Italian prisons are in a state of emergency. In 2013 Italy was condemned by the European Court of Human Rights for inhuman and degrading treatment. Despite attempts at reform, problems of overcrowding, inmates’ distress, and inadequate facilities persist. This critical situation has been further intensified by the Covid-19 pandemic, which has caused riots and suicides. In such circumstances, architecture can intervene tangibly by modifying the spaces. Furthermore, it can fulfil its social role by raising awareness of the need for prison-focused projects.

Our research established a participatory process inside Milano-Bollate Detention Centre prison, an institution recognised for promoting inmates’ reintegration and rehabilitation. The design proposals aim at revealing the potential of underused spaces inside Italian prisons, through sport and physical activity. Among possible investigation themes, sport-based interventions are interesting because they provide multiple physical and psychological benefits.

The methodology emphasises the research through people, which collects stakeholders’ needs and feedback, thus advancing further the design process. The interaction with the community is essential to make the project a shared modification of spaces and practices. Therefore, we gave prominence to the communication aspect, keeping track of the research process through diagrams, timelines, and illustrations.

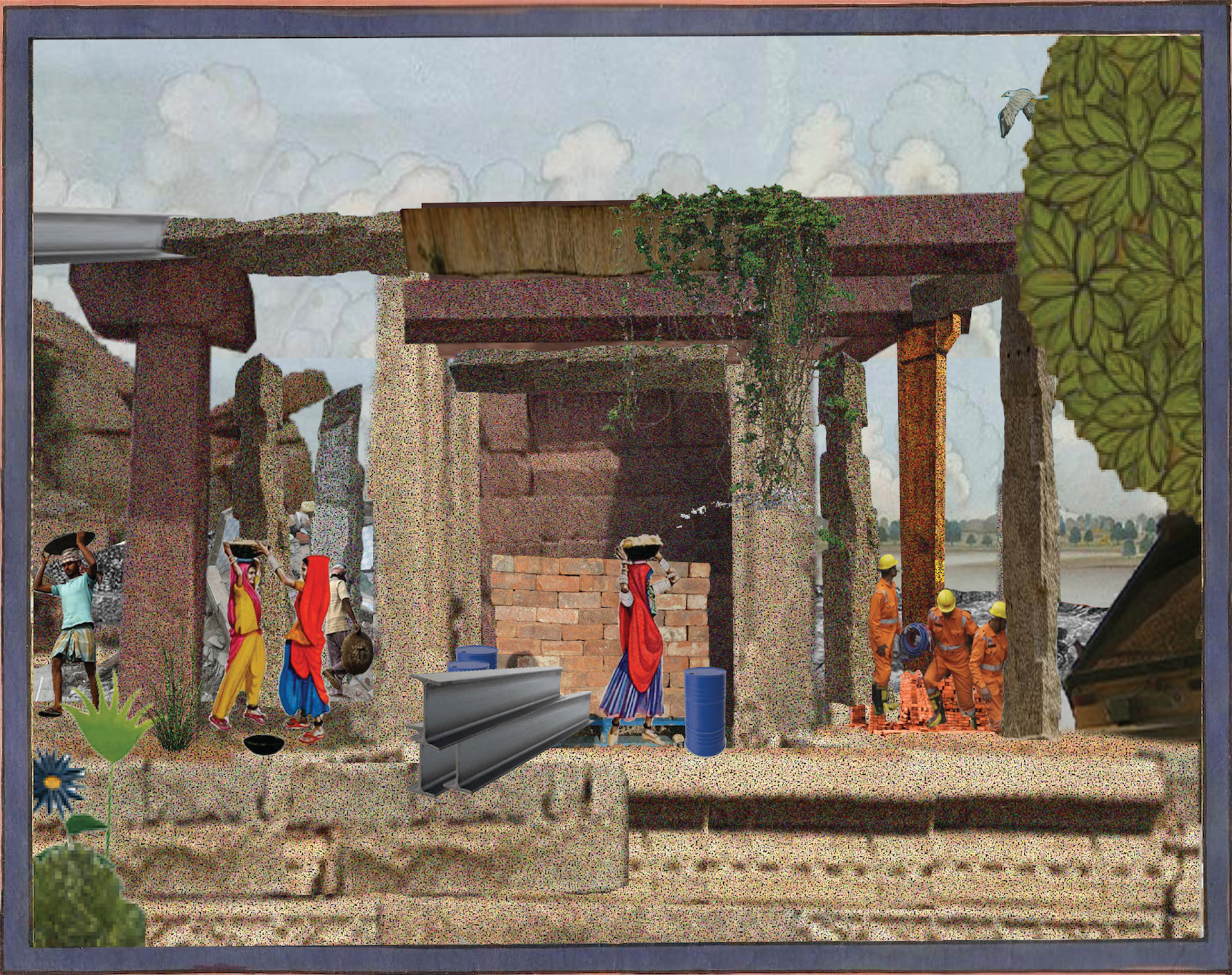

The context analysis led to the drafting of architectural intervention proposals for Milano-Bollate Detention Centre spaces. The masterplan envisions how the institute can be transformed through sport, not only in terms of spaces refurbishment but also new practices introduction. In particular, we investigated the courtyards. These outdoor spaces are very easily accessible but inadequate for sports practice. The design approach is based on actual feasibility. It keeps the existing architectural structure, to comply with the current surveillance regime, as discussed with the prison administration. Sports spaces are conceived as multipurpose public spaces for aggregation and socialisation. The design includes new equipment, sports fields and a renovation of all surfaces with suitable materials.

The case study typology is recurring among Italian prisons. The proposed strategy could be applied to other institutes with similar features. Overall, the impact of the research process lies with the analysis of the requests from the inhabitants combined with context-specific features, as well as social, historical, and normative issues. This attitude is especially relevant when architecture is confronted with fragile contexts, where local resources and solutions should prevail over authorship. Acting with this awareness means restoring architecture responsibility to propose a change, especially in marginal contexts such as prisons.

The project was developed at the Politecnico di Milano, Italy.

In 2013 Italy was condemned by the European Court of Human Rights for inhuman and degrading treatment.

KOOZ What prompted the project?

FS | SS | FV Our research on detention spaces started two years ago, through a participatory project inside Bollate Detention Centre in Milan. We decided afterwards to develop this work further, exploring the theme of sport in prison. Sports spaces are interesting for their non-hierarchical features, as they allow inmates more freedom of movement and more opportunities to socialise. The beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic aggravated the flaws of Italian prisons, such as overcrowding and inadequate facilities. At the same time, this situation forced some long-due changes, namely the use of Internet for communication with the outside world. This allowed us to reconsider our work method. For instance, we were able to hold interviews and brainstorming sessions with inmates through video calls.

KOOZ What questions does the project raise and which does it address?

FS | SS | FV The project acknowledges this context limitations and society unawareness of prisons condition. It raises questions such as prison architecture influence during the detention and towards reintegration. This process is complicated because interlocutors have limited possibilities of choice concerning their living environment. The participatory design investigates inhabitants empowerment in time and space management. In this sense, the project faces multiple issues, such as how to restore inmates self-determination or how to interact with stakeholders to recognise different needs and goals.

[...] the project faces multiple issues, such as how to restore inmates self-determination or how to interact with stakeholders to recognise different needs and goals.

KOOZ How does the project approach the prison as a typology and as an institution?

FS | SS | FV The spatial structure of a penitentiary is representative of the power relations within, as well as its role in society: the form truly embodies social interactions. In this sense, typology and institution reflect each other. Bollate’s tree typology is one of the most common in prison architecture, both in Europe and the United States. It has a rigid structure that constrains movement choices: the only possible movement is back and forth, along the arms and the distribution corridor. Since this typology is so diffused, its analysis can generate considerations that can be also applied to similar contexts, thus proposing a research tool.

KOOZ What case studies did you look to as references? How did these inform the project?

FS | SS | FV The case study analysis was important at each stage of the research. Regarding the spaces of detention our main source of inspiration has been LAN (Minimum Security Prison, Nanterre), and Archivolt with Petra Blaisse (State Penitentiary, Nieuwegein). Their attention to open-air spaces design and use of unconventional colours and materials influenced our sports design aesthetic. Regarding the narrative of the participatory design process, our references were the research on Lieux Infinis by Encore Heureux, the sensitive maps by Raumlabor and the illustrations by Isabel Gómez Machado. These references enabled us to communicate interactions with stakeholders and convey personal feelings and impressions.

KOOZ What are for you the greatest shortcomings within these spaces?

FS | SS | FV In Bollate there is a general lack of sports facilities. Therefore it is difficult to guarantee access for all and shifts have to be made. The few spaces that do exist are not designed for sport: they are mostly empty and without equipment. They are visually limited, offering a grey and monotonous experience, with no colours nor greenery. The prevalent materials are hard surfaces, such as concrete and asphalt, inadequate and dangerous. These problems are worsened by poor maintenance and management problems related to the lack of staff to run the activities.

KOOZ How does the project address these?

FS | SS | FV On a masterplan scale, the strategy is to increase sports spaces by refurbishing existing spaces and introducing new ones. The architectural design focuses on sports dimensional and infrastructural needs, as well as spatial compatibility between different activities. The aim is to offer a variety of possible sports with a minimum investment, through multipurpose and versatile facilities. Sports spaces are conceived as socialisation and leisure places, which do not exclude those who are not interested in sports activities. Furthermore, the design intention is to differ from the prison aesthetic in terms of colours and materials, displaying a shift in detention spaces conception.

The project raises a reflection on the role of the architect in co-designing detention spaces [as] a mediator between all the stakeholders.

KOOZ How does the project approach the role of the architect and the power of architecture?

FS | SS | FV The project raises a reflection on the role of the architect in co-designing detention spaces. In this process, the designer becomes a mediator between all the stakeholders. The architect plays a broader role because he encourages people to become aware not only of the critical aspects of the space they inhabit but also of the motivations behind them. Then, starting from the real needs and expectations of the community, the designer can outline new possibilities for transforming the territory and its uses. This concept echoes Giancarlo De Carlo’s theories. An idea of architecture that aims to answer concrete questions and not to envision top-down models. The power of architecture lies in materialising change. When realised, new spaces generate new uses, new habits and thus a general transformation.

KOOZ What is for you the power of the Architectural Imaginary?

FS | SS | FV We believe that architecture has a universal language and therefore offers a commonplace for dialogue between all inhabitants, inside and outside of prisons. Indeed, during the interactions inmates have taken images or elements of the project and spontaneously constructed other intervention possibilities.

The power of Architectural Imaginary lies in offering visions that inspire change and allow people to express themselves, recognise themselves in the space they live in and thus self-determine. Whereas change cannot materialise, due to lack of political will or funding, Architectural Imaginary can still raise awareness of the need to address fragile contexts.

About

Fabio Samele, Sara Spiriti and Francesca Varotto are three Italian architecture graduates from Politecnico di Milano. Their work together involves research on social architecture, urban regeneration, and participatory design in fragile contexts. They studied in France, South America and Spain and they share interests in graphic design and storytelling.