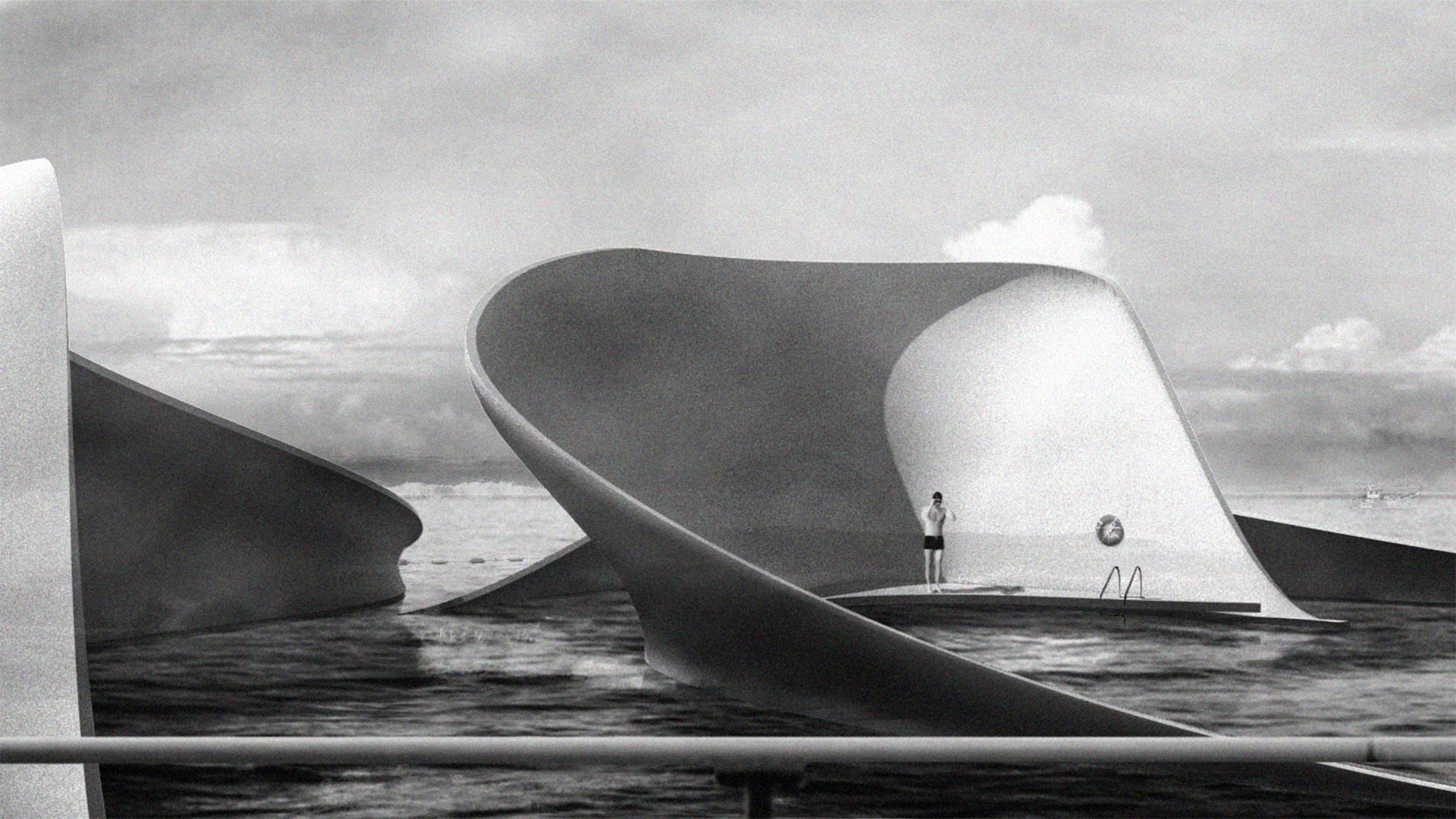

Stemming from an experiential passage of a WW2 fortification by W. G. Sebald in his novel Austerlitz, the project’s underlying thesis was built upon military architecture’s relationship with its surrounding landscape, specifically how it calibrates the coastline in order to command it, and how the landscape transforms in relation to such interventions. The contemporary translation of these historic networks of defensive architecture, studied through the eyes of Paul Virilio in his book Bunker Archaeology, brought to bear a modern attitude towards the authorship of the shifting landscape and the passing of time in the creation of structures and spaces.

The natural and biological forms of the proposed landscape responded to the monolithic nature of military fortifications through the utilisation of ferrocement construction – known to some as the predecessor to reinforced concrete and often used in boat hull construction for its thinness, flexibility and strength. Adopting this approach allows the architecture to converse deeply with the natural context, but also becomes environmentally conscious in its minimal use of material, suggesting that we may find strength in natural forms rather than in brute thickness. The research and sensibility of bunker architecture was relocated to the Cornish coastline in the south of England where, throughout my life, I have witnessed the erosion and degradation of the unique dune systems that span the edge of the land. In response to the immediate threat these habitats face, the attributes of defensive structures were developed and applied to a specified dune environment, enabling a consequential and incremental reconstruction of the landscape and thus serve sustainable, cultural, and societal uses for the long-term existence of Cornwall’s vital inhabitation and accessibility of coastal communities.

The authorship of time and landscape is acquired through a consciousness within the design process to anticipate the incremental movements between the man-made and natural. The further we deepen this connection, the further we may benefit from both the protection of dune habitats and the social and cultural functions of its adjacent community. It is by understanding the natural formations of landscapes that we will have the largest impact using the smallest footprint. In the passing of time, both man and nature become the singular author of a subsequent landscape.

The project was developed at the Queen’s University in Belfast.

KOOZ What prompted the project?

JM The project took its starting point in a deep fascination with landscape and time captured through many years photographing the Cornish coastline. In first taking a passage from the novel Austerlitz by W. G. Sebald, the architectural influences began by studying the defensive fortifications that span the Atlantik wall: an unprecedented network of coastal interventions built during the Second World War and documented in detail by Paul Virilio in his book, Bunker Archaeology. The research developed into a series of studies documenting the geometrical rigour of military architecture, specifically the way in which they calibrate and control the landscape that they command.

This sensibility of architecture and landscape was then applied to the coast of Cornwall, the environment in which I am personally familiar and have witnessed even in my lifetime the fragility and transitional nature of the coastal landscape. Particularly in Cornwall – a place driven by tourism and natural beauty – the downward turn has been enacted by a misalignment of our unsustainable footprint and the finite world in which we live. It was from these themes that the unusual parallel was drawn between the function of military architecture and the unidentified strategies we require to protect coastal landscapes.

The authorship of time and landscape is acquired through a consciousness within the design process to anticipate the incremental movements between the man-made and natural.

KOOZ What questions does the project raise and which does it address?

JM Constructing a Landscape in Time firstly questions the authorship of an intention to design and build in the landscape. My design process thrived by adopting a flexible degree of modesty that has required me as the designer to engage with the natural formations and consequences of the coastal environment. The interventions, whether it is a foundation, wall, or roof, work strategically in collaboration with the transitional surfaces upon which they are sited. Often, we design with a vision of the moment of completion, however here the project engages with the notion of time and anticipates the consequences imposed by the environment infinitely beyond its realisation. The building is then considered to be built by both architect and landscape. It is this co-authorship that is proposed to reverse the unbalanced relationship between us and the land which has led to conditions such as that at Porthtowan dunes where the proposed scheme was sited.

The project also contributes toward a conversation of materiality, in which one may question the use of concrete within a proposal that has an environmental conscience yet finds its influence in the brutality of military architecture. The early research in response identified ferrocement construction as a method used to minimise the weight and thickness of concrete by using layered wired mesh and applying a cement mix once the form as been created. This method is most popular in the construction of boat hulls but has also been used historically in architecture. It can be seen in Pier Luigi Nervi’s Orvieto Hangar and Felix Candela’s hyperbolic paraboloid structures, both of which find strength in form rather than thickness. The ferrocement concept does however create conflict when dealing with the effect of time in the harsh coastal environment. I believe an architect must consider the lifespans of materials when working sustainably, understanding the rapid structural decline of timber as opposed to a longer lasting material such as concrete. It then becomes a decision of functionality in identifying the purpose of the intervention and what is the right material to form a sustainable condition.

The most potent reflection that I had when looking back was about my attitude towards time and architecture. The decline of these structures when left in nature’s hands is somewhat poetic and gives the same feeling as when we visit protected ruins of military architecture. I wonder whether it should truly be our intention within the built environment to make materials that refuse to age, or will this only detach ourselves from the landscape further?

KOOZ How does the project challenge the potential of re-exploring WWII military architecture today?

JM Military architecture, specifically the bunkers, do not only have functional qualities that I believe we can re-visit, but they are also artefacts of memory and time. Understanding the concepts of memory and time in architecture is mostly about accepting that we are not the sole authors of space. Military structures are built for a very specific purpose at a very specific time, and what we see in the inevitable ‘ruin’ is the effect of age and the authorship of nature as they transform the structures appearance and surface. This project draws from this otherwise neglected role that the bunkers have played silently to this day: orchestrated by function but with a clarity in their ever-changing relationship with the surrounding landscape. A defensive structure is optimised to measure and control a landscape, but in doing so becomes a tool for us to measure time and intervene in the natural transformations that occur inevitably.

The idea is to adopt an awareness of those contextual relationships that are very much alive between interventions and the landscape. I have analysed this with an intention of constructing a landscape sustainably and embedded the notions of movement and time within the design process. This is something that I believe has the potential to reconfigure how architects and users alike view the natural world, no longer as a neighbour but as an author of the spaces we inhabit.

KOOZ How does the project approach the relationship between architecture and landscape?

JM It approaches it in a way that considers architecture as the product of many authors, a conversation between the architect, ground, wind, rain, time, and many others.

One of the things that I am grateful to have learnt during the design process, was an awareness towards how we consider the environments role in the spaces we create. It was often said throughout tutorial discussions that we as designers must allow nature into our buildings to become authors of the space. It is an ideology that this project adopts in quite an extreme sense. In the wider profession, as our materials and technology have progressed, architecture has become about creating defensive structures in which the outside environment cannot alter – essentially a rejection of its authorship. If we are in need of the natural world to help us survive, we must surely reconsider this unbalanced relationship and propose ways in which we can function in harmony with the landscape and all its beautiful consequences.

I am only one person and a young one at that, but the relationship between architecture and landscape is a vital conversation worth integrating into our design processes, especially when dealing with sites such as Porthtowan. Constructing a Landscape in Time was always developed within this discussion, and it will hopefully continue to develop in the future.

Understanding the concepts of memory and time in architecture is mostly about accepting that we are not the sole authors of space.

KOOZ What are for you the opportunities which can derive from a better understanding of sustainable design strategies?

JM As with any movement in architecture the opportunities seem infinite, and there is an excitement for what is to come. Though there are advancements being made in the performance of buildings for example, I believe that we remain far from the turning point.

For me, the single, most important opportunity that understanding sustainable design strategies offers us, as the architect, is a better experience of life for everyone. To consciously refuse the consideration of these strategies is to let down the profession. Our role is to serve and provide for the user, which as an intention does not particularly align well with the headlines that we see more and more highlighting the built environment’s carbon footprint. Failing this understanding, each design that does not consider sustainable strategies will be remembered for their contribution to the decline of the natural world.

KOOZ What is the power of the architectural imaginary?

JM As with the timing of my Masters degree, which like a lot of other students meant that we were not able to see tutors or share our work in person, the presentation and communication of the work became even more important. This enabled me to learn that everything must derive from the project’s intention, meaning for example, to draw a section not because it is conventional but because the investigation of your work demands that you do it.

The architectural imagery created during this project is entangled within the design process in which I was working. I would not say any of the imagery is finished as it tries to consider the notion of time, that the transitional nature of the landscape will continue beyond my interventions. That is why the animated GIF’s were a suitable medium, they document the relationship between architecture and landscape in increments and without end. To have these animations alongside documentations of physical sand castings on the beach only reiterated the idea of constructing a landscape in time. Even in the 3D visualisations of the proposal, it was important that they captured multiple strands of time like the movement of the tide or the slower transition of the structure as the landscape formed around it. That is the beauty that we see now in historical structures such as those across the Atlantikwall.