formal accents. The concretised presence of space inextricably bore the imprint of its mould, a non-presence still possible to rebuild in the mind due to the marks left, visible through the dilatations and pressures it forced on the internal composition poured inside of it. Extrapolating the idea that the plaster is a material which holds the memory of the manual exercise and of its outer shell, one may say that the model of the internal space was not a precisely presented reality but a represented memory of space as a result of intense observation, contemplation and successive vision.

Since the void-turned-into-solid assumed the strong value of a sign, its meanings are numerous and subject to interpretations. But these parlante objectsthat Luigi Moretti modelled, though abstract and metaphorical in some senses, rigorously held a mathematical logic in their structure, as they were meant to express the constructive feeling of a building and the complex “algorithmic and enclosed nature” of architecture. With the term “algorithm” Moretti described the existence and evolution of different (systems of) structures of values which, through their relationship, form the general structure—the form of a building—seen as a “reality of pure interrelationships”. These systems of values are comprised of “the geometric form, simple or complex as it may be, dimension, intended as the quantity of volume, density, which depends on light, and, finally, the energetic pressure or charge exercised by masses at each point in space”, with each of these parameters constantly and dynamically influencing one another. The spatial qualities mentioned by Moretti, such as pressure and the energetic charge of a space, show an operative way of understanding history by implying scientific notions put at the service of architectural poetic.3

One of the many purposes of his endeavour was to reformulate the relationship between structure and form, between structure and structure, between form and form.

He critically and constantly returned to the grand masters for the “precise intuition of structure, for the mathematical fantasy of spaces.”4 One of the many purposes of his endeavour was to reformulate, in a logical-mathematical key, the relationship between structure and form, between structure and structure, between form and form (all of these having their own different system of values, all interrelated, readable in the spatial units of sequences). The spatial algorithm was translated by Moretti as a spatial concatenation between the internal volumes, with a complex composition in which the elements reveal themselves through the differences between one another.The conjunctions were to be understood on all the possible levels, transmitting the idea that everything is related in an accumulation of systems of parameters inextricably linked to one another. Moretti's image of space was thus constructed through an evolutionary, perceptive and mnemonic chain5 according to a clearly defined logic. His algorithmic thinking, which was developed along with his operative research, allowed him to introduce, in his architectural studies, embryonic notions of parametricism, mechanical physiology, computational design and cybernetics,6 which remained just at the state of seeds due to the available technology at the moment (one may only wonder how far his studies would have gone if the current tech instruments were at his disposal).

Luigi Moretti's vision of space, the double nature of his Janus-like figure, is simultaneously looking at the past and at the future.

Drawing a line after this very comprised analysis of Luigi Moretti's vision of space, it is worth highlighting the constant duality of his endeavours, the double nature of his Janus-like figure (which is readable on many levels) simultaneously looking at the past and at the future. The strong logical side, the perfectly objective investigation of space opposed (or completed) the subjective one, in which architectural space was for him a generator of passions, emotions and affections. His representation of space might be considered a sort of rational poetry full of metaphors, with abstract and concrete sequences in which imagination could freely conjunct the lines.

Spheroidal Cosmologies. The cupolas of the San Silvestro designed by Francesco Da Volterra, Rome, Italy. © Andrew Saunders, Baroque Topologies

The Solid (thinking) is Granular

“The geometric world is quantitative: granular space (Greek atomists) (granular thinking: as much as logical thinking) – The quantitative progress of knowledge. We perceive the class, not the particular element. ”These notes taken from Moretti's Taccuino are yet another way of consolidating his theory—space is not a void, but a dense substance, a continuum made of concatenated elements differentiated through their qualities. The granular space is “comprised of the same granulose substance as the intellectual structure of man, which determines a type of knowledge by granules.”7 (What better way to express this idea than choosing to represent the internal space of a building by using plaster as a material to build one solid, with its conglomeration of calcium sulphate granules and water?)

Space is not a void, but a dense substance, a continuum made of concatenated elements differentiated through their qualities.

Extending and converging all these lines of thinking and points of views, we reach the present day to find contemporary hypostases of Moretti’s views from the 1950s, revealing new surprising instances of granular thinking through what we may call big data pointillism. For this, Andrew Saunders’s study entitled Baroque Topologies comes to offer relevant answers on multiple matters: how to manipulate the spatial conception of the original Moretti analysis, how to plug it in and adapt it to the latest technologies (that Moretti partly anticipated and dreamt of), how to understand and represent the complex reality of architectural space in the context of big data. This novel research, while operating with and updating the aforementioned notions that Moretti forecasted (from algorithmic thinking, computational instruments, granular cumulation of information, space as void etc.), shows new points of unexpected views, connecting and distancing itself from the reference, while focusing on one specific type of space—Baroque.

From One Solid to Million Point Cloud

In Baroque Topologies, granules of information find concretisation in different hypercomplex computer-generated forms, with scanned measurements distributed in a precise matrix of millions points tracing the exact three-dimensional figure8 of the internal space of Baroque churches. LiDar (Light Detection and Ranging) laser scanning, along with photogrammetry, capturing three-dimensional coordinates and colour-data, allow a direct 3D transposition of the actual geometry of the unbuilt—rebuilt virtually in one precise digital model equivalent to the real form. The conglomerate of scanned points are matched together through an algorithmic registration process that identifies similar patterns in separate scans to align them correctly, creating a mesh. This thin membrane made of million granules is the virtual millimetric layer between the interior space and its container, the skin slightly touching the heavy poché of the church walls.

The Diaphanous Body is unfiltered and completely open due to its transparency obtained by the spacing of points, allowing the look to penetrate the space, both from the outside and inside.

The first hypostasis in which Andrew Saunders shows us the Baroque space is through the Diaphanous Body and its translucent physicality (corresponding to the idea of space as an “incorporeal body”—corpo incorporeo—used also by Moretti). The Diaphanous Body is the pure information of the survey, unfiltered and completely open due to its transparency obtained by the spacing of points, allowing the look to penetrate the space, both from the outside and inside. In this case, the representation is no longer a translation (which implies interpretation and subjectivity), but an objective transfer of information from reality to virtuality—thus, surveying becomes the new critical-radical act of total spatial representation, not a just a presentation of the measure of space, not an idealisation of forms, not abstract speculation. “We now have an analytical method of representation where nothing is idealised and everything exists in equally high resolution and precise reconstruction (accurate up to 0.2mm).”9 This first stage of direct representation (which is more about capturing, recording, documenting) allows the Diaphanous Body of space to be further manipulated, to gain consistency and be materialised in another phase of Andrew Saunders’s research—the Figured Void.

The Figured Void series solidifies the unbuilt in an non-reductive, definite and figural way, making explicit all the details essential for the total comprehension of Baroque space.

Clearly building itself on Luigi Moretti’s body of study but detaching from the process of modern abstraction, the Figured Void series solidifies the unbuilt in an non-reductive, definite and figural way, making explicit all the details essential for the total comprehension of Baroque space. Contrary to Moretti’s notion of space as a sequential composition of volumes, Andrew Saunders focuses on the autonomy and the objectness of the manifold body, figuring his Baroque void as one articulated form — “a precisely calibrated entity, capable of being comprehended as an autonomous spatial capsule, an effect driven machine”.10 To evoke the seemingly continuous movement of the Baroque apparatus, activated by ornament, colour, light, painterly effects, the Figured Voids exceed the field of digital imagery and immersive virtual simulation to find concretisation in 3D printed models made of photopolymer resin. Retaining the qualities of the first stage of Diaphanous Bodies, the physical models are the negative translucent casts of the interior spaces. The material triggers visual and tangible sensations, dynamizing the perception by allowing the eyes to pierce in depth until reaching the nucleus of space and the light to enter the model until activating different colour hues.

Looking at the overall images on both sides, the representation of space in Baroque Topologies might be considered, in comparison to Moretti's metaphors, a complex and precise narration rich in itself, denying the necessities of embellishing the story line and finding value in the pure state of accurate information.

In terms of conception and architectural representation of space, big data and new technologies have completely changed the game.

Versus

“One should always bear in mind that new plastic creation without a change in spatial concept, cannot be considered as an architectural renewal, since the highest aim of architecture is the creation of space.” (Albert Erich Brinckmann)

It is obvious that in terms of conception and architectural representation of space, big data and new technologies have completely changed the game. This was clear from the time when Luigi Moretti was pouring his plaster models and anticipating the future massive intervention of computational tools. Although the paradigm has transfigured, the spatial studies of the 1950s offer (still) strong foundations to built upon, with new constructs following or partially denying the old structure, like the case of Andrew Saunders. The way of looking at space is different depending on the lens and the way of representing space is different depending on the available technology, but instruments are, after all, mediators and enablers, affecting the process of gaining knowledge.

The plaster model is a distorted mirror with multiple sides, showing real and conceived hypostases through the process of abstraction.

Comparing the studies of Luigi Moretti and Andrew Saunders, it is clear that there is an inversion in the process of analysis and representation of canonical buildings, the order of the phases is switched (also due to the available technology). For Luigi Moretti, the analysis and the cognitive process is prior to representation which is both the means and the result. The plaster model is a destructured reality of space recomposed as a sequence according to objective scientific parameters, but at the same time it is inherently linked to the personal algorithm of the author (with the interference of memory, imagination and emotion). It is a distorted mirror with multiple sides, showing real and conceived hypostases through the process of abstraction, which for Moretti is the way to express his idea of architecture as “reality and representation”. In the case of Andrew Saunders’s research, the representation (the survey) comes first, then the analysis and then the re-representation (critical manipulation and interpretation of precise data). The digital and printed models are mirrors with novel vantage points showing realities that exist without being normally visible to the human eye through direct observation. This digital mirror, which overexposes the naked body of space, does not leave much room for idealisation and imagination (but plenty for interpretation) since everything, everywhere is visible all at once, for the purpose of a ‘total’ non-reductive knowledge. In the end, this type of representation assumes the radical role of an accurate machine and remains true to itself by expressing the current zeitgeist, just like Luigi Moretti's abstract solids were reflections of his time.

The digital and printed models are mirrors with novel vantage points showing realities that exist without being normally visible to the human eye.

In any of those cases, the authors put at the disposal of the viewers extraordinary lenses to look at the architectural space. The diachronic connections that can be made between the voids of Luigi Moretti and Andrew Saunders can be considered another type of fruitful concatenations built in time and space, a chain that can be further continued with further interpretations, which proves the relevancy and value of their inquiries.

Bio

Andreea Mihaela Chircă is a PhD student at “Ion Mincu” University of Architecture and Urban Planning Bucharest, currently developing a research project in co-tutorship with Sapienza University of Rome. Her thesis investigates experimental methods of representing space in the Italian architectural practices and pedagogies from 1950s-60s. The matter of representation is also exploredon a virtual non-linear journey through visual references, at the intersection of art and architecture, shared on a small platform @poiesisofspace.

Notes

1 Luigi Moretti, “Strutture e Sequenze di Spazi”, Spazio, n.7, December 1952 - January 1953, p. 10.

2 August Schmarsow, “The Essence of Architectural Creation” in Mallgrave and Ikonomou, Empathy, Form, and Space,a translation of the lecture “Das Wesen der architektonischen Schöpfung” given in Leipzig, 8 November 1893), 287.

3 Marco Maria Sambo, “Estetica del '900. Poetica del Contemporaneo. Linguaggio eclettico e parametrico”, AR Magazine, n. 125/126, July-August 2021, p.28.

4 Agnoldomenico Pica: “Luigi Moretti architetto”, written in occasion of the awarding of the Premio Nazionale di Architettura by the President of the Italian Republic Giovanni Gronchi, 1957.

5 Annalisa Viati Navone, “Il Barocco alla luce del Taccuino. Una traiettoria intellettuale costruita a posteriori”, AR Magazine, n. 125/126, July-August 2021, p. 233.

6 Navone, p. 223.

7 Navone, p. 233.

8 Andrew Saunders, Baroque Topologies (Modena: Palombi editori, 2018),p. 61.

9 Saunders, p. 117.

10 Saunders, p. 65.