When the pillowy-white swathes melt from Tyrolean slopes, and the ‘snow toys’ are tidied away like so many toys, the scar tissue of a ravaged mountain environment is revealed. Thus begins the labour of territorial modification and aggressive beautification, in order to restore and develop the unsustainable economy of ski-monoculturalism. As the winter seasons shorten, considerable resources are required to maintain the pristine environment expected by those who seek pristine and powdery runs. Beatrice Citterio shares her reflections upon studying the ‘liminal space’ between tourist seasons in the South Tyrol region of Italy.

KOOZ Liminal Spaces. A Visual Exploration of Skiing Between the No-More and the Not-Yet, that you developed within the context of the University of Bolzano, explores the intricate relationship between ski monoculture and mass tourism, focusing explicitly on mountain regions. What prompted the project?

BEATRICE CITTERIO When I moved to Bolzano after more than twenty years of living in Milan, I did not expect it to have such an influence on my way of observing and interpreting relations between humans and non-humans, or between humans and places, but I slowly began to realise that something in my perception was changing. South Tyrol is a region with a very high rate of tourism, and this can be seen daily by the crowding of specific focal points in the city or renowned valleys such as Val Gardena. I was used to skiing since I was a child, but living in the midst of mass ski tourism prompted me to investigate this reality in greater depth. Observing the interrelation of temporary mountain tourism to the plains and cities, and relating this to the state of the art of ski tourism in the region, I was moved to interrogate a system so deeply rooted that it would seem impossible to imagine an alternative.

It was also a way to reach a deeper understanding of a region like South Tyrol — frequently misunderstood by the rest of the country but, at the same time, highly exploited for winter and summer vacations. Since I started working on this subject, the newspapers have been full of news about the area: climate change, artificial snow, red accounts related to COVID-19 shutdowns, and much more. That's when I realised how urgent it was to discuss this issue. I began to question various experts in this field in the region, including some politicians, and I came into contact with the definition of 'ski monoculture' and its economic, social and environmental implications. Then, I became familiar with Marc Augé’s definitions of the terms 'place' and 'non-place' and felt that this was a key lens of interpretation around which I might develop my project.

KOOZ Liminal Spaces emerges as a study into the period in between the high season winter and summer months, when the mountain wounds emerge as the snow progressively melts and the snow toys are put away. As an architect, what tools did you deploy to map and analyse the liminal territory between the 'no longer' and the 'not yet'? How do these tools unravel the canons of beauty and attractiveness that have characterised the commercialisation of the mountain environment?

BC I began by observing everyday things around my home during the Christmas holidays: the flow of tourists, mobility, openings and closures, things like that. This was accompanied by a thorough investigation of newspaper articles about the seasonality of ski tourism — I found and conducted interviews, visual archive research, studied flows through installations in the field and via satellite, and participated in conferences and dissemination events. These steps helped me to investigate the tools through which mass tourism has been consolidated from the 1950s until now: advertising, postcards, illustrated images, slogans, paper maps, interactive maps, photographs and videos. Indeed, these became the very tools I wanted to use in my communication — I considered it necessary to use a language that was not too distant from the current one but which had a critical, though not too violent, function.

Ultimately, photography and georeferenced satellite mapping were the main tools for research and dissemination. Photography turned out to be one of the main tools as it was my primary means of documentation during field trips of investigation and discovery. It allowed a static image of a temporary situation to be made eternal. Georeferenced digital mapping via satellite was indispensable: on the one hand, to support the quantitative visualisation of the numbers linked to mass skiing (and which are often ignored), and on the other, to graphically evidence the man-made modification of the terrain, through satellite photos taken over time. The narrative becomes clear when depicting this material in correspondence with the sites with the most significant tourist density, incorporating qualitative and quantitative data into a single output and giving back identity to places that are often known only by name or in photos.

KOOZ Throughout the project, you also engaged with initiatives as the organisation POW (Protect our Winters), amongst others. Could you expand on the voices you engaged with when undertaking the research and how they informed the research?

BC My journey with POW (Protect Our Winters, Italy) started at the beginning of the project; the enormous support that I’ve received from POW has allowed me to get in touch with and, in some cases, interview people who are experts in the field or in some way involved in the winter sports discourse. These include members of environmental associations and collectives, writers, journalists, athletes, worried and angry citizens, climatologists, activists and politicians, through official meetings or public events, including public protests, book presentations, festivals and more.

The contribution of POW to the research has been vital for two reasons. Fundamentally, it gave my project real dimension, deepening my daily understanding of the place to an unimaginable degree; in addition, they helped me focus on the current need for communication and dissemination. Furthermore, it has given a community dimension to a problem that truly concerns an immense geographical and, above all, social territory. Such problems can be difficult to tackle due to insecurities linked to the size and power of established systems — especially in a region like South Tyrol where, as I learned from the people I met, those who criticise these issues are notoriously frowned upon.

Being afraid to change is an inherent characteristic in human nature, but precisely because we are part of the nature in which we live, we have the strength to adapt, and perhaps the time has come to face reality and act accordingly.

KOOZ To what extent has all this — the convergence of climate change, aggressive land-use practices, disproportionate development of mobility systems and the consequently unsustainable tourism models — affected the delicate balance between economic prosperity and environmental conservation? Did this balance ever exist?

BC I think the point of all the environmental discourse should be seen not only from the sake of the environment but from the perspective of our own future survival. This is what I would like my project to emphasise: namely, that the subjugation of nature to our needs to such an extent that we emulate some of its manifestations — to perpetuate practices such as skiing in this case, and thus the development of adaptation techniques such as artificial snow — is merely a postponement of the realities that we will have to face sooner or later. The earth has seen it all, and it is not the main reason we need to change our attitude.

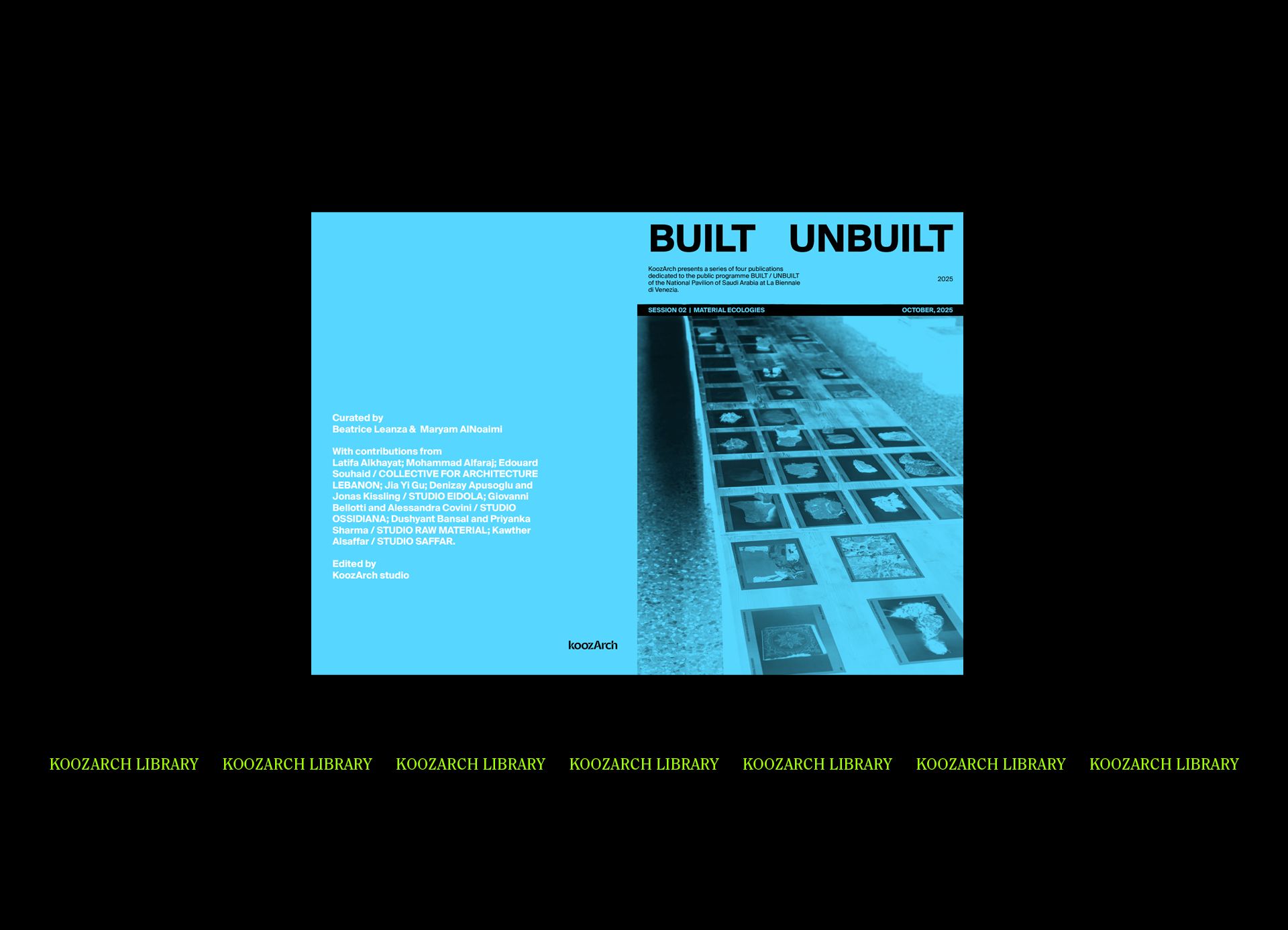

Beatrice Citterio, "Liminal Spaces. A Visual Exploration of Skiing Between the No-More and the Not-Yet, January-July 2023. Photo by Beatrice Citterio.

If talking just about my project, the balance between human activity and the environment has been put to the test since the birth of the first resorts for mass mountain tourism, as seen in the French model of the 1960s. The difference between then and now is that the climate forecasts, the extraordinary weather events we are witnessing, and the critical situations we find ourselves in every year (e.g. droughts, fires and more) require us to take a broader view of the places we live in. At least, they suggest that the view we have had up to now has been too narrow: we can no longer afford to think in a segmented manner, rather we need to systematise the causes, effects and consequences of our actions in the long term. I think that the key to our survival lies in the care we take of ourselves, those around us and that which is more-than-human around us — this also includes the ecosystems we are a part of, those we disturb and even those that backfire on us.

In the case of mountain tourism, an aggressive focus on winter sports and intensive tourist use, must be viewed according to the priorities that we as human beings decide to set in facing future realities: where will we live when temperatures on the plains are intolerable? What are the values according to which peaceful coexistence might or could be possible in times of tension and deprivation? This is where balance, respect, moderation and sharing come in; elements that have always been part of mountain culture but which have been put on the back burner for profit or out of inertia. Being afraid to change is an inherent characteristic in human nature, but precisely because we are part of the nature in which we live, we have the strength to adapt, and perhaps the time has come to face reality and act accordingly.

KOOZ The key component of the research comprises a photographic project on seven ski areas at the end of the ski season, conducted between April and May 2023, which reveals that although the snow has melted, the groove of the snow corridors remains imprinted in the alpine slopes, delimited by forest lines, snow cannons, service pylons and ski stations for ascending and descending, bridges, footbridges, canals, tunnels and concrete slabs, perennial traces of the infinite modifications and corrections practiced on the terrain.” What is the value in unveiling these “disassembled circus” and posing the poignant question of whether this is all worthwhile for a rewarding descent?

BC During the research phase, I found it difficult to imagine how I would communicate the nuance of these intertwined systems to an audience unfamiliar with this place. Then, I thought of the benefits of taking an oblique point of view: in fact my goal was to start a discussion without necessarily revealing everything I had found. So I asked myself: if until now I have investigated the ‘solids’ — that is to say, only looking at the representations of the high season — what do the voids look like? What about the period in which the aestheticisation of the mountains is lacking: could this draw attention to the issue? So I started to take these photos, which testify to the intense labour of aestheticisation being done on the mountain environment, and whichreveal a number of features that characterise mass tourism: seasonality, intensity, modification of the territory, commodification and anthropisation, depopulation, cultural and environmental flattening, loss of identity. On the other hand, they simultaneously serve as evocative artefacts of a reflection that goes far beyond the subject matter. They represent that not everything is forever; that we often only see the superficial part of a system that, in reality, has many flaws of which we are unaware due to ignorance or a lack of information. Sometimes, even if we have access to the information, we ignore it. If we put the evidence we see in the photos into the system, and study this against the level of public funding, high costs for users and the narrow band of customers that can afford to ski, we reveal what I have sarcastically expressed as a scale ofdescending rewards. The question therefore becomes one of elitism, accessibility and management of both public funds as well as natural resources.

There is a lot of work to be done, and I would like my project and its possible extensions to help catalyse a process of transition — which will, unfortunately, be very long and full of resistance.

KOOZ The premise of the thesis is that it is a “work in progress”. How do you imagine and seek to continue to pursue this research in the coming months? What might be your ultimate objective?

BC I think that the implications of this project could be varied in several directions, both locally and continuing to raise awareness among the tourist and temporary public. I am already in contact with many organisations to bring this exhibition to the broader public, both in the city and in the mountains — this will keep me busy for several months. In the short term, I have lots of ideas, including an extension of the photographic project and on-site interventions concerning abandoned or temporarily closed ski resorts. These projects could bring attention to the issues of weather and climate change, and of maintenance or the absence of care. In the long term, I would like the combination of these sub-projects and citizen participation actions to have an impact at a higher level and thus be able to influence the course of investment and decision-making, even in a small way. I like to call the project a 'work in progress' for this very reason: there is a lot of work to be done, and I would like my project and its possible extensions to help catalyse a process of transition — which will, unfortunately, be very long and full of resistance.

Bio

Beatrice Citterio was born in Milan in 1997, where she completed her Bachelor's degree in Industrial Design at the Politecnico di Milano. The pandemic led her to move to Bozen, in the middle of the Italian Dolomites, where she studied and graduated with Masters in Eco-Social Design from the Free University of Bolzano. The leap between the large metropolis of Milan and a much smaller city like Bolzano, immersed in a highly touristic region, led her to observe the human and more than human relationship mechanisms more analytically and critically. This led her to develop her master’s Thesis research on mountain tourism and its consequences on the territory, its ecosystems and socio-economic layers. In both research and shaping the outputs, her work focuses on visual communication tools such as photography, video and interactive mappings and growing digital practices such as 3D scanning and multi-scale visualisation tools.