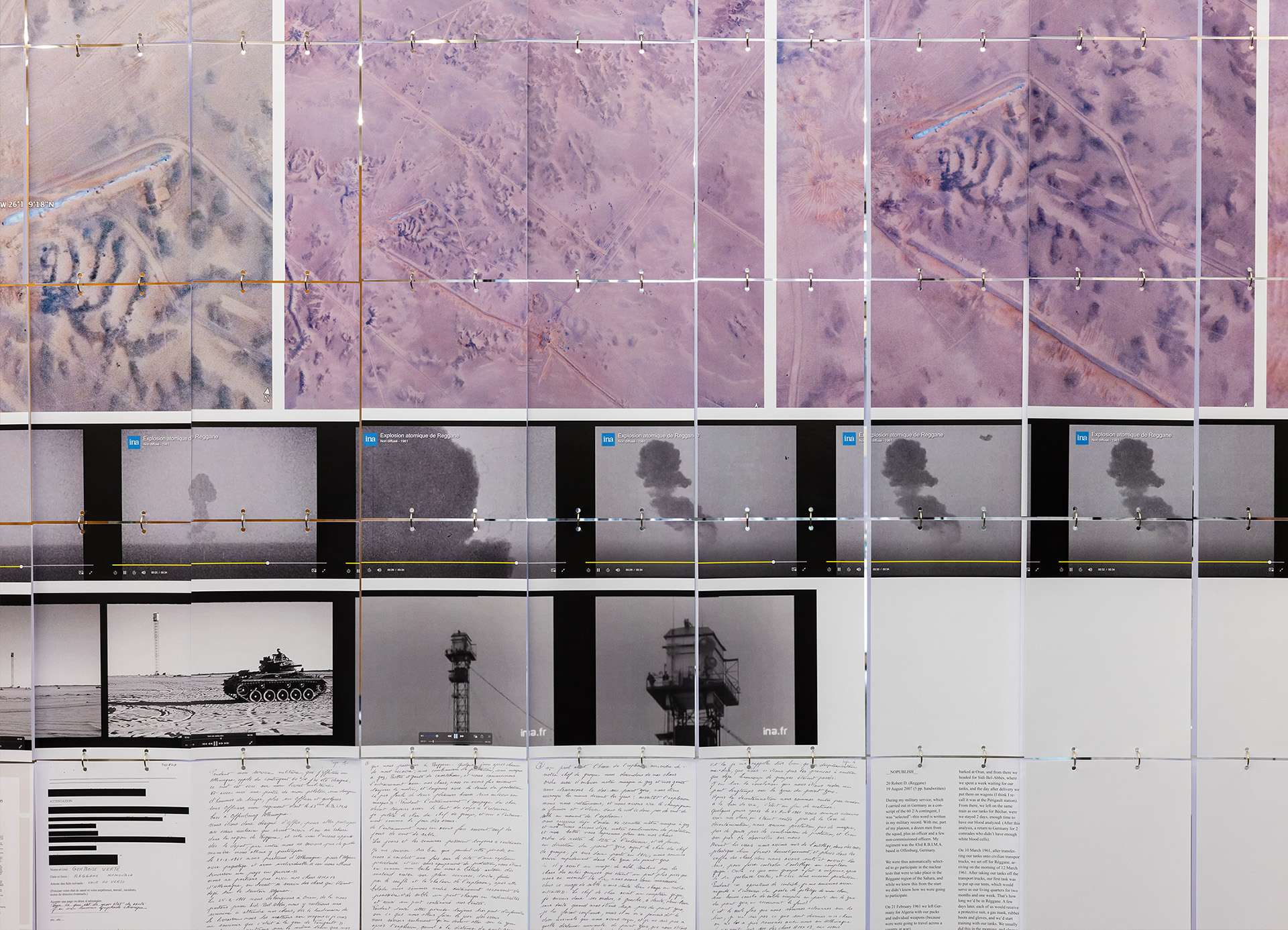

Oases are commonly associated with the idea of refuge and the prospect of escaping necessity. The vulnerability of this microcosm becomes a potent symbol of protection where the idea of irrigation takes a central role, suggesting that the oasian space necessarily results from an anthropic architectural action and relies on continual maintenance. Ines Tazi’s project "An oasis of our own"—developed at the Architectural Association in the diploma unit of Maria Shéhérazade Giudici and Pier Vittorio Aureli—posits that, as an ambivalent paradigm of appropriation, the oasis often becomes a contested place when necessity becomes instrumental to centralised forms of government and to the creation of allegiance the spatial archetypes that have derived from it.

In this conversation, we talk about the politics of space in Casablanca, what resistance and autonomy in the traditional garden look like and the agency of observation in contemporary architectural practice.

KOOZ What prompted the project? What questions does the project raise and which does it address?

INES TAZI One of the initial motivations of this project was to rearticulate the central idea of refuge in the oasis. It is a continuation of a paper which delineated a genealogy of oases by looking at the Persian chahār bāgh and monumental oasis gardens in southern Morocco. I considered their commonalities in terms of spatial layout and water management, and how they came to be formally understood as archetypes of an earthly paradise. An oasis gave the opportunity to leverage immense power, especially for centralised forms of government.

An oasis gave the opportunity to leverage immense power, especially for centralised forms of government.

I found that this particular appropriation of life sustenance—at least in the context of Moroccan politics—gave rise to a perpetual system of relationships driven by necessity, enabling the state and common institutions to intrude into the private sphere and progressively erode individual freedoms.

I imagined this project in my home city, Casablanca, because many of these socio-political legacies culminate and are quite perceptible here. It questions how to reclaim the initial idea of refuge in the oasis, and what a place which counters these ongoing conditions might perform and look like.

KOOZ The project, which unfolds as a proposition to create an archetype for places of resistance and autonomy in Casablanca, aims to counteract the control of subjectivities, stigmatisation and undermining of individual freedoms which are embedded in the only available spaces in the contemporary Moroccan city: the street and the family home. How does the project approach notions of resistance and autonomy?

IT With some exceptions, I would say this is the range of options for many people. In Casablanca, there are more alternatives, but most are burdened with unspoken rules which stem from normalised tough heteropatriarchy. Meanwhile, there is a substantial underground cultural scene in search of more physical spaces, where social interaction and circulation of emerging cultural initiatives—both individual or collective— can happen in a protected environment. With every protected microcosm there is a series of choices to be made beyond blind inclusivity and I think many different people could use an alternative space to cultivate meaningful connections beyond familial or institutional settings.

With every protected microcosm there is a series of choices to be made beyond blind inclusivity and I think many different people could use an alternative space to cultivate meaningful connections beyond familial or institutional settings.

The community gardens I propose in this project may be used to socialise, rehearse, organise, mobilise, or even simply to connect to the internet. They can be a place of opportunity for self-expression beyond the watch of classic institutions. I also wanted to draw a plan which could potentially accommodate overnight stays: there is a potential role of social refuge—especially but not exclusively for the queer community, young women, or anyone in need—to find a momentary escape from a deeply alienating situation. The project aims to reclaim forms of resistance, autonomy, and kinship through the activities and interactions it seeks to facilitate. This includes the gradual and collective establishment and maintenance of community gardens, which will serve as spaces for fostering these values.

KOOZ How do these definitions then spatially unfold through the archetype of the suffah garden as an alternative experience between regulated public and domestic space, to be a space of hospitality and creation where citizens can articulate their agencies?

IT Because of the possibility to regulate privacy, and because of the possibilities that another home to visit can offer, this project, with each garden and its access being handled by a collective, was thought around the idea of a semi-open house/dar. I also drew from the suffah, which refers to a raised platform for stigmatised or isolated individuals featured in the house of the prophet in Medina and other mosque typologies. The suffah was conceptually as well as spatially fitting, since it can grow along the edge of the wall enclosures.

With this suffah garden archetype, I wanted to imagine an accessible scheme which could unfold in many locations that share some qualities, such as enclosures and some existing greenery. They are initially included in relevant found sites and kept because they are essential to the design. The growth of existing trees and planting of new trees both anchor and project this place in a long-term scenario. Rooms and canopies along the edge allow for concealment and intimacy, while alterations of ground levels or textures in the void provide orientation or suggest areas of social gathering, performance, rehearsal, visiting, and so on.

I imagine that the growth of suffah gardens across a city enable the growth and sedimentation of networks of care.

KOOZ Beyond the single archetype, the project also speculates on the possibility of the suffah as a series of various enclosed sites forming a network of suffah gardens. What is the potential of this throughout a city of Casablanca but also as an urban system of cities?

IT This proposal became an opportunity to think of a space to be realised over a long time, in a sequence of stages, while also being operational from the very start. And, beyond the scale of a single garden, I also considered the timeline at the scale of the city (or beyond) with a network of suffah gardens. I imagine that the growth of suffah gardens across a city enables the growth and sedimentation of networks of care. And in that sense, this project takes into consideration the value of slow work within social organising, taking up physical space.

KOOZ As a project which has been developed through pen and paper, or better pixels and mouse, what is for you the power of the architectural imaginary to questions and propose diverse alternative to our status quo?

IT I think the power of the architectural imaginary, when developed through pixels and mouse, is to allow for political imagination. I would say that political imagination is mostly held up by political elites and ever-increasing economic pressures, rather than solely by the demands of built projects. Still, the architecture imaginary provides inspiration and continually engages us to be more daring and mindful in our propositions, and to design in service of these ideas.

The power of the architectural imaginary, when developed through pixels and mouse, is to allow for political imagination.

KOOZ Beyond the builder of buildings, where do you see your agency as an architect?

IT One aspect I particularly care about and see agency in is observation. It can be to be attentive to mundane patterns or, for instance, to locate social shifts in dwelling/migrating, and engage with their political stakes. Or it can be to contemplate how some people choose to articulate their desire or need for change. I see agency in developing sensible proposals —whether it is a building, a network, an object, a timeline— by questioning and communicating observations. Intervening in a context might also mean to intervene in a conversation, a policy or a mode of organising of resources. Though not at all limited to architecture, I also learnt more about being reflexive and accountable in architectural practice and learning.

Bio

Ines Tazi is an architect from Casablanca based in London. She graduated from the Architectural Association in 2019 and is currently practicing in an architectural studio in London, while finishing a masters in gender studies focused in the global south and courses on diasporas in the contemporary world as SOAS. Her personal projects explore the politics of space and migration in correlation with the body and cultural norms, combining research, writing, photography, and architectural design. Ines’ work was namely featured in the 2023 book Architecture of the Territory, and in the exhibition Omran 2019 curated and organised by Collective for Architecture Lebanon.