In this conversation, Mexican architect Tatiana Bilbao traces her longstanding commitment to notions of home and housing, and her undiminished belief in architecture as providing a primary form of care. This interview is published in collaboration with PIN UP magazine and features in the print edition of PIN–UP 39, guest-edited by Frida Escobedo.

Shumi Bose / KOOZ Tatiana, we’re going to talk about home and domesticity today, but I wanted to start at a zoomed-out scale. I enjoyed learning about your early career, advising the Ministry of Housing in Mexico. The domestic realm has been consigned to women for a long time, and not only in architecture.. Yet in your career, there’s a certain grounding in the civic and political scale of operations, which I think is a really interesting foundation.

Tatiana Bilbao Well, I was only 24, so I did not have much knowledge of domesticity. I did not have a family of my own; I had not lived by myself. But I always understood architecture as a primary form of care. I don’t think that I had defined it so clearly until about 10 or 15 years ago, but I definitely understood it the same way back then.

In Mexico, housing is not only a human right, it’s a constitutional right. So I always thought that this was my path, where I wanted to work. At first, I really liked the idea of the social production of space. I did my thesis on an urban plan for the historic center; my idea actually involved creating domestic realms in public space. We spoke about humanizing urban space, making it more pedestrian, more than a place to buy things. For me, it was definitely about the idea of domesticizing — I didn’t use that word at the time, but that was exactly what I was doing. While working at a really small firm, I was suddenly invited to work in the Department of Urban Planning and Housing — I couldn’t have been prouder. That’s really what I wanted; after that thesis, it seemed like my dream job. I just didn’t realize, until I was there, that it was not.

KOOZ That’s often the way, right?

TB The idea I had about working was really about being able to be the thinker, the designer of the future of social space, whether in public realm or private homes. When I was there, I understood that it was really much more about the administration of public space. I realized that I wanted to work in the private realm or in academia with the municipality, and that’s what I started to do.

KOOZ I can imagine the disillusionment — and the subsequent recalibration. But that led you to start your own practice, as Tatiana Bilbao Estudio in 2004.

TB Exactly. And as I said, I was definitely interested in housing already, as a constitutional right. That was a very big mandate for the Ministry of Urban Planning and Public Housing, where I worked.

KOOZ Do you think the appeal towards that mandate comes from that context where inequality is very visible? I mean to say, do you think this sense of clear civic responsibility towards housing a huge population comes from your context in Mexico?

TB Definitely. Understanding that architecture provides a basic form of care — serving a very basic human need — was very clear, because it’s so visible in Mexico City. It really is necessary and unfortunately, it’s something that has not yet been fulfilled for everybody. I studied at a very strange moment for architecture. It was the early 90s, and Mexico was going through a boom at the time. In architecture school, we were being taught that architecture was parametric, geometric forms produced by computers that we didn’t have and didn’t know how to use. But I had one professor who took us to build houses with our own hands in hill towns that were very poor — that was really where I learned. To me, that was architecture — not the parametric stuff we saw at school. With this professor, we built a house with the community. So when I graduated and went into the world, I saw architecture as providing this primary form of care. You don’t need expensive materials or geometric somersaults to provide basic needs. I began to realize that a house was not just a house. It’s not about designing a perfect plan to be reproduced on a massive scale. I started to think about the way we live. Domesticity is what we do every hour of every day, of our existence — in the hotel, the office, the beach, everywhere and anywhere. There’s not much of a divide between the domestic and the outside.

Designed in collaboration with Joselo Maderista, Tatiana Bilbao’s ¿Mesa para cuántos? envisions a table with an integrated set of chairs. Rejecting notions of standardized living, the furniture is designed to adapt to the needs and movements of the body within an ever-changing domestic choreography. Photography by Rafael Palacios Macías

KOOZ I guess we try to make the Earth inhabitable in various ways, sometimes against the will of nature, sometimes not. But I love the way you seamlessly put together the scale of the city, the country, and the house, flowing between them.

"I think that our condition is intrinsically linked to our human scale; we need our own individual bodies to exist on this planet but we also need each other. […] I understand domesticity as this extension from your inner body out to the social life that we live within."

TB I think that our condition is intrinsically linked to our human scale; we need our own individual bodies to exist on this planet but we also need each other. When I said a house is not just a house, it’s about creating this condition which is both intimate and social. There are spaces to be with your intimate being and spaces for your fulfillment and for interconnectedness I understand domesticity as this extension from your inner body out to the social life that we live within.

Tatiana Bilbao photographed in the 18th-century Valencian kitchen at the National Museum of Decorative Arts in Madrid. Portraits by Daniel Riera for PIN–UP

KOOZ So beautifully laid out — the way that you describe the affordance of finding accommodation for ourselves at different scales, and with different levels of intimacy.

TB I’ve been dedicating my entire career to this, through academia and the production of projects. The studio at Yale allows me to experiment further on these very topics, and those principles are always embedded in the projects that we do. I think, for example, of the Botanical Garden (2005) in Culiacan, Mexico, as a living room and a dining room — and why not the bedroom as well, we have hammocks! But I also think about the house as a garden, where people create social encounters and a collective environment.

KOOZ I was just thinking about how the domestic realm can become a space of social encounter, and likewise, public space can be a site for intimate exchanges or even solitude. Your studio at Yale has held titles like “Domestic Imaginaries,” “Housing: The Constitutional Right” and “Domestic Realities, Urban Utopias.” I notice that my students are aware of their political role, but they’re also deeply aware of their burdens — financial, ecological, and otherwise. I teach in the UK and you teach in the US, where formal education costs a lot of money. But I do see future generations of architects responding to this notion of care across scales — rather than the house as an object with which to experiment, as in the twentieth century.

"I have never been able to think of architecture as an object […] I have always thought of architecture as a platform for life to evolve and exist and be."

TB I have never been able to think of architecture as an object — in fact, that’s one of the things that, at the beginning, made me doubt whether I was really an architect. I have always thought of architecture as a platform for life to evolve and exist and be. When you think of doing that as an art, it’s a different profession. I use geometry and proportions and materiality as tools for those buildings to exist, rather than as their definitions. That’s also embedded in my teaching; we need to think about the production of space in a very different way — at least, I hope that is present in what comes across. Again, perhaps in previous years I was not talking about care per se, but I think that I’ve always described architecture as a protective structure — or maybe a structure that mediates between us and the ecosystems in which we find ourselves, with which we interact and create our own ecosystems.

Inspired by Diego Rivera’s Man Controller of the Universe, in which a man clutches a machine to command the world, Tatiana Bilbao’s design for the Sea of Cortez Research Center (2023) takes the aquarium as a symbol of that same belief in human domination through technology. But rather than assert control, the project imagines a speculative future: in the year 2289, people stumble upon a mysterious structure built in 2023, long since flooded by seawater and later reclaimed by thriving life. The project underscores architecture’s role in reconnecting humanity with the natural world as a condition for survival. © Juan Manuel McGrath

KOOZ That’s the dream, right? To create a framework in which the occupants can inscribe their own form of life. I wanted to hear about the installation La ropa sucia se lava en casa at National Gallery of Victoria in 2022. My Spanish is not great but that translates to “dirty laundry is washed at home,” right? For me, it speaks to a lot of things, not only about the public-private divide, but also about domestic labor and questions around the contours of the family.

TB Yes. This installation was a commission for the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, and it was done during COVID, so we were trapped inside our houses. There was no way that we could talk about anything other than the domestic labor crisis in which we were living. I don’t think that particular crisis has ever been so clear. Have we really set up a system where certain people have to expose themselves to a deadly virus to be able to get food on their plates? We, the privileged ones, were inside our homes, working online, thinking that’s so hard to manage. I mean, come on. It seems that we have not understood that in order to produce, we first need to exist. I’ve been talking about this forever, and it pleases me that housing is embedded as a constitutional right in Mexico, but the problem is how it operates; you still have to pay and be part of the productive system — which means the social housing addresses very few people, relative to the need. It’s really crazy.

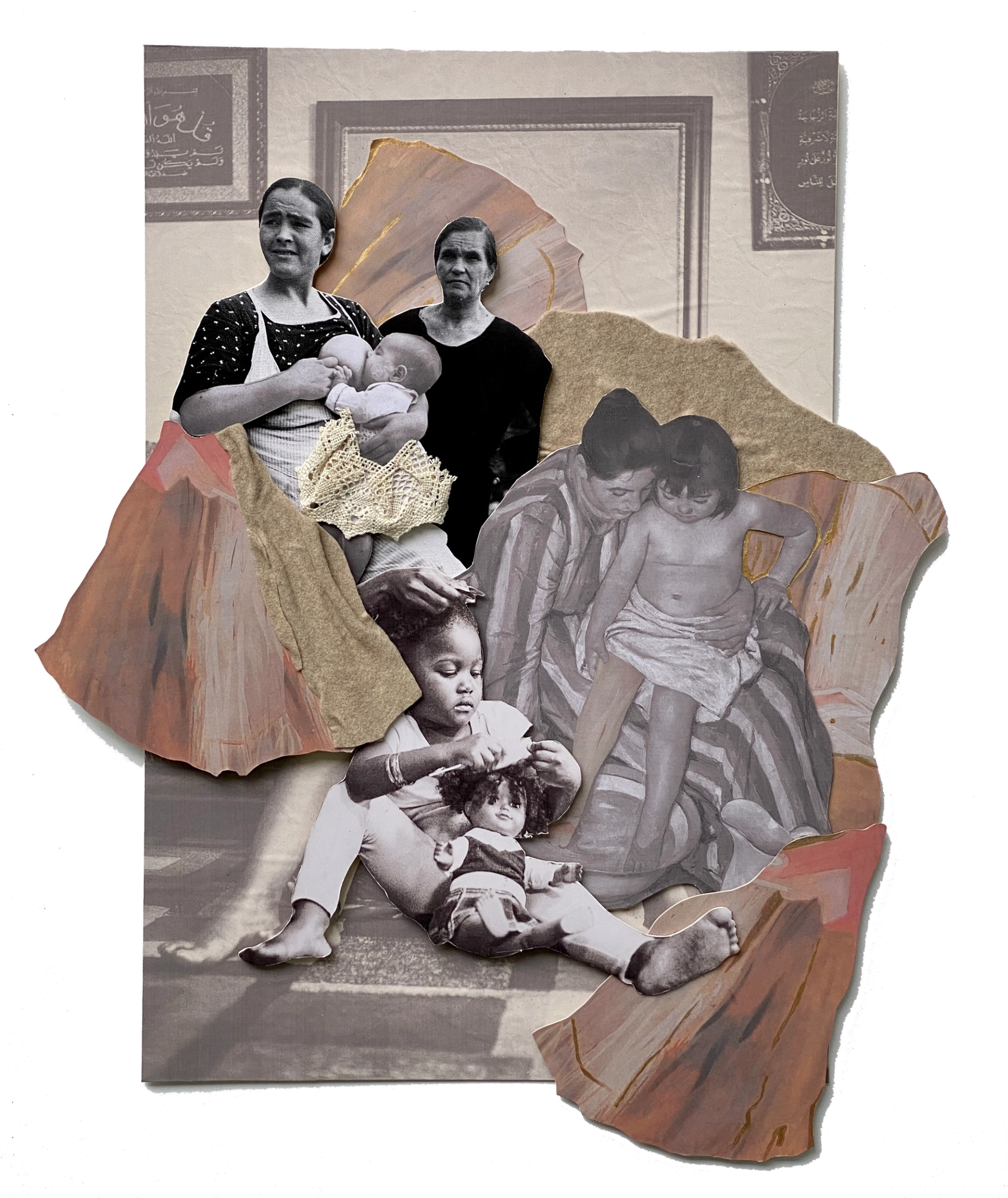

In any case, we couldn’t imagine talking about anything else at that moment, and laundry connected a lot of things. Clothes are the primary layer of protection of our human body, while architecture, we might say, is the second. Secondly, fashion and the production of clothing or garments is a very exploitative industry. When we talk about clothes, we really embed these histories of waste and exploitation. Then there’s the process of taking care of those clothes, which is exactly the same. Who washes them? Who prepares your clothes that enable you to be your productive self? It’s also one of the most accessible ways to talk about reproductive labor. And until recently, laundry was still a public endeavor; it was performed in public. Our installation was a reproduction of a historic site in Mexico for public laundry and washing. We decided to run workshops in different parts of the world, to which people would bring a garment — it could be their own, or something found in the trash, or we would provide them. The idea was that they would pick up a garment and start to talk about who cares for their clothes — or maybe the garment itself, where it came from, who made it, how it got there. As these conversations flowed, we would cut them up and put them back together as large quilts: that was the exercise. So we created these quilts and hangers, which brought together all these conversations so beautifully but also quite literally. On the walls, we added murals depicting the labor of care that is embedded in both caring for and making clothes; the studio also made some collages about that.

La ropa sucia se lava en casa (Dirty clothes are washed at home), installation view, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia, 2022. At its center is a communal washbasin inspired by an 18th-century Lavadero in Huichapan, Mexico, encircled by collaborative textiles created in public workshops in Mexico City, Berlin, and Melbourne. Bilbao reframes domestic labor as a site of care, proposing that the act of washing clothes should be rethought as a shared social ritual. Photography by Kate Shanasy for NGV.

KOOZ The expression “dirty laundry” also refers to secrets, particularly domestic or familial scandals. I love the metaphor of exploding those conservatisms that keep these so-called shameful secrets and contradictions within — tensions that are usually invisible. This is powerful stuff.

TB In Mexico, the phrase “la ropa sucia se laven a la casa,” which was the title we used, also describes an act that is done in secret or obscurely at home, rather than something that should be done in the public realm. So we did want to allude to that.

KOOZ It was really during COVID that I started thinking about the atomization of the nuclear family in the domestic realm. Can we talk about the relationship between domestic architecture and the shape of the family?

Tatiana Bilbao’s Casa Ajijic (2010), built in a small town outside Guadalajara, responded to budget limits by turning to the most abundant material already on site: earth. Four intersecting cubes — two aligned with the lakeshore and two rotated at 45 degrees — created a flexible layout. The earthen walls not only expanded square footage but also provided natural thermal insulation, ensuring the home’s durability. Photography by Iwan Baan.

TB Totally. I think it’s directly linked, and architecture has instrumentalized that diabolical system for sure, 100%.

KOOZ Why do you call it diabolical?

TB Because it is! In Mexico, we didn't live in nuclear families; we lived in villages, as communities that were more connected. We took care of each other. We really believed and understood that to care for a being, you need a village. There are certain architects who think that in designing standardized mass housing, they’re doing a marvelous job by providing places to live. But no, I think it creates places that really ban people from life. I know that there were some very Machiavellian systems concentrated on producing family homes in the United States and specifically in the United Kingdom — enabling the Conservative parties first to keep women in the home. The diabolical part is that society at large is moving to reproduce this system without even realizing it — a system that does not share its benefits with those who need it. And that’s the problematic part. In fact, the constitutional right to housing in Mexico, which I keep mentioning, used to say that every family has the right to enjoy a dignified place to live. It was changed from “every family” to “every person” on 31 December 2024, and of course, I’m very happy about that. The definition of the family itself was removed some years ago in Mexico City — in the city, your family can be you and your dog; you and your three cousins; you and your mother and your grandmother; you and your husband and your children. But that’s not how it works for the whole country, which is still very conservative. So certain people can find themselves enabling or enforcing conditions without really thinking about it, because of where they’re coming from — or because they’re not responding to human needs. They’re responding to political and economic needs.

Collage from "La ropa sucia se lava en casa" at National Gallery of Victoria, 2022

KOOZ Speaking of impositions, I’m also thinking about colonialism — after all, I’m speaking to you as a Mexican woman in Spain. To what extent has the Mexican idea of home been written over by Spanish and American influences?

TB Well, there is a hyper colonial influence. We are very much colored by Spanish influences, and also from the United States — because to refer to the United States as “America” is also colonialism, in a way. Mexico is America too. In Mexico, the “standardized” house is a reflection of colonialism. Our constitution recognizes 67 different types of culture. We are really an array of totally different cultures, that are currently denominated as Mexico — which itself is a colonial idea, because Mexico never existed before. It was created by Spain. Each of these groups had cultures of their own, but none lived the same way. Their social, political and physical ideas of existing on this planet were not similar; their architectural expressions were very different.

Right now, housing is produced in exactly the same way across the whole country. It follows the constitutional law, which describes what a house is and needs to be: literally, a place with a kitchen, a bathroom, and two rooms. That structure is embedded in the law, which means that you don’t have the flexibility or the possibility to express your culture. The Mayans do not have a kitchen inside their social compounds; the kitchen is social, as is the bathroom. You are already eliminating their culture and their way of life by doing that. Before housing became a right, the constitution said that Mexico recognized itself pluricultural and that every culture had the right to express itself. But that idea is already dead in the next line, because you cannot build a house — nor ask for any subsidy or property rights — unless that house fulfills the law.

"In Mexico, the “standardised” house is a reflection of colonialism. […] We are really an array of totally different cultures, that are currently denominated as Mexico — which itself is a colonial idea, because Mexico never existed before […] Their social, political and physical ideas of existing on this planet were not similar; their architectural expressions were very different."

KOOZ This is such an important point. It’s not even about enshrining the past, reifying indigeneity or necessarily advocating for the non-normative family, but rather allowing for a diversity and plurality in forms of life.

Bilbao’s proposal for Xola (2023–ongoing), a mixed-use affordable housing complex in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, diverges from convention by replacing commercial frontage with a six-story art museum. Behind it rises a ten-story residential block with 19 affordable units.

TB It’s about providing the possibility for anyone to exist, and not imposing anything. In Mexico City, we’re bringing the domestic realm to the exterior, to the public realm through the UTOPIÁS project. It clearly invokes the name of utopian spaces, but it's also an acronym which signifies socialism [UTOPIÁS stands for Units of Transformation and Organization for Inclusion and Social Harmony, or Unidades de Transformación y Organización Para la Inclusión y la Armonía Social]. The project is about holding space for domestic labor into the public realm — space to care for people, to care for people that care for people. They have open-access services like kitchens and laundries, but also workshops, sports and culture programs, elder and child care, even health services.

"The project is about holding space for domestic labour into the public realm — space to care for people, to care for people who care for people."

KOOZ As we’ve been talking about domesticity, I thought I’d wrap up by asking about the holiday home that you’re in now — is it yours or rented? What are some of the things you do to make it feel like home?

TB Well, this is not my home. This is a house we rent in Galicia, and this is the fifth year that we’re coming here — the fifth summer. I don’t do that much to make it my own, but there is one thing that is actually mine in this house, and it stays here. It is only pulled out when we come.

KOOZ What is it?

TB It’s a blender! I bought it here to make my breakfast; we use it a lot in Mexico — to make all the salsas, the juices in the morning, things for kids. So apart from the things that we pack, this blender is the only thing of mine here. I don’t feel any ownership of the house, but I’m very comfortable here. We considered staying in another beautiful spot nearby — but I felt funny about it, like we’d have to come here as well.

KOOZ I form attachments to places very quickly too. Ownership is not the right word. It’s more like spatial attachments. It’s amazing how quickly that happens.

TB Yeah, totally. But then I often think that home is my family…

KOOZ So wherever they are is home?

TB Exactly. Also because I’ve lived in the same apartment for almost 20 years; for me, having that “home” has been a very steady base. I travel so much — really, a lot. I don’t know if I have any rituals, but when I arrive somewhere, I like to really install myself. The moment I open the door, I hang up all my things; it doesn’t matter if I’m only there for one day. I take my toiletries to the bathroom, I put my clothes in the closet. I like to feel that I’m really there.

About

Tatiana Bilbao ESTUDIO is a Mexico City based architecture studio, founded in 2004. At the core of the studio's practice is an analysis of the context surrounding projects, which scale from masterplans to affordable housing strategies, from city planning to furniture design.

Bios

Tatiana Bilbao is an architect and the principal of Tatiana Bilbao Estudio, which she founded in 2004. Prior to this, she was an advisor in the Ministry of Development and Housing in Mexico City. She also co-founded an architectural think tank, Laboratorio de la Ciudad de México, and an urban research center, MXDF. Bilbao holds a recurring teaching position at Yale University School of Architecture and has taught at Harvard University GSD, Columbia University GSAPP, Rice University, University of Andrés Bello in Chile, and Peter Behrens School of Arts at HS Dusseldorf in Germany.

Shumi Bose is chief editor at KoozArch. She is an educator, curator and editor in the field of architecture and architectural history. She is a Senior Lecturer in architectural history at Central Saint Martins and also teaches at the Royal College of Art, the Architectural Association and the School of Architecture at Syracuse University in London. She has curated exhibitions at the Venice Biennale of Architecture, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal Institute of British Architects. In 2020 she founded Holdspace, a digital platform for extracurricular discussions in architectural education, and currently serves as trustee for the Architecture Foundation.