Lee’s Hard Labor, Soft Space: The Making of Radical Ruralism, and Sattler’s Trembling Worlds analyse questions of land property and productivity in the Upstate New York and Austrian territories and how they inform social identity, memory, and racial issues. Through field and archival investigations, they tackle academic research methodologies, building a critique of capitalism and looking at new cohabitation models.

This conversation is part of KoozArch's issue "Terra Infirma."

VALERIO FRANZONE / KOOZ Your research shares several similarities. Stephanie’s Hard Labor, Soft Space: The Making of Radical Ruralism, and Philipp’s Trembling Worlds deal with the ownership of farms and agricultural lands, a fundamental topic regarding the extraction of resources and production of goods in capitalist systems. Can you introduce your work and your perspective?

STEPHANIE KYUYOUNG LEEMy current work centres on land-based projects — such as farming cooperatives — that focus on land sovereignty in rural settings. In the United States, for example, land ownership and agriculture are inherently rooted in a historically violent dispossession of Indigenous populations and the vast settler colonial project enabled by that deracination. This great displacement, of course, was followed by industrialised trafficking of humans for agricultural production on the same land. The American South and prairie were thus transformed into a colonial experiment in global industrialised agriculture and labour — one that was sold across the Atlantic as a utopia for European farmers. I look at the legal and structural frameworks surrounding and supporting this, including the Homestead Act, the Jeffersonian grid, Alien Land Laws, and various militaristic interventions — historical precedents for land grabs we see in Palestine today — that institute scorched earth policies based on the destruction of livestock, fields, infrastructure, and food supplies. With this history in mind, I refocus the lens to better understand collective approaches to ruralism rooted in abolition, ideas of liberation, and restitutive land reparation.

"In the United States land ownership and agriculture are inherently rooted in a historically violent dispossession of Indigenous populations and the vast settler colonial project enabled by that deracination."

- Stephanie Kyuyoung Lee

PHILIPP SATTLERI'm looking at the history of violence operating through the development of the concept of soil and land and how it articulates property and planning laws in Austria. This work spans from the Imperial 19th century through National Socialism, into contemporary rural landscapes, and focuses on the transformations of agricultural practices and spatial morphologies, to understand the impact of ‘Blood and Soil’ politics and the conceptualisation of soil as integral to property and agriculture. I also analyse soil as an environmental history of architecture, and trace how transformations in agricultural practice are prescribed through changes in the legal sphere.

KOOZ How did you get interested in these topics?

PS A part of it is, of course, personal as with most research. Some of my relatives are farmers and I grew up in an Austrian rural setting in a region that is shaped by historically shifting borders with Italy and Slovenia. In Austria, about 80% of land owned is agricultural, including agro-forestry. Still, access to agricultural land is mostly limited to Austrian citizenship, resulting in exclusive and racialised ownership. As I later began to work on the history of fascism and specifically a memorial project on the labour and concentration camp Aflenz an der Sulm, I understood the strong ties between Nazism and how the reframing of agriculture informs an attitude, pride, and cultural representation of the mostly large-scale farmer as a strictly classed form of pseudo-gentry. From this, I started to understand the development of post-WWII conservative and right-wing narratives and their impact on the fabric of contemporary society, its discrepancies, and began to look at how this legacy can be unravelled through following legal and spatial continuities and changes.

"In Austria, about 80% of land owned is agricultural, including agro-forestry. Still, access to agricultural land is mostly limited to Austrian citizenship, resulting in exclusive and racialised ownership."

- Philipp Sattler

SKL I spent time between Nebraska and South Korea as a teenager, developing a transnational identity. The rural landscape of Nebraska is highly gridded, mono-cropped, vastly industrial, and flat. The legacy of erasure felt oppressive and physical. Part of my stake is locating the alternative history to this manufactured landscape and creating a different understanding of the bucolic American prairie life and its Western cowboy narrative. For example, I locate emergent ideas from early abolitionist communities, as well as groups from the civil rights era and feminist movements. I frame this as a project of radical ruralism where I resituate the American countryside as a site of escapism, of cultic decamping, and collective experiments.

KOOZ Stephanie, your case studies revolve around multiracial communes and commoning practices; on the contrary, Philipp, yours is about racial supremacy. Can you tell me more about the historical and ideological background of your researched models?

SKL The Homestead Act created a 270 million acre colonial agro-utopia somehow based on commons and pietist principles that redistributed land primarily to European white settlers. Timothy Miller, a religious historian, defines the history of U.S. settlement as continuous spurts of communes and intentional communities.1 Similarly, Dolores Hayden and Oswald Mathias Ungers were interested in cataloguing the spatial language of various utopian communities across the U.S.2 In response to these accounts, I trace the intersectionality between rurality and racial/gender identity. J.T. Roane, a professor of Black Geography at Rutgers University, describes ‘dark agoras’ as “insurgent Black working-class migrant formulation as constantly changing identities and social structures.”3 Following this idea, I look at how alternative social networks emerge and expand. Historically, communes get cornered into their insular separatist identities. In contrast, recent justice-based farms and food sovereignty movements, for example, many in the Hudson Valley, are based on the radical idea of creating a social infrastructure that cares for better food and climate systems amid systemic oppression.

"I trace the intersectionality between rurality and racial/gender identity. J.T. Roane describes ‘dark agoras’ as 'insurgent Black working-class migrant formulation as constantly changing identities and social structures.'"

- Stephanie Kyuyoung Lee

PS Borrowing from Tiago Saraiva's book Fascist Pigs,4 which connects the development of agricultural produce and animals to insurgent fascist transformations in Italy, Spain, and Germany, there's nothing new in Nazism; it's a reframing and streamlining of existing white supremacy ideas. Its agricultural ideology of ‘Blood and Soil’ operated a legal regime of ownership and property by centering the peasant as the main Nazi ideological figure as ‘new nobility’, and as landowners and agricultural producers as the ‘blood source’ of Aryan supremacy. So ownership and racial superiority are the basis for understanding the value of land and soil within Nazism. Following Cesaire and others,5 Nazism was the return of imperial and colonial violence to European soil. It brought back models of capitalist extraction into Europe and found redistributed property structures that in Austria shifted from aristocracy and clergy towards peasants from the Napoleonic Wars onwards. This came together with pre-modern concepts of profit that were introduced with subsequent still imperial taxation models, i.e. the Franciscan land tax edict, and allowed to accelerate industrialising agriculture for the Nazi war effort from this fertile ground.

KOOZ In early U.S. history, agriculture was a way to colonise and establish a new power. In the longer European history, agriculture has been a way to maintain an established power. So, farmers' identity and political role differed because their trajectories differed. How do your works deal with memory and identity and consider them evolving political entities?

PS Memory is crucial in my project because I'm interested in how subjugated or wilfully obliviated history informs the present. It's not something closed. It's an ongoing process that feeds into contemporary conflicts. With Trembling Worlds, I question the introduction of profit, the capitalist approach to agriculture, production for the war and post-war reconstruction, the European single market, and the globalised agro-business system, all the while looking at a town with a mere 200 inhabitants. Still, all these forces impact the current day from reading this small place. This back-and-forth of the micro-macro, the before-and-after and how these have shaped a radically different concept of agriculture and property, is a major departure point. This trajectory is not a simple causality but has been engineered precisely as a background and ongoing project characterising the status of our world, from which we can read the rise of new conservatism, and what Alberto Toscano calls ‘late fascism’:6 this global re-articulation of right-wing ideologies.

"I'm interested in how subjugated or wilfully obliviated history informs the present. It's not something closed. It's an ongoing process that feeds into contemporary conflicts."

- Philipp Sattler

SKL Narratives of memory and identity under coloniality are perennially written from a point of extraction and suffering, so I investigate the process of archiving and accumulating data to rethink the agency of the researcher. In R-words: Refusing Research, Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang question the academic gaze, where research that claims subaltern subjectivity may be complicit in reproducing Western forms of power. As a researcher, I must decide which forms of knowledge don't need to be documented for “research”. Such refusal is not a rejection of academia but a way to understand how to think of ethnographic knowledge as regenerative instead of extractive. For example, Hard Labor, Soft Space is an attempt to reimagine historical narratives from the perspective of active resistance in this way. Focusing on memory and identity is fundamental in the current academic crisis; academia is not a safe space, as evident from how current politics target Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives.

KOOZ Rural economies in Western societies are often linked to social and economic systems based on racial discrimination and patriarchy; financial means and legislations have historically favoured disparity and accumulation in land ownership. What are the top-down and bottom-up tools to dismantle such inegalitarian and unjust models, which are themselves often connected to exploitative labour practices? How might we build new agricultural, social, and economic infrastructures?

SKL In the U.S., top-down approaches have never served BIPOC farmers. Beyond the formative colonial land grabs, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has a long and consistent history of disproportionate loan offers for white farmers compared to BIPOC farmers and unfair practices towards the latter. For example, New Communities Inc. was the first community land trust and a Black farm cooperative that spanned 5000 acres. It was ultimately closed in the 80s through discriminatory loan practices and deed confiscation by the agency. If land grabs and dispossession are the basis of U.S. property laws, then how can we imagine top-down approaches? Government subsidies and practices would need to change fundamentally.

Regarding bottom-up tools, the Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust has been instrumental in shifting the farming conversation to a political level. They have created a digital grassroots land reparation map for land-back projects where BIPOC farmers looking for land can connect with land owners and vendors. Such grassroots projects help facilitate more than just agricultural infrastructures.

"Beyond the formative colonial land grabs, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has a long and consistent history of disproportionate loan offers for white farmers compared to BIPOC farmers and unfair practices towards the latter."

- Stephanie Kyuyoung Lee

PS During World War II, Austria promulgated agricultural loan system laws which benefited only those farmers who were part of a racial register — following criteria like farm size, blood purity, and hereditary patriarchal lineages. By changing the finance system, farmland was grabbed from Jewish peoples, small farmers, and those who ideologically were not part of those categories and was accumulated by big farms through foreclosures. This sophisticated and legal cheap long-term loan system that enabled land grabs lasted until 1999, with the termination of the law after the last loans had run their course. Once Austria entered the European Union and its Common Agricultural Policy, agriculture became dependent on a global market asking for cheap production, which only large ownerships can afford. It’s a top-down process that started here and scaled up to global agro-business.

Regarding bottom-up approaches, there are small structures, especially in rural alpine regions, which are border places where it is logistically impossible to scale up agriculture. They are areas characterised by multiple identities that don’t fit in the pure Germanic framework but often contest it. For example, the Slovene-speaking minority at the Slovenian-Austrian border organised the only militarised resistance against Nazism as a partisan movement within the territory of the Reich; they were forest workers, small farmers, and people excluded economically and ideologically from a system that benefited others. There are places of contestation and resistance still where there are small farming projects run by anarchist, feminist, and queer collectives questioning the nature of property, focusing on land-back, and dismantling patriarchal systems.

Hard Labor, Soft Space: Making of Radical Farms: “Vegetable crop display, Amache Agricultural Fair, September 11 and 12” Granada War Relocation Center. Photo: Joe McClelland, War Relocation Authority, 1943. Credit: Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration.

KOOZ You mentioned feminist and queer perspectives, which represent two alternatives to the patriarchal farming model and capitalism at large. Do these alternatives gather around commoning practices?

PS What is striking in these projects is their immense struggle to exist. Usually, they start from a single person who inherits a small farm or forest land and want to rethink how to practically deal with alternative models to private ownership and agriculture-as-business. However, the amount of legal trouble they get because for example they don't manage the forest but restore it is immense. So, they look for and often create support structures to share responsibilities. Sometimes even internationally to other anarchist farms and commune projects and networks. Or a former smallhold and site of Nazi atrocities, Peršmanhof, developing a seemingly local memory culture project about partisan resistance of Slovene-speaking minorities, connecting to the Zapatista movement. The internal system vehemently opposes these collectives, so seeking international support is necessary and offers a collective model against particularising capitalist modes of being.

KOOZ It is interesting how you also mentioned models of internationalism, which produce systems of care contrary to the closeness of nationalistic ideologies.

SKL I like this idea of crossing borders and solidarity, even hints at post-human solidarity amongst these collectives. It’s all about trying to regain a shared future of land-back to incentivise smallholder farmers and dismantle this capitalistic system of private ownership and food production. Scale is an obsession of mine. It's not just going from grassroots smallholder farms and scaling it up to a global system; it's about understanding the system in order to build tools by synthesising knowledge into something realistic.

PS Yes, it’s a praxis. These smallholder farmers and projects support each other, creating environments that benefit the ecosystem and diversity in food production. The stuff we discuss is typical in noncapitalist systems. Capitalism is not inevitable, and as Ursula K. Le Guin said in her acceptance speech to the National Book Foundation, it's like the divine right of kings: it can disappear. For example, looking at pre-modern times brings an imaginary evocative of a future of abundance. The Franciscan land tax edict also established an enormous cadastre mapping of the whole Austro-Hungarian empire — the Franciscan cadastre being based on land use and production. These maps are an incredible image of pre-modern agriculture and indicate the rich diversity of produce and landscapes. maps.arcanum.com collects all these hand-drawn maps, amounting to over 300,000 paper sheets measuring 30 by 40 centimetres. It’s an historical work that can help us think about and speculate about potential regenerative futures.

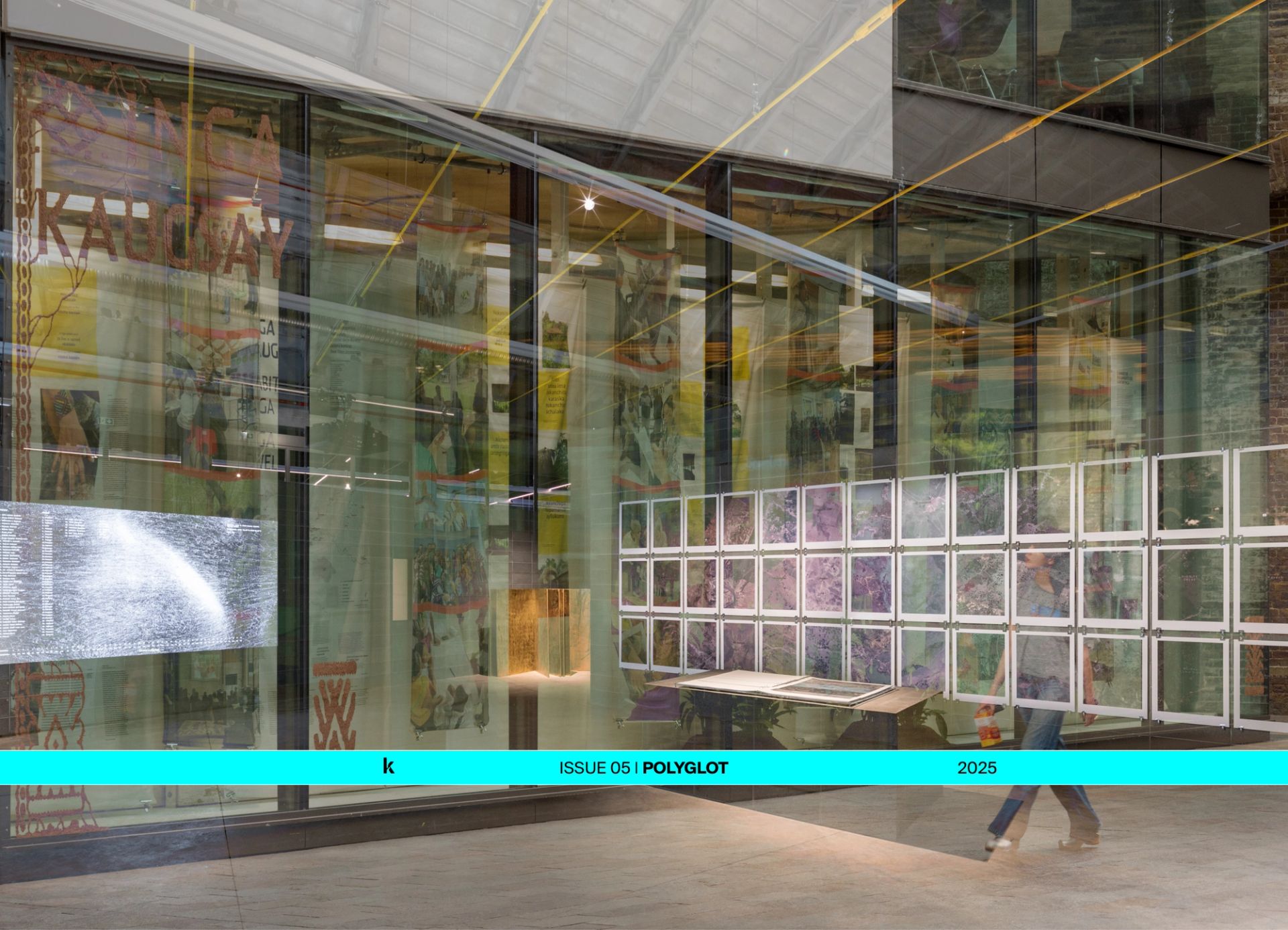

Trembling Worlds: Virtual assemblages of the ground, digital performance of the Aflenz Research Archive, 2022.

KOOZ Thanks for mentioning archives and mapping. What is your methodology regarding archive- and field-based investigation, considering the soil is an archive? I am very interested in how you collect data, build your archive, and use critical cartography and other mapping and interdisciplinary representation practices to describe different and complex mutating systems.

SKL Philipp, I was inspired by your article on investigative memorialisation and how you look at soil as a material and historical archive, the regenerative memorial, because my drawings are frequently an act of commemoration. They document the currency but are static and only sometimes represent how I collect information, which is informal and largely based on communal knowledge. I am sharing maps or drawings of each farm with the people there and then getting feedback; it's a process of accumulation. Consequently, the drawings constantly change because most smallholder farms are based on precarious ownership, like leases or loans: they often close and change the model of co-ownership or location. Because Black farmers own 0.32% of land in the U.S.,7 and other farmers of colour even less, land ownership can’t reflect how I map and record places. Updating all the changes is an accretion process, and I am considering alternative ways to show this exchange. I am looking at open-source shared digital maps. My concern around more general mapping is that it is historically such a core practice of colonisation. Consequently, the main issue becomes how to use mapping as a subversive act and tool for critical cartography.

"The main issue becomes how to use mapping as a subversive act and tool for critical cartography."

- Stephanie Kyuyoung Lee

KOOZ I agree; we need to formulate new mapping practices.

SKL Exactly. As an undergraduate, I studied Anthropology, and there's always a desire to return to those roots and develop a relationship between spatial work and visual ethnographies. In the recent exhibition I did at New York’s citygroup gallery and Verse Work/Shop, Hard Labor / Soft Space: The Making of Radical Farms, I coupled spatial drawings — maps, diagrams, and timelines — with a short film that documented a dinner with the collaborating BIPOC farmers and activists. The “dinner party” goes back to the historical origins of symposiums: we shared a meal, sang, and discussed radical cooperative work, farming as marginalised identities, and the colonial implications of utopia, which comes from a Western approach to dreams that evades how to achieve them. The film visualises a decolonial perspective on how agriculture, spatial justice, land, and labour are inherently intertwined.

"There is always this question of the specificity of the context where archeologists, by digging, make a choice impacting interpretation. The documentation of the process becomes part of the knowledge accumulated around the excavated objects."

- Philipp Sattler

PS I find your idea of collectivity beautiful, as a refusal of maps’ reductivity, and the need for all the elements, for a constant coming together without losing their complexity. It connects to investigative memorialisation, a term coined by my colleague and artist Milica Tomić, who is developing a memorial project on the site I was referring to and on which we also work together, and with a wide number of local and international contributors. This approach implies a sensitivity to context, different layers and scales of soil and history that collapse into the site, and comes from concepts of interpretive archeology developed from the 80s onwards, as well as Milica’s work with Grupa Spomenik around the Srebrenica Genocide. For interpretative archaeology , there is always this question of the specificity of the context where archeologists, by digging, make a choice impacting interpretation. So, the documentation of the process becomes part of the knowledge accumulated around the excavated objects.

Assembling knowledge is a very material and documentary practice. It must always bring together the multiplicity described by Stephanie to create and build an ongoing discourse that makes it a public matter of concern. In this sense, encountering the soil for us is important as it speaks to both the past and present moment. The questions of property, agriculture, and ecology are central as they can be read from the soil layers that contain things that are discovered through excavation and archeo-botanic floatation, as well as what grows out of and is changed in the soil by containing, or as we frame it, unwillingly archiving artefacts and subjugated histories that connect past and present. It's all about assembling, documenting, interpreting and learning from these objects and from people like Franz Trampusch. He was a kid living on a farm within the camp area we work on and he kept the memory alive through his private archive, initiatives he founded and his political career. It's a question of legacy, of local people's initiatives to save documents and knowledge that otherwise would disappear, actively or by neglect. Assembling means being aware of these legacies, working collectively, and interpreting them in their context. Accumulating knowledge into a process is something that can never be finished.

KOOZ I have always been interested in agriculture because food production can tackle ecological and economic issues and societal models. Still, another relevant aspect is its pedagogical value: it might sound like a joke, but today, I wouldn’t be surprised if a city person believes bagged apples are produced in a factory. Does your research address the educational value of agriculture?

SKL As you point out, there's a removal from agricultural production and there’s also a long-standing binary between rurality and the city where the countryside serves as a unidirectional extractive supply for the city. But it’s more nuanced. These farms and networks are not trying to be reified simply as spaces in the countryside; they participate and sustain an active relationship with the city. My current research and courses reinterprets this connectivity and highlights the relational aspect between land, labour, race, and agriculture, which are all part of this oppressive system that alienates food production. Sweet Freedom Farm, Gentle Time Farm, and Mumbet’s Freedom Farm, for example, are more than typical smallholder farms. These farms operate as a space for education, experimentation, and relearning the earth, as places where the soil is a right for everyone. They are schools to learn and experimentation labs to think about cultivating collectively.

"These farms operate as a space for education, experimentation, and relearning the earth, as places where the soil is a right for everyone. They are schools to learn and experimentation labs to think about cultivating collectively."

- Stephanie Kyuyoung Lee

PS I'm not that directly involved with agricultural producers in my teaching; my project deals with these issues slightly differently. What I bring to architectural education is trying to understand what processes are shaping the landscape, like how legal and property questions impact agriculture practices, the formation of rural space versus the city, the development of peri-urban areas, and how the sprawl of towns extends into former agricultural land. But also what landscape tells about histories of violence, learning from more-than-human perspectives, and the false dichotomy of urban and rural space. My project addresses memory and the memorial culture of a population that doesn’t want to talk about the history of Nazism or the legacies of the camp in their area. Nonetheless, there are efforts, for example in Aflenz an der Sulm, led by the current mayor, who was himself educated by Franz Trampusch, to keep the obscured fascist histories alive and bring it to schools and the public, through guided tours and events that discuss these issues. This includes local teachers and volunteers that develop educational initiatives to connect the questions that come out of this space with contemporary issues of migration, segregation, and cultural changes, which counters right-wing attempts to co-opt these issues for their own agendas. There’s always someone asking, "What does this have to do with me?" but as soon as you look at the camp, you see 20 different nationalities: French, Chinese, Czech, Greek, Soviet, Yugoslavian, Belgian — the list goes on — all people from various geographies that connect to visitors and their own varied cultural backgrounds. In turn, this opens different historical trajectories and legacies of power informing this discourse, which has a solid political impact on education in schools, whilst being constantly under threat to be diminished. It’s important but increasingly difficult work.

KOOZ I have a final question. What are your work’s operative and reparative implications for decolonising farmland and imagining other societal systems?

SKL The questions I pursue include the following: "What does a land-back project look like?", "What are the examples of past and present land stewardship rooted in reparation and liberation, and what are their tools?", “How can we think about the relationality between activist projects and imagine them at different scales?” Each of these farms has different modes of experimentation, even if they all have a justice-based approach to farming. These experiments involve various modes of living at the intersection of queer identities, Black liberation, or Asian American land sovereignty, and they are intentional about this collectiveness. Jalal Saber from Sweet Freedom Farm always reminds my students that they operate as more than just a farm: their activity is an attempt to restructure injustices through an abolitionist approach to farming. In collaboration with the Sing Sing Family Collective, they provide fresh produce to families and loved ones of individuals who are currently incarcerated. Through the work of Sweet Freedom Farm, we understand how a farm can become both a model for educational space and a tool for prison abolition in New York State. Radical agriculture is not about an alternative infrastructure in the existing system to decolonise the farmland; it’s a new world-making approach.

"Radical agriculture is not about an alternative infrastructure in the existing system to decolonise the farmland; it’s a new world-making approach."

- Stephanie Kyuyoung Lee

PS My project aims to respond to a substantial unresolved question, that is, understanding what Nazism was and did to the country. It took the Austrian state until 1993 to acknowledge that they had been an active part of Nazism and not only its victim. It is an unresolved denazification process that happened on an official level and never touched the political system's core. So the larger project of a memorial for the labour and concentration camp Aflenz an der Sulm — from which Trembling Worlds developed while also having its own dimensions — brings the idea of a memorial, not as an ossified memory of what happened but rather as a way to think about the connections, ideas, and knowledges that result in and from that memory. Crucial to this project were our exhibitions and conferences, as well as the book I am developing together with Milica Tomić and Dubravka Sekulić, that posits these questions as a public matter. All these things resonate in a project that doesn't close down on local specificity but deals with more significant questions of contemporary society and its histories of fascism and capitalism in different conflicts — from Brenna Bhandar’s Racial Regimes of Ownership,8 to Alfredo González-Ruibal’s archaeological work on the Spanish Civil War or around the role of Palestinian women as workers in British Mandate excavations by Dima Srouji. The project is a form of solidarity through bringing together various practices, precisely like this conversation. This confluence of practices and ideas is something to learn from because it shows alternative systems and approaches and that different places can learn from each other by starting to dismantle the system.

Trembling Worlds: Partisan monument, Peršmanhof, Carinthia, artist Marjan Matijević. The only partisan monument in Austria depicting a woman bearing arms. Unveiled 1948 in Völkermarkt/Velikovac, destroyed 1953, reassembled and erected on Peršmanhof 1983.

Bios

Stephanie Kyuyoung Lee is the founder of the Office of Human Resources, a critical design studio that explores the intersection of spatial, racial, and material politics as a liberatory practice. Her current project builds a comparative genealogy from early communes to social justice-based farms located throughout New York. As the Strauch Early Career Fellow at Cornell University, Lee’s courses focus on utopian agrarian projects, botanical histories, and rural commons as topics of design research. Previously, she was awarded the inaugural Architecture Fellowship at Bard College. She has exhibited her work at Haus der Architektur in Graz, Austria, and citygroup gallery in New York City. Her writings and interviews have been published in KoozArch, The Funambulist, PLAT, and Archifutures (dpr-barcelona, 2020).

Philipp Sattler (1990, Austria) is a researcher, artist, architect, and educator with a background in Architecture, Economics, as well as English and American Studies. He is an Assistant Professor at IZK - Institute for Contemporary Art, Faculty of Architecture, Graz University of Technology, and PhD student at the Royal College of Art (RCA), School of Architecture, London. He is a founding member of Das Gesellschaftliche Ding, who operated and curated the exhibiting space "Annenstrasse 53," in Graz, Austria. His transdisciplinary work concerns the material and conceptual conditions, spatial manifestations, and ecological devastations of agriculture, mining, and property and the relationships between the rural and the urban. He currently works on environmental and architectural histories of violence along the Austrian-Slovenian border in several projects: Trembling Worlds: Agricultural Morphologies and the Regimes of Space-making of the Austrian Hinterlands (working title); the Aflenz Memorial Project, and How Does One Get To Own A Mountain?!.

Valerio Franzone is Managing Editor at KoozArch. He is a Ph.D. architect (IUAV Venezia) and the director of the architectural design and research studio OCHAP | Office for Cohabitation Processes. OCHAP focuses on the built environment and the relationships between natural and artificial systems, investigating architecture’s role, limits, and potential to explore possible cohabitation typologies and strategies at multiple scales. He has been a founding partner of 2A+P and 2A+P Architettura. His projects have been awarded in international competitions and shown in several exhibitions, such as the International Architecture Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia. His projects and texts appear in magazines like Domus, Abitare, Volume, and AD Architectural Design.

Notes

1 Timothy Miller, The Quest for Utopia in Twentieth-Century America (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1998).

2 Dolores Hayden, Seven American Utopias: The Architecture of Communitarian Socialism, 1790–1975 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1976).

3 J.T. Roane, Dark Agoras: Insurgent Black Social Life and the Politics of Place (New York: New York University Press, 2023).

4 Tiago Saraiva, Fascist Pigs: Technoscientific Organisms and the History of Fascism, Inside Technology (Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England: The MIT Press, 2018).

5 Césaire, Aimé, Discourse on Colonialism (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 2000).

6 Toscano, Alberto. Late Fascism: Race, Capitalism and the Politics of Crisis (London, UK: Verso Press, 2023).

7 (online)

8 Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership, Global and Insurgent Legalities (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018).